TO WATCH: “ONE TO ONE” BY KEVIN MACDONALD

This documentary feels like reliving a time through the eyes of Ono and Lennon.

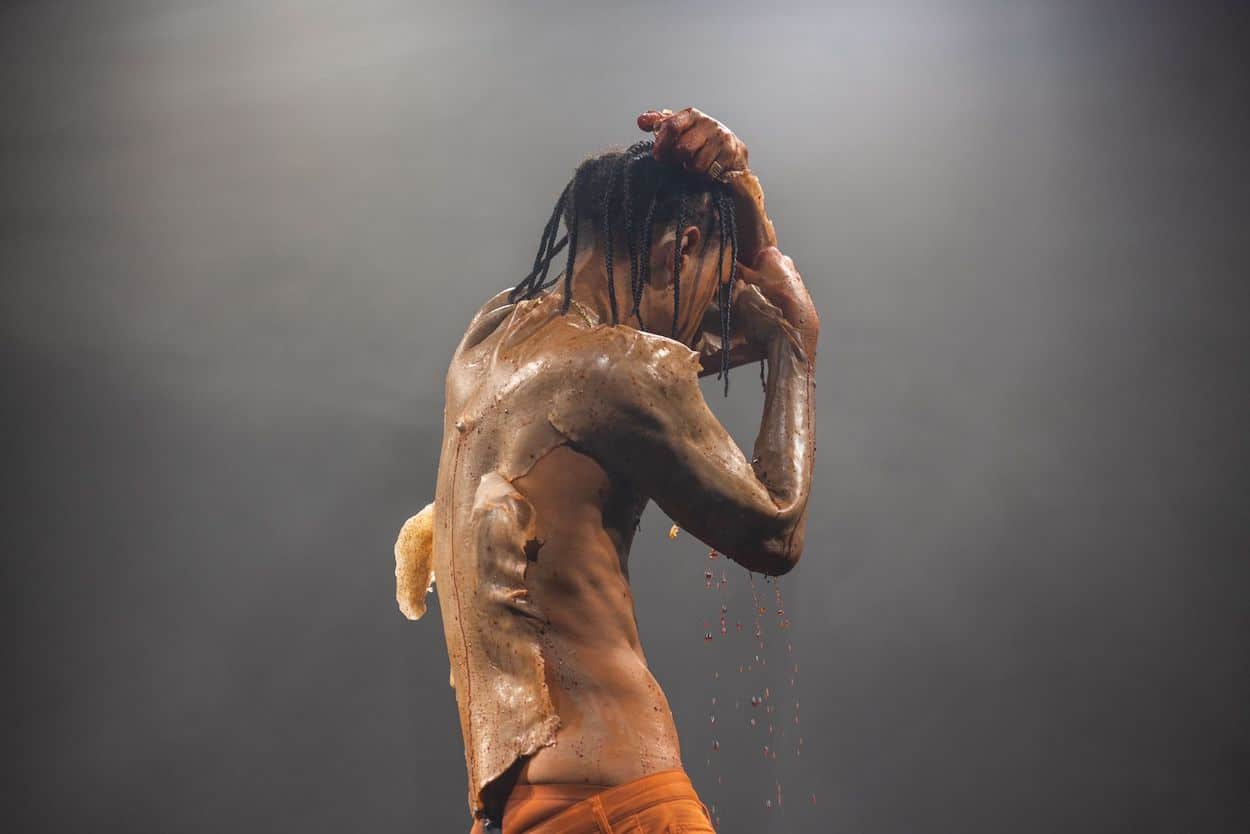

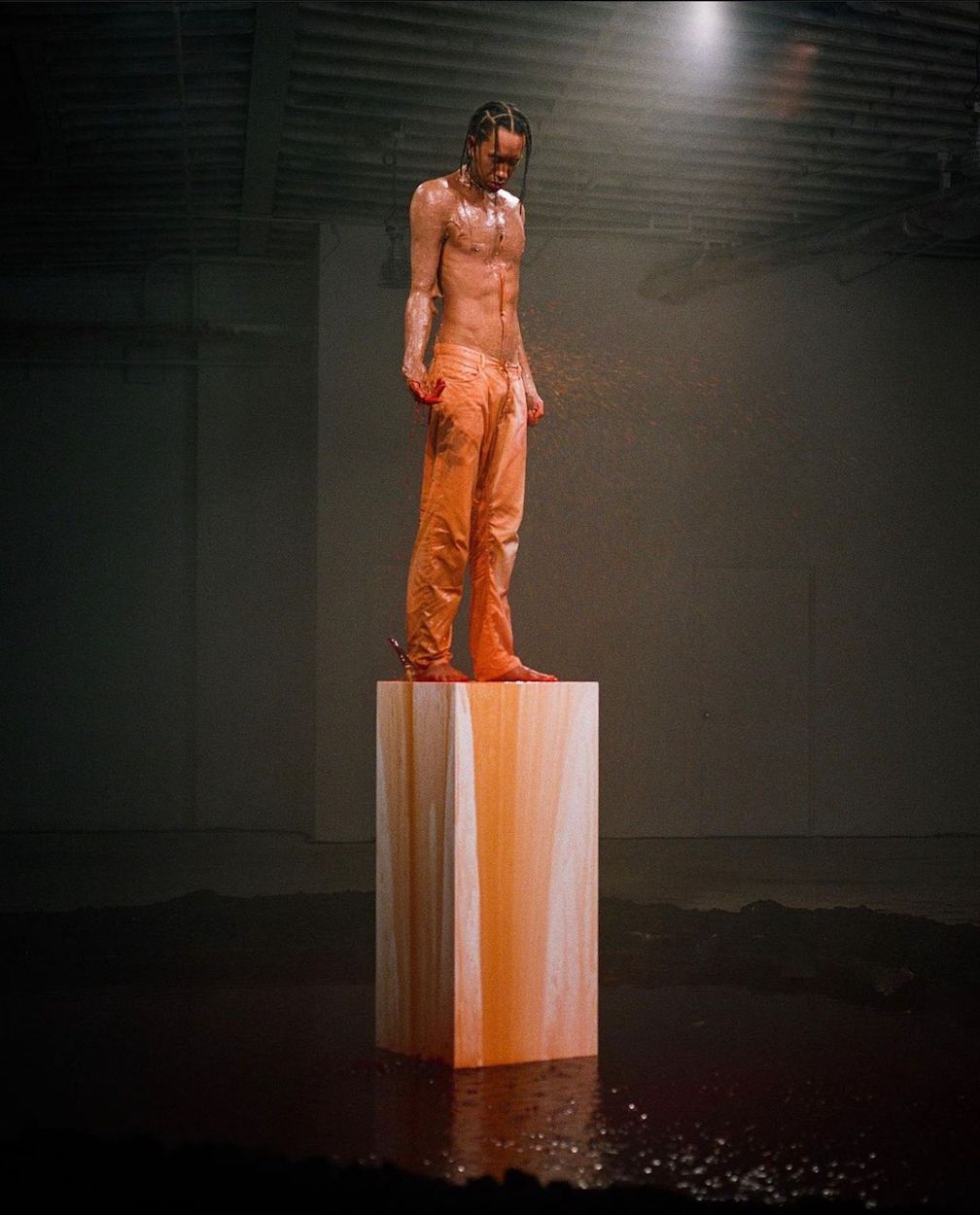

Miles Greenberg leads us through movement into the world of the extreme and let us ourselves experience it in the same breath.

The New York-based artist and sculptor creates haunting images in which the body itself becomes the sculptural material of the installation and surrenders to it, sometimes over several hours, finding himself in states of exception or gazing into the eyes of fears and phobia.

Numéro Berlin talked to Miles about his latest performance “Fountain I”.

It’s the use of the body as a material, as a subject and as an object simultaneously. When I make performance, I think that I operate very similarly to how a sculptor, or a painter does. Incidentally, now, I am a sculptor, and I don’t feel any different. I work in performance art in the way that I would work in anything else.

I find it very difficult when people call me a performer. I think that’s very different because a performer is somebody who executes an idea, but they are not necessarily the author of it, or the motor behind it. I’m the creative motor behind everything I do.

Performance art was a blessing to me because I immediately had access to it. It was something that I kind of fell into as a means of creating because I could do it without an academic background, or much of anything; I could do it without a studio space or materials or really much knowhow. I just had to know myself and my body. I found ways to place it in tension in the way that all artists place their material in tension. I always dreamed about being a sculptor and so I’m actually very excited to be now approaching sculpture from the education that I kind of forged for myself – from within the realm of working with the body. It’s the same way I taught myself how to make video, from my self-education in the body. This sort of interplay of media is much broader than what you can say is like a sort of executive job like ‘performer’ or an ‘interpreter.’ It’s a whole system of creation.

