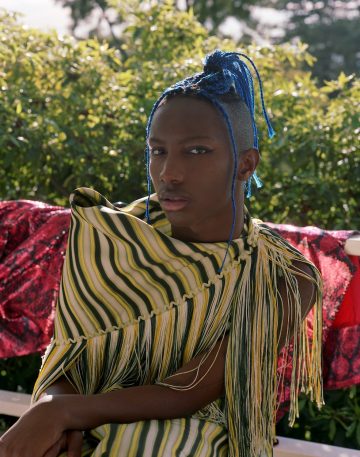

#EMPATHIE: MOORE KISMET

Words by Damien Cummings

How was your first day in Germany, I would like to ask you. What happened on that day?

And the days after that, when you came to Germany in 1965. I have often asked myself how your time here in Germany began and what you experienced. Particularly the time before you came to Mannheim. Those two years you spent alone in Hamburg. I haven’t had the chance to ask you how it was when you were traveling alone for the first time, far away from your family. Not even my parents could help me illuminate the memories that remain in the dark.

I want to see what you saw and walk in the same shoes you walked in. From the first meters in Hamburg’s central station to the ones that brought you to the workers’ shelters in Wilhelmsburg. I want to understand what this arrival in Hamburg triggered in you. What were the first things you did there? Did you get a fish roll you knew so well from your home in Balikesir? Only to find out that the fish was pickled and not grilled, as you had expected it to be. What was your first impression? A first impression that can often be the most important and the most directional. I want to immerse myself into your emotional state on the day you arrived, and even beyond that, I want to understand the consequences not just for you, but later, for me too.

I know exactly three things about your stay in Hamburg.

You lived with five other contract workers in a two-room apartment with a small eat-in kitchen; you worked as a peat cutter in Altona; and it took you three days to travel the Balkan Route from Istanbul to Hamburg. You traveled alone – what souvenirs from your home did you bring in your suitcase? You most certainly packed your extravagant shirts with the extra-wide collars (which often caused you to be picked on back in your village) as well as your flasks with their strong, oily scents. But what else? I doubt that you brought presents or pictures of your family.

You were never a guy of great gestures. I would still like to know how your farewell was when you started your endless Balkan journey across many of Europe’s historical cities in the early spring of 1965. It must have felt like a departure into an unknown world filled with hope. A new chance and escape out of the crisis-ridden Turkey. Leaving the farm work behind and entering newfound prosperity. The slow screeching halt, the sluggish acceleration of the train and even the shrill whistles of the conductors – it must have sounded like hope in your ears. However, the fact that you left your family behind surely caused some turmoil.

Chasing the promises of others, many young men moved to Germany without their families, even before you. After the overwhelmingly positive response of the first wave, showcasing pictures in front of German cars and envelopes with money, you followed suit in the second wave. In retrospect, we know better. Most of the stories turned out to be beautifications of the real world.

Nowadays, when arriving in new countries I can use my English skills in airports and train stations to find my footing. But without it I would be completely lost. In your time, there was little to nothing in the way of preparation for a contract worker embarking on a new life in Germany. Germany was not interested in your culture or family; they wanted you for your strong arms. Your stay was supposed to be temporary, not eternal. And just like that, alone, you arrived in Germany without any knowledge about their culture and their language.

My brother often described you as a loner, a man of very few words.

Presumably you didn’t let the stress and cluelessness show at all and jumped off the train with the many other young workers and silently made your way through the station. Asking for help was not your style.

Did the ‘promised land’ meet your expectations on arrival? Or had you hoped for something else? You had probably expected a more joyful reception. But then again, maybe you were happy about the lack of a reception committee. You never liked festivals, even the big traditional family farewells with their drums and fanfares were kept as infrequent as possible or, ideally, avoided all together.

I remember very clearly a certain scene when we said goodbye to you, my grandmother and my brother at the end of my first school year. My father had to work for a few more days and you had decided that the three of you would leave for the summer vacations in Turkey and that we would follow later. It was a big deal for my parents to let my eleven-year-old brother travel with you. While the entire neighborhood gathered around the old Mercedes in the parking lot of our apartment complex for a barbecue and goodbyes, you stayed in your room until it was time to leave. Even the suitcases were loaded into the boot of the old pastel green limousine single handedly by my dad. When everyone was ready, you swung behind the wheel with a quick goodbye and were already around the corner before we could even pour the water behind the car. Even our custom of pouring water behind travelers didn’t sit well with you, although all we wanted to wish for was your journey to flow like water. I remember this situation so clearly as your peculiar behaviour left everybody behind feeling perplexed. Years later the story allowed a lot of laughter. Was your farewell in 1965 as short lived? You kept everybody around you at arm’s length. Were you afraid of hurting or disappointing others?

