#ZUKUNFT: “TRANSCENDENCE AND DIVINITY: DELIA GONZALEZ”

Delia Gonzalez’s exhibition, “Fassbinder Has Wings, Fassbinder Can Fly,” showcased…

Words by Jazmina Figueroa

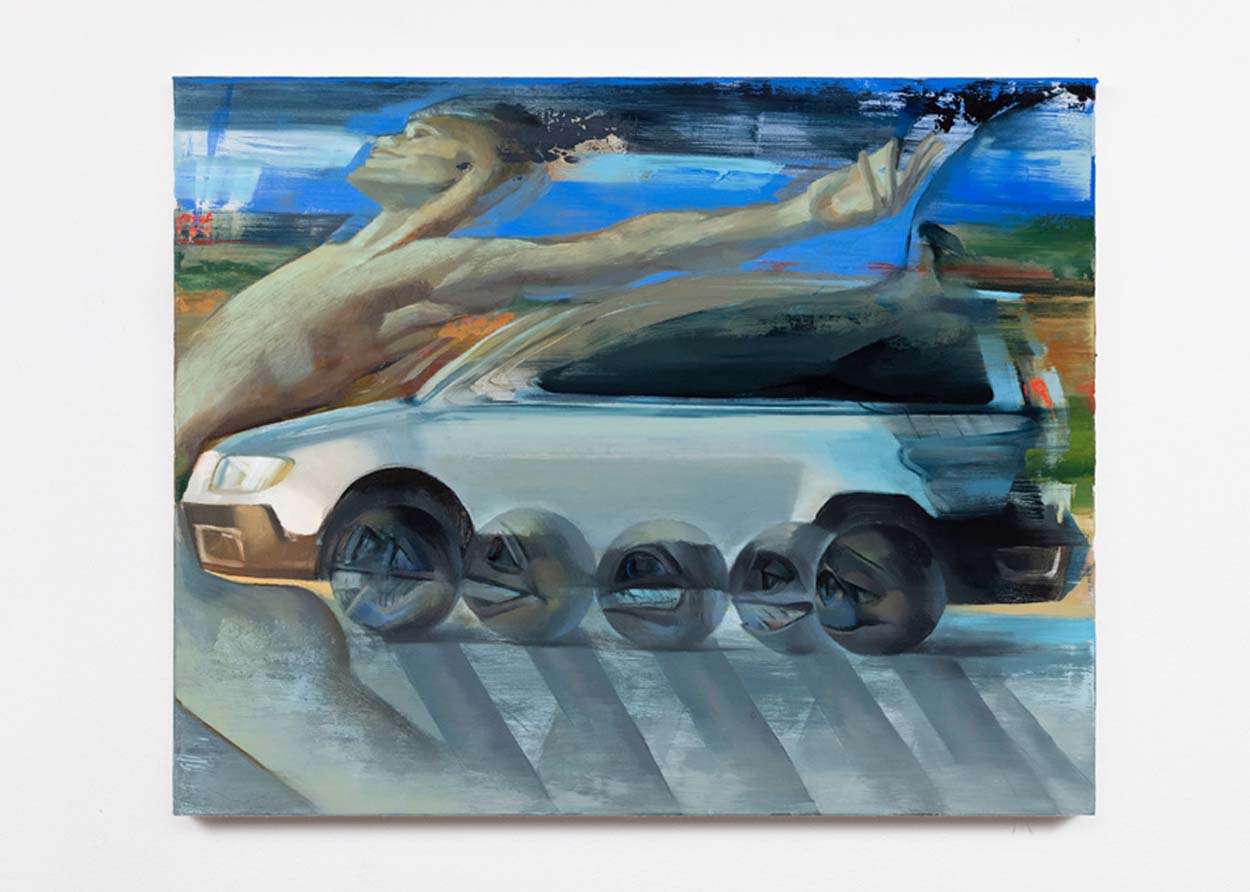

I think, ultimately, what the work of Alexa Hawksworth trades in is tension, a productive refusal of positioning herself or her subject matter either here or there. This is not a product of laziness, but the technical and conceptual output of a painter dedicated, if not hellbent, on the pursuit of a formal ideal that seeks to visualize the fundamentally unrealizable, a painterly and quasi-desperate grasping at transcendent ideas, from desire to psychological and physical stasis. Indeed, it is the volatile, contradictory and semi-hallucinogenic qualities of her work that perhaps position her tableaus as one of the most cutting and incisive documents of the psychosocial status of our age.