My use of my own body is something that’s somewhat incidental. It isn’t because I consider myself an artwork or something. I have a very sort of big separation between what I would consider my body on stage and my body as a civilian. The solo works are just very immediate, and I have control over them, and I can also take responsibility over them, without the logistics and implications of employing someone else’s body. And I can push myself further than I would really feel comfortable pushing somebody else. I protect my performers and I protect my audience. It’s also worth noting that when I do performances, I always do the first couple of them myself. I personally perform and test everything on myself before I would ever put somebody in these positions, I think that’s crucial to avoiding unintended violence. I’m starting to recognize it as a distinctly Gen Z, queer, Black trait, having this profound relationship to violence that allows one to know not to replicate. I and my generation, people like me, know that it is possible to talk about violence and to illustrate violence without recreating or perpetuating it.

Absolutely. Like a vaccine, we use a dead virus to build antibodies and create immunity, not a living one. I think it’s very important, in art, to not reduce living human beings to a symbol. I have a lot of respect for life. That’s just the sensibility I think we have arrived at in 2022.

“I have to tell myself things like ‘I don’t get married. I don’t have kids. I don’t do anything. Nothing in the future. Nothing ever happens in the future but this. I never see anybody ever again. That’s it,’ you know?”

That was easy! It was a phobia, and it still is. But phobias are really fascinating. We’ve all developed phobias I think through maybe our genealogies or, you know, it’s all survival instinct, right? It’s something meant to protect us, like our instinct to reproduce. We can override almost all of these instincts and I think that we get somewhere really magical when we do. Fear was something that I wanted to explore and tease. And then you can see where this brings you, like a proverbial door that sort of slams in your face every time you approach it. You can’t really touch it or turn the handle. But what happens if you do and see what’s behind it?

If I see a huge moth with like eye patterns, I still be really uncomfortable, but I can sort of sit with that. For me, it’s a thing that I love to do with my performances, taking an extreme emotion like fear, love, sadness, heartbreak, ecstasy or whatever, and sit with it and see what happens. These are emotions that typically live in our bodies, always with very tangible, physiological reactions, through hormones and neurotransmitters like cortisol or dopamine.

Totally. But it’s physical, it’s chemical, it’s scientifically verifiable. Our body has very natural cycles to ensure nothing gets too out of hand. What happens when you take that ten minute or 20 minute or 30 minute cycle and you stretch it over like five or seven or 24 hours or even multiple days? Like what happens when you’re bored for three days? What happens when you’re terrified for 7 hours? Can you have an orgasm for a week? You don’t stay terrified and you don’t stay bored. What happens when you’re exhausted for 24 hours? What happens when you’re exhausted for seven days or in pain. Heartbroken, for however long. You just can’t, so something else happens and it’s beyond your control. So I’m kind of interested in those little things that happen beyond our control, they tell us a hell of a lot about who we are.

Performances, to me, are always like a demonstration. It’s something that I hope that people can do themselves as well, maybe not through the same exact means, but at least it shows a case study – my work is like a petri dish. You can see the organism of an emotion or an idea growing under optimal, clear conditions, so you can study it a little bit better, understand how it behaves. I don’t think of these exercises as it comes to an end.

I don’t think of myself as a very extreme person, but who knows, maybe I am.

I grew up on video games and I loved playing games like World of Warcraft, Skyrim, Minecraft, I played through every Pokémon game – always games that had expansive, seemingly endless open worlds. There always was an end of the world, though, there was an edge. Sometimes, if the internet cut out, a part of the map wouldn’t load properly and you would just fall off the edge of the planet. I remember when this would happen, and I could freely navigate all the parts that the game developers didn’t want you to see. I could wander down all the way through the crust of this fantasy earth I was so invested and until I was freefalling into infinity. In a way, that’s kind of what I’m trying to do with my work. Triggering these glitches and seeing what lies beyond.

Well, exactly. That’s what I’m saying. It was extremely difficult when that happened, but it was part of it. It had to be, because at that point I had gone so far past my limit, this was exactly what I was looking for. I actually don’t remember most of it, but you can see my face in the playback. You can see what’s happening. I’m going totally to other places, and it’s not all bad.

“I and my generation, people like me, know that it is possible to talk about violence and to illustrate violence without recreating or perpetuating it.”

I mean to do that, I try to stay present as much as possible through the process so that the performance is genuine. I try to stay absolutely in the moment so that I’m not drifting off and going elsewhere. I need the experiment that I’m conducting to be as effective as possible. Because if I’m thinking about what I had for lunch or what I’m going to have for dinner (probably nothing), then there’s no point. And I’ve wasted everybody’s time, including my own. The only way to go to behind the door is to do your best to stay in the here and now. Otherwise, you’re not going to go. It’s that simple.

