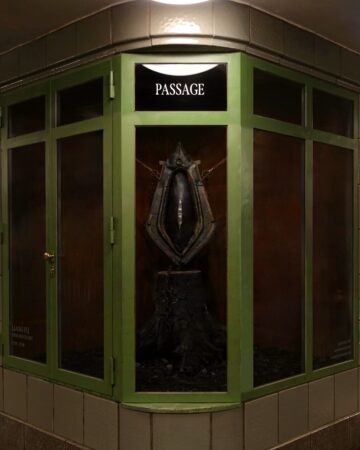

“SPINE BOUNDARY”: IN CONVERSATION WITH LIANG FU (FEAT. PASSAGE)

With his latest installation "SPINE BOUNDARY" at Hermannplatz, Berlin, Chinese born Artist…

If, like me, you’re a techno head—wedded to dark dancefloors, addicted to sonorous strangeness—chances are, you’ve heard of the book Future Shock. Published in 1970, penned by husband-and-wife duo Alvin and Heidi Toffler (herein, when I say “Toffler,” I mean both authors) and selling millions of copies, Future Shock is a book that Detroit techno’s founding group Cybotron read and which supposedly fired their artistic imaginations. “Alvin Toffler’s book is a kind of bible to Detroit’s new musical revolutionaries,” noted John McCready in 1988 in the NME (indulging in hyperbole).

The term techno was already bouncing around the global musical grid by the early 1980s. But the term’s appearance in Toffler’s follow-up book, The Third Wave, chimed with and validated the emerging electronic music genre: “The techno rebels are, whether they recognize it or not, agents of the third wave,” wrote Toffler. “They will not vanish but multiply in the years ahead. For they are as much a part of the advance to a new stage of civilization as our missions to Venus, our amazing computers, our biological discoveries, or our explorations of the oceanic depths.” A seductive idea, but decades later, how does it fare? In this jaded age of ours, while our planet burns and the dancefloor distracts, what can Future Shock still tell us?

Future visions always reflect the person doing the prediction. For the tweedy English gentleman Arthur C. Clarke, the future is about humanity’s imperial encounters in outer space. For the drug-addled vagabond Philip K. Dick, the future means inane advertisements being beamed directly into your brain and not knowing whether or not you’re actually real. For the Queer Black outsider Octavia Butler, the future involves the mutant biological blending of humans and aliens. These are science fiction authors, but between science fiction and futurist analysis, there’s a fine line, with speculation in common.

Toffler was of the privileged class of WASPs, well educated and with a background in business and journalism. Future Shock reads like the jottings of a lofty MD, the type of sensible doctor who golfs on the weekends at the country club, the trusty gent to whom concerned postwar American parents turned when their little son Billy began exhibiting worrying signs of unsavouy homosexual urges, and who would sagely prescribe Billy a thorough course of electroshock therapy. “The basic thrust of this book is diagnosis,” Toffler writes, guiding Americans through the worrying world of tomorrow.

Toffler as guide describes built-in obsolescence, modular architecture, consumerist fads, style tribes, unorthodox families. Toffler describes how we will live under the sea, weather manipulation on a global scale, “research into communication between man and dolphin,” generating new species of bacteria, synthetic body parts, cloning, choosing your embryo’s sex and personality, cyborgs. The future is a disconcerting concatenation of phenomena arising, more or less, from the revolutions in communications technology, which Toffler diagnoses and prognosticates upon.

A notable feature of Future Shock is its air of seductive exoticism. “We who explore the future are like those ancient mapmakers,” Toffler writes proudly, savoring “new realities, filled with danger and promise, created by the accelerative thrust.” The future is a strange country full of unsettling customs. As such, Future Shock is at times an escape from a mundane present into a world of romantic fantasy, of teleportation, telepathy, cloning, eternal life, bodily augmentation: futurist analysis as a branch of supernatural literature.

Future Shock is also prescient. It accurately foresees the so-called experience economy (“One important class of experiential products will be based on simulated environments that offer the customer a taste of adventure, danger, sexual titillation or other pleasure without risk to his real life or reputation”—escape rooms, Meta and so on), remarking correctly that it “is clearly foreshadowed in the participatory techniques now being pioneered in the arts” (such as hippie happenings). In art, Future Shock observes a shift away from the classical arts towards immersive multisensory experiences: “Artists also have begun to create whole ‘environments’—works of art into which the audience may actually walk, and inside which things happen… The artists who produce these are really ‘experiential engineers.’” Which is basically the 2020s techno club.

“The future is like a weird alien virus infecting the public body, mutating all the cells of human society, rendering alien and dysmorphic the human self as hitherto known.”