The fact that no one greeted you at the station must have been convenient for you, since you liked to keep your distance. But still, you must have been a little disappointed. You were not gifted a moped, which the one millionth contract worker had received from the Federal Republic of Germany as an arrival gift at the end of the 50s. Nor were you greeted with a jubilant reception from the masses or a bouquet of flowers. You were merely labeled as one of the many millions of other workers who poured into the economic miracle country every day to rebuild the country. No rapprochement, no welcome, no handshake. In Turkey you had your family, but no work. Here you had work, but the price was loneliness. A simple temporary exchange. Only you can know the answer to the question of what was better for you.

The way I got to know you, you probably followed your own nose anyway and made your way to the best of your knowledge and conscience towards Wilhelmsburg and your designated rental barracks. Years later, in a conversation with my brother, to whom you were most devoted in the family, I learned of your living situation. You only ever mentioned the barracks to my brother fleetingly, ensuring not too much information is revealed. Who were your roommates? Did you drink after-work beers, you and the nameless, once you finished pricking the peat? Did you mix up your socks, the six of you living in 30sqm? I hope you managed to laugh from time to time.

I’ll probably never hear the stories about your first day at work either.

As a child, I once had a vague experience with peat myself. We visited a swamp area with school at a former old Rhine tributary . In the early 20th century this area was used to grow peat. Our guide showed us the workers gear and outfits, explaining how the peat was pricked. Usually there were three groups with three different tasks. Firstly, the first 30 cm of soil layers had to be removed. This exposed a one to two meter thick peat layer. During the night time, workers filled the deduction graves with pressurised water. Therefore, the so called water man had to get up 2 hours early, often around 3 am.

The detourer cut the peat into even blocks in the size of a brick. Thereon, the engraver cut the pieces below and to the side. They used a peat knife and the peek of the blade was the precise width the pleat had to be. The wages and selling price were based on every 1000 peat pieces. You and your fellow flat mates probably worked as the water man, tormentingly dragging yourself out of bed at 3 am, wearing rubber dungarees in the ditch. Thinking about it I realise how privileged I am in life. Together you cut and lifted the heavy peat briquettes. The more the better. I can hardly imagine how you were standing there in the velvety sediment, lifting one after the other during the Hamburg rain drizzle. I see you in my mind’s eye, standing knee-deep in this bog, a light steam rising from you, your forehead shining damply, whether it’s your sweat or the drizzle, one can’t know, but you plod on, everyone plods on, because every stitch brings money. Every stitch is a reason why you left Turkey for Germany.

Yet you remained silent about it. I wonder, did you gladly come to Germany? Or do you regret your decision?

It was not only you that kept your story to yourself, but countless other contract workers did so, too. This narrative is strikingly common in my circle of friends. There remains a collective silence among the first generation, as if the time between arrival and family reunification had been left out. Maybe you would all like to erase this time period from your memory? What happened during this time that you are keeping silent about it? I assume you remain silent as your expectations turned into disappointments. And in retrospect, that you are ashamed to have harbored such stock naïve expectations at all, back then, in your early 20’s. Many contract workers realized at the moment of arrival that Germany was not the financial paradise, the golden ticket to wealth, but hard, physical work in a social isolation. You found yourselves in a “gated community” in which the fences were not put up by the people residing there, but by the people outside. You were crammed into the smallest of spaces by society with your peers. You were among yourselves and that’s how it was supposed to be. No exchange and or touchpoint with the German community. You were supposed to work and ideally leave upon completion rather than putting down your roots.

I can see what the isolation has done to you. Even though you have always been a loner, these two years in Hamburg without family must have left their marks. I do not know if you would have taken this leap of faith to leave for Germany had you known the circumstances and consequences.

Yet you have opened a door for my brother and myself. I am glad you took the brave step to leave for Germany. Like many others, you could have just thrown in the towel, but you never did – you stuck it out until the end. For that, I am eternally grateful and proud – yet every time I think of you, I wish you could have opened up to us. We could have helped you if you had shared your feelings rather than isolating yourself. I would have liked to learn from your experiences – to understand you and us better. If one day you want to talk, I am here for you.