Born in 1994, Hawksworth’s paintings formally mirror a breadth and width indicative of her literary and cultural interests. In conversations and studio visits I have had with Hawksworth, her repertoire of reference points run a large gamut, from the Manson murders to Kandinsky’s writing on the spiritual in art, from the writings of the political-activist-cum-mystic Simone Weil to the finer points of car advertisements, and from the oeuvre of Cassavetes to shanzhai culture (a Chinese term that roughly translates to the term “counterfeit,” although far more expansive in scope versus its English counterpart). Regardless of the theoretical point of departure, Hawksworth’s distillation of her references result in paintings that bear both spiritual and psychologically charged connotations, without any clear delineation between the two. Working primarily with figuration, the subjects that populate Hawksworth’s images appear torn, not in the sense of flesh ripped asunder or in a state of degradation, but as if multiplying, or being pulled out of a singular body.

Take, for example, Blow Out II (2022). Shades of cool pigment — primarily varying shades of blue and a few slivers of mossy green — wash over the canvas, clashing with the warmer hues evocative of sunset and sun-burnt flesh in the upper middle and left hand sections. These areas of pigment meet in the middle, resulting in an almost nauseating mix of brown and orange, calling to mind both decomposing bio organic material and obnoxious LED club district lighting. Forming the fulcrum of this composition is a flattened purple figure, gesturing upwards, on either the tips of their toes or in a pair of heels. The figure (which bears a funny resemblance to the Insane Clown Posse logo via its wild mane of hair and its rendering as a silhouette) is one of the instances in which we can see the sort of “tearing” or dislocation I mentioned. Swirling around the space of the canvas are a number of other figures whose relation to the silhouette in the middle remains ambivalent. To the left, a screaming figure in a bikini top almost appears to flit out of existence, given the opacity of its torso versus the semi-transparent ephemerality of its arm. To the right, a pinkish-white figure looks to be in the midst of being rapidly pulled towards the silhouetted figure, as if it were an anthropomorphized black hole. Meanwhile, two floating, emoji-like faces make their way across the middle of the silhouette’s chest. In a sense, Blow Out II appears to be an image of psychological or spiritual splitting, a scene of the soul or psyche leaving the flesh.

Further, the tension in Hawksworth’s paintings plays out on a secondary level, namely, at the level of speed. It is perhaps this dimension that lends her work a sublime quality, akin to the work of J.M.W. Turner in his portrayals of steamships barreling across the open seas. And it is perhaps this dimension that veers Hawksworth’s work into the arena of history painting. The elucidation of the relationship between speed and history was the central focus of the writings of urbanist Paul Virilio, particularly in his aptly named Speed and Politics, who noted: “The focus of my research has shifted from topology to dromology i.e., the study and analysis of the increasing speed of transport and communications on the development of land-use.” Virilio’s notion of dromology, in short, is to think through societal changes first and foremost through the vector of speed. Virilio suggests in his writing that technological development within contemporary society places speed of transport, movement and communication above all, resulting in profound ramifications on the human subject, namely the compression of our experience of time and space. However, this bent poses a threat: Virilio argues that this obsession with speed increases the risk for accidents, errors and catastrophe through the reduction of time and space with which to think or reflect. Although this text is not without its faults, is speed not one of the defining features of the 21st century? Is speed not often positioned as an object of desire within so many ad campaigns, with promises of immediacy through buzzwords like “now,” “faster” and “on-demand”?

Speed manifests itself in Hawksworth’s work as a subtle sort of leitmotif. Blow Out II appears as a scene of the soul or psyche splitting off from the body, but these figurative off-casts are not content with merely hovering and haunting the silhouette in the center; they whip about, in a stirred frenzy. This theme emerges in a number of Hawksworth’s other works, including Lazy Susan (2022), Eclipse (2021) and Blow Out III (2022), among others. In a sense, painting is a prime medium for the depiction of speed: a naturalistically rendered object, when obfuscated or “pulled” or “stretched” by the deft application of paint, mirrors the blurred optical effect experienced when the retina fails to keep up with a passing object in motion. Indeed, speed has been one of painting’s fixations from its inception. Paintings in the Chauvet Cave from the Upper Paleolithic period depict herds of ice age animals in motion, as suggested by child-like speed lines that surround many of the figures. Other elements of the Chauvet Cave act as a Promethean forerunner to some of the techniques applied by Hawksworth. Therein, animals from the same species are portrayed clustered together (perhaps to emulate a herd) and oriented in the same direction. It gives the illusion of one single body moving rapidly across space, similar to the emoji figures in Blow Out II.