Much of Future Shock is a lengthy footnote to the 1960s cultural revolution. “There are rich men who playact poverty, computer programmers who turn on with LSD. There are anarchists who, beneath their dirty denim shirts, are outrageous conformists, and conformists who, beneath their button-down collars, are outrageous anarchists. There are married priests and atheist ministers and Jewish Zen Buddhists… There are Playboy Clubs and homosexual movie theaters… amphetamines and tranquilizers… anger, affluence, and oblivion. Much oblivion.” The future is like a weird alien virus infecting the public body, mutating all the cells of human society, rendering alien and dysmorphic the human self as hitherto known.

Placating us, taking seriously their self-appointed job to tell us what all this means, Toffler presents this explosion of the future as a surface symptom of a deep structural change, the transition from one technological age to another. For Toffler, humanity has been defined by three waves: The first wave was agrarian humanity; the second wave was industrial humanity; and the third wave—the future exploding so strangely around us—is superindustrial humanity. Others have called the latter post-Fordist or postindustrial society, an economy no longer based on manufacturing but on services, no longer based on things but on information, a globalized world networked by information technology.

“The inhabitants of the earth are divided not only by race, nation, religion or ideology, but also, in a sense, by their position in time.”

“The inhabitants of the earth are divided not only by race, nation, religion or ideology, but also, in a sense, by their position in time,” Future Shock states. “Examining the present populations of the globe, we find a tiny group who still live, hunting and food-foraging, as men did millennia ago. Others, the vast majority of mankind, depend not on bear-hunting or berry-picking, but on agriculture.” In this view, all wars are effectively wars between different waves. Toffler describes the West as a system in a state of disequilibrium, waiting to settle again into a steady state. Adaptation will be key, informed by understanding.

Toffler is particularly focused on how modern society’s exhausting sense of endless transience affects our sense of self and of social connections. For Toffler, the twentieth century Western world’s explosion of consumer goods is one of the main indices for the third wave’s accelerated rate of change. We ourselves might measure the changing rate of change through the ubiquity of smartphones, the personal computers through which we mediate and zombify ourselves. Only ten years ago, not everyone had one, but now, it seems unimaginable that things were ever any different. The rapid change could not but leave some feeling existentially fraught, daunted by how suddenly our inner lives have been surrendered to surveillance capitalism.

“Future shock is the “shattering stress and disorientation that we induce in individuals by subjecting them to too much change in too short a time.””

Which brings in Toffler’s most famous concept, the titular future shock. “Future shock,” Toffler writes, is the “shattering stress and disorientation that we induce in individuals by subjecting them to too much change in too short a time.” The neologism is coined by analogy with culture shock, what happens to a Westerner when they fly to a far-flung place and throw themselves into a completely foreign culture, Delhi, say, to head-spinning effect. Psychologist Sven Lundstedt defined culture shock as a “form of personality maladjustment which is a reaction to a temporarily unsuccessful attempt to adjust to new surroundings and people.” Expanding on this, Toffler defines future shock as “what happens when the familiar psychological cues that help an individual to function in society are suddenly withdrawn and replaced by new ones that are strange or incomprehensible.’

For the future-shocked person, “the strange society may itself be changing only very slowly, yet for him it is all new. Signs, sounds and other psychological cues rush past him before he can grasp their meaning. The entire experience takes on a surrealistic air. Every word, every action is shot through with uncertainty. In this setting, fatigue arrives more quickly than usual.” Acceleration, change and adaptation are key concepts assumed by this framework. Through providing an explanation of what’s going on at a deep structural level, Future Shock helps Joe and Jane Middle America adapt and regain stability amidst the typhoon of transformation. “The problem is not, therefore, to suppress change, which cannot be done, but to manage it. If we opt for rapid change in certain sectors of life, we can consciously attempt to build stability zones elsewhere.” And, indeed, to capitalize on it: one of Toffler’s later books is called Revolutionary Wealth: How It Will Be Created and How It Will Change Our Lives.

As I close Future Shock’s covers, my main takeaway is a contrary view. I am not a past person forced to live in an environment of the future; I am a future person forced to live within the environment of the past. I have past shock. The tyranny of the everyday—of conventional national identity, sexuality identity, gender identity, personhood at all in the first place—is completely bewildering. It has shocked me my whole life. I do not want to absorb the future into the everyday and thus to tame it: I want to be drained of all pastness and absorbed into a futurity that can never be contained within any earthly roots.

Techno helps me to do that. Within the club’s darkness—through immersion in flickering lights and out-there sounds and rhythms like insect heartbeats—techno envelops you in silence. Then, techno whispers that yes, what you feel despite it all is real, that history is madness and selfhood a fantasy. If a techno set by, say, Jeff Mills provokes shock in us—shock at its relentless strangeness, through its insane electronic loops—it is a shock we should embrace, recognizing as it does our real self, our future self.