IN CONVERSATION WITH LITTLE SIMZ

On being brave: Numéro Berlin spoke with Little Simz about her freshly released sixth…

Artist Alexander Wertheim, explores alternative perspectives in art. He delves into his transition from music to painting, defining art as a struggle between structure and chaos. We talked to Alexander about his art, how he found his way to it, and what criticism often accompanies it.

I am not sure whether I can recognize or define something as art but I think that an expression may become art if it shows an alternative perspective on the world.

I think good art is what stays in your mind.

“Mistakes or coincidences might look more interesting than what we intend or plan. Owning one’s incompetences may be helpful in the creation of art, similar to how it’s charming to speak with an accent.”

One three-dimensional thing that comes to mind is an installation of paper streamers that I did for a group show with my classmates in Berlin. I designed the streamers in several striped color rhythms and decorated the gallery’s ceiling. Also a few years back, I did the stage design for a theatre play consisting of window display articles such as fake cherry blossom trees. Besides that I never really sculpted myself… My father and I are in a regular artistic exchange.

I was drumming throughout my childhood, coping with my hyperactive disposition. As a teenager I spent my afternoons composing music and playing in bands. What struck me about painting is that nobody can watch you at work. So I went to Berlin to become an artist.

During my 8 years of studying, I experimented with very different ideas. For instance I was painting in a photorealistic style for a couple of years. During the time I was studying in New York, I was painting pillow cases and table cloths. In my last semester at University, I decided that I wanted to do something different and started to paint lines in different colors on white canvases.

My paintings depict the clash of horizontal and vertical entities. They try to construct a logic within the chaos of decision making. They show the struggle of a structure against its own disintegration.

For the show at Schlachter 151, I developed a new method of filling my canvases. On the bigger works I figured that there is a certain distance between the strokes that is just wide enough: not too crowded, not too blank. I transferred that grid matrix onto all the other paintings, meaning that the smaller the canvas, the fewer the painted strokes. Also, all the colors of the show derive from that big painting in the first room. Basically the whole exhibition consists of fragments of that starting point. Composition-wise, I was looking for a good balance between non-colors, pastel colors, primary colors and black. I wanted to make a harmonious, pretty exhibition.

With the new method of planning the number of strokes per canvas, I don’t have to make that decision anymore. The painting is finished after the strokes have been sprayed.

I often hear that what I do has been painted thousands of times… show me.

I can only speak for myself and I don’t work for experts blessings. I want everyone to like my paintings.

I think everything is quite perfect in the Berlin art scene. I just don’t think it is my place.

I much respect the interest of my colleagues in the digital space. My work though is about the real world, the human body, and interactions between those two entities. To me, a blank canvas is artificial enough. When I’m traveling, I use the drawing tool on my phone to capture ideas. I realized how tempting it is to withdraw actions. To me, one advantage of the digital is its ability to simulate: just like Notes may simulate a composition for me. But I am drawn to the un-erasable and factual. I work with the amount of risk that it takes to leave a physical trace. It excites me to interact with my environment physically, just like drumming does.

On being brave: Numéro Berlin spoke with Little Simz about her freshly released sixth…

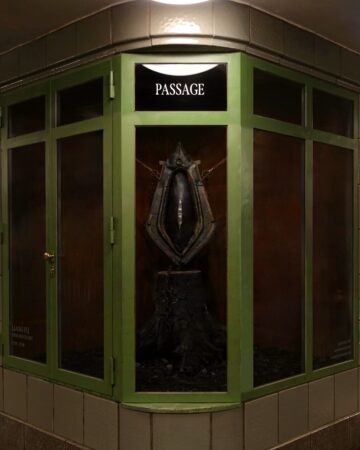

With his latest installation "SPINE BOUNDARY" at Hermannplatz, Berlin, Chinese born Artist…

Once a challenger brand in the automotive world, CUPRA has steadily entered a new era, one…

Interview by Chiara Anzivino