Basically. But what I should never do is think about time. Inevitably it’s going to happen, no matter what. I mean, the grandest of masters is going to eventually wonder ‘when the fuck am I done?’ I go there when I’m performing, totally. Everybody goes there. Whenever I catch myself thinking about time, I have to tell myself that I need to be comfortable in whatever situation I’m in and whatever I’m doing for literally the rest of my life. That’s extreme. But as soon as you can resolve that this may well be the end of your life, this is it, you’re going to die here on this conveyor belt, and you make peace with that, then you’re there, then you’re present, then you’re good. I have to tell myself things like ‘I don’t get married. I don’t have kids. I don’t do anything. Nothing in the future. Nothing ever happens in the future but this. I never see anybody ever again. That’s it,’ you know? And then five hours is a lot shorter than forever!

I have obsessive compulsive disorder and panic disorder. So I have severe panic attacks, since I was a kid. It’s a thing that just happens in my body where suddenly, I just physically shut down and on a physiological level, my body tells me without any reason ‘that this is the end of your life.’ But it never happens when I’m performing.

Yeah, it’s like taking control of it, putting everything on manual. I mean, I still feel very much at the beginning of something. I’ll let you know when I find out.

I think that heartbreak doesn’t have to do with love all the time, you know? I think your heart can break without it being tied to romantic love necessarily.

Contrary to popular belief, it’s not about an ex or a breakup or anything like that. I think I was in a period where I was just experiencing a lot of transitions and a lot of changes and a lot of these repeated, intense emotional landscapes and panic attacks, moments of disappointments, things that felt so dramatic in a way that I knew I needed to have some humor about it. My grandmother passed away the day after this performance, and we all knew she was nearing the end leading up to it. I drove up to Ottawa overnight the following day to spend her last day with her and my mom. She had an iconic sense of humor, I think this piece was very tied to her.

I was really inspired by Björk and Sjón who wrote these lyrics in the song Bachelorette that go, ‘I’m a fountain of blood in the shape of a girl,’ which Björk herself describes as being a kind of darkly humorous hyperbole of over-feeling. I thought of illustrating that moment at the end of a movie, like in tragedy where it’s that overhead shot in the rain, and somebody is dying and bleeding out in somebody’s arms, and the person screams ‘NOOO’ up to God. That was what I wanted to do. But, like, what if that shot lasted 7 hours?

In a way, it was kind of a way to poke fun at myself, while simultaneously paying tribute to the emotion, as a means of sorting some shit out.

“I actually really wish somebody threw a coin in and made a wish.”

I wanted to create this situation, this pump and just be this constant cycling fountain of blood. This spring, this drama, just to sit with that apocalyptic feeling that I had until it ran dry. I worked with these prosthetics to kind of really melt the tubes of the apparatus into my body and almost make it a little bit more realistic. But by the end, these silicone things, which are not made to last 7 hours, completely disintegrated.

I went somewhere with this piece where it was ultimately very happy and peaceful. I wanted to make sure it was bloody, obviously, but it wasn’t grotesque. That it was visceral, but also that there had to be an amount of blood in it that was so exaggerated. It was so hyperbolic. That amount of blood could never possibly be contained inside of one human body. It was this expansive gesture that went beyond the real and into the surreal. I love the surreal and the absurd. But this also wasn’t theatre to me, it was close to life.

I wanted to expand beyond my own body. It was like a massive blood transfusion with New York. I basically wanted my circulatory system to expand beyond my body into a bigger space. And that was sort of what it felt like, it was like literally just extending my arteries into a mechanism that was huge so that I could feel like I was inhabiting somehow. Like expanding the size of my body.

Yes and I actually really wish somebody threw a coin in and made a wish.

This documentary feels like reliving a time through the eyes of Ono and Lennon.

On being brave: Numéro Berlin spoke with Little Simz about her freshly released sixth…

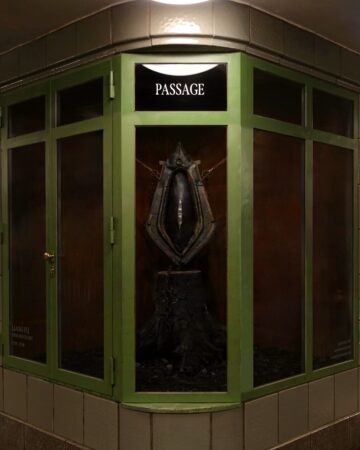

With his latest installation "SPINE BOUNDARY" at Hermannplatz, Berlin, Chinese born Artist…