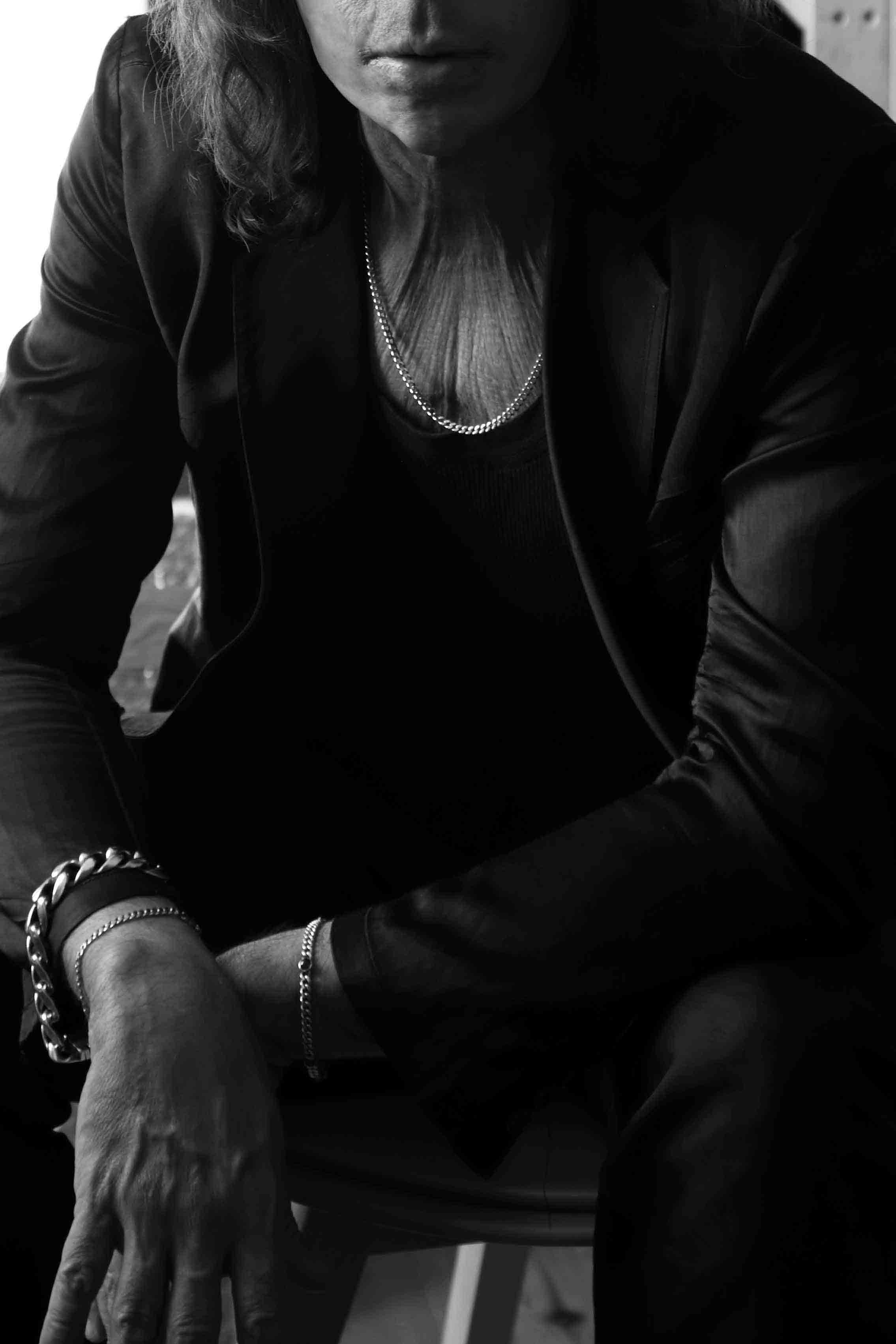

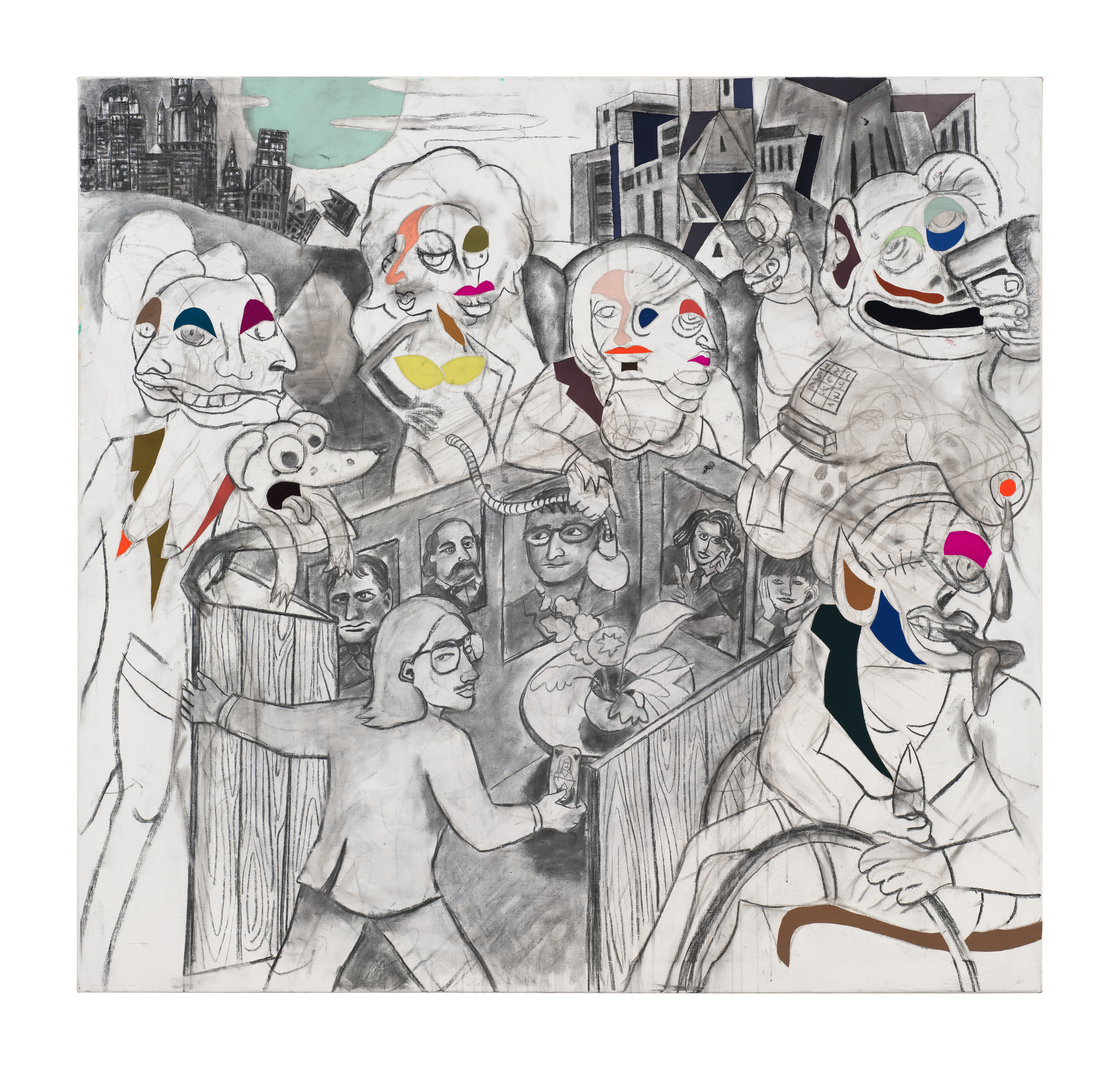

When I first encountered Armin’s paintings, I was drawn into them as though entering a fever dream. His vibrant worlds teem with obscure personalities, subtle messages, and an undercurrent of unseen abysses. One could spend hours before them and still uncover new details. The same holds true for the painter himself – an entire novel could unfold in conversation with him. For this issue, I met him in his studio to discuss the theme of fighting, a subject he knows better than almost any other artist.

Armin Boehm: Without sounding dramatic, I’d honestly say the biggest fight was literally for my life – because I almost lost it in an accident. Between the ages of 16 and 21, my biggest struggle was simply to recover. The explosion set my body back by years. I couldn’t do the things others my age were doing physically. I had to reinvent myself, to build a new identity. I felt different – like an alien. For years, I lived with pain, fear, and near-death experiences. Becoming an artist was never my dream or goal. I had very different problems. Maybe you’re born an artist without even realizing it. But that fight for survival, and the confrontation with my own mortality, awakened something in me that had long been dormant.

AB: Not at all. I come from a family of engineers, lawyers and businesspeople – art wasn’t a big topic in our house. I was a pretty rebellious child, so my parents only offered moderate resistance when I decided to apply to art school. I think they also just couldn’t picture me working behind a bank counter or in an office.

AB: I’ve been drawing for as long as I can remember. And when I was halfway recovered, I started working with oil paints. As a child, I used watercolors, but they dry so fast. Oil paint was different. There was this silky, beautiful sensation – you could build entire atmospheres with it and completely lose yourself in the process. I walked around like a young bohemian, always dressed in black, wearing a beret. As soon as I got my driver’s license, I started traveling to Paris. I’d go to the Louvre, photograph the paintings that spoke to me, and develop the photos at home so I could study them closely. During my recovery, I gradually got lost in this universe of painting. Maybe it helped that my body was still very restricted – painting didn’t require intense physical effort. My hands were intact, and my eyesight slowly returned. Painting became a world I could immerse myself in. I wanted to live and work in that atmosphere beyond the everyday. I was drawn to the darker, metaphorical paintings of the past, and to the unconventional lives of the artists behind them. After visiting the Louvre, I’d often head to Père Lachaise Cemetery to visit the graves of painters, poets and musicians.

AB: No, for me, art was never therapeutic. It was the doctors, my friends and my family who really helped me through. Right after the hospital, I had to fight to regain my vision – I could barely see. Art only became possible once I’d fought for my health. But once painting became important to me, a new kind of struggle emerged. Entering the art world means stepping into a different kind of battlefield. I applied to art school thinking I’d get in right away. But they rejected me three times. “We see no artistic talent. We wish you all the best in life.” That’s what they said.

“I never had a “strategy.” Since the accident in 1988, I’ve lived like an animal – always in the moment.”

AB: It gets worse. I had just gone through a tough eye operation and was a total wreck – emotionally and physically. Then my girlfriend broke up with me. I came home from the hospital to our shared apartment and she was gone. It was devastating. And the very next day, I had an interview with Jörg Immendorff, who was already a big name in Germany. I wasn’t particularly into his paintings, but I was interested in him as a person. I wanted to join his class. So there I was, a young artist in a beret, showing up with my portfolio. He looked at my drawings, and the first thing he said was: “Why would a young person draw nudes? You’ll never get anywhere. Goodbye.” He thought it was too