In the millennia following the execution of the images in the Chauvet Cave, speed has repeatedly been employed in the service of painting as a means to index the sensorial qualities of a given age. Of course, there is the aforementioned J.M.W. Turner, whose impressionistic scenes of steam-powered vehicles pointed to a new understanding of the British landscape, as the time necessary to traverse the country quickened and its spaces became seemingly more compressed as a result. In the Italian context, we can look to the Futurists, who saw speed and technology as tightly bound to their own historical zeitgeist (although it may act as a cautionary tale against harnessing technology in the service of a fascist worldview). On occasion, standstill (as a negation of speed or movement) has produced the same effect. Edward Hopper’s tableaus of solitary figures in early 20th century American cities function well as psychologically-charged historical documents; by contrasting stillness to the usual hustle of the metropolis, themes of urban alienation and atomization crystalize out of the anonymous urban blur.

I would argue that Hawksworth’s work follows this path, indexing the psycho-sensual qualities of our age into the medium of paint and the motif of speed. In a conversation I had with her, she explained that the formal tendencies in her work ranging from about 2020 to 2022 emerged as a reaction to the conditions experienced under COVID-19. Namely, the isolation produced by lockdown and the feeling that one could go nowhere but their own mind. This feeling of psychological alienation must be considered in dialogue with our changing relationship to technology. 2020 marked the transformation of a world that was becoming increasingly online through the ubiquity of smartphones, to a world that is now terminally online, thanks to the normalization of work-from-home and the fact that the internet was one of the only points of connection we had to the larger world during the pandemic. The reduction of our access to physical space and contact forced us onto the digital world wide web. Our bodies may have been confined to a very narrow set of spatial coordinates, but our minds were pushed to stray at an ever-quickening pace.

This tension comes to light with a particular clarity in Hawksworth’s Lazy Susan (2022), which she produced at the height of COVID-induced alienation. In this work, which was shown in New York City’s Theta Gallery last year, a blonde figure spins in place at a breakneck pace from a central axis, one leg slightly raised as if in a pirouette. Due to the rapid motion, the figure has multiple heads and arms and legs, as if some kind of warped Web 3.0 Avalokiteśvara. A bright light emanates from its center, obscuring the visibility of the torso, while the hands and head seem constrained or hemmed in by a series of floating squares, calling to mind screens or interfaces. If it were not apparent at this point, there is a psychological bent to Hawksworth’s images, reflected in the figurative splitting I mentioned earlier and the expressions of her figures, who display a variety of emotions, but often blown up to hyperbolic extremes. These formal investigations into the psyche are reflected in the ideas that have come up in our conversations, regarding the expression of one’s psychological state, the formation of desire, and the understanding of the self. If we are to read Hawksworth’s work as a sort of externalization of the psyche, her work would in turn evoke the words of painter Max Beckmann, who described his images as the rendering of the “objectivity of inner visions”: His expressionistic and abstracted paintings of the social underbelly of the Weimar Republic are naturalistic precisely in the sense that they portray the objective world as it is psychologically experienced by the painter.

Evidently, technology is part of this process of psychological formation, an interest evoked by Hawksworth through works like Developer (2021) and a small-scale painting of a 5G tower. This work also falls under the rubric of her speed motif; a human figure with an impossibly elongated neck and an emoji-like head appears to anxiously pace the space of the canvas, hunched over, grasping or swiping at a missing object. According to Hawksworth, the work interrogates the idea of social or technological progress by evoking a figure transfixed on the compulsive development of new tools without asking if this progress is truly additive. In her terms, the work brings up the tension between “motion and stasis” and “everything and nothing.” The latter dyad in particular calls to mind Virilio’s words in Information Bomb: “… the computer is no longer simply a device for consulting information sources, but an automatic vision machine, operating within the space of an entirely virtualized geographic reality.” Surprisingly, this line was published in 2000, and thus could not have possibly anticipated the effects of the mass propagation (and ubiquity) of what are functionally hand-held computers. In a way, the geography of the globe has now been reduced to a series of small squares. In tandem with this spatial reduction is of course the speed in which we experience the world; communication is instantaneous, goods of all kinds are available at will, and even the development of cultural tendencies and trends appears to be quickening. There is a feeling that everything everywhere is available all at once and yet we feel stuck, stuck in the face of new theaters of war, in the face of ecological disaster, and in the face of our continued economic downward spiral. It is for these reasons that Hawksworth’s paintings have arguably entered the arena of history painting. Not because they portray newsworthy events or scenes, but because they capture the essence of our psychological zeitgeist, drawing attention to the strange brew of contradictions that we now live in. Between everything and nothing. Between motion and stasis.

Delia Gonzalez’s exhibition, “Fassbinder Has Wings, Fassbinder Can Fly,” showcased…

Words by Jazmina Figueroa

Artist duo Cooking Sections’ work combines art and activism, using food as a gateway to…

Interview by Johanne Björklund Larsen

Just because a bed is empty, doesn’t mean it can’t be filled with longing.

Interview by Angela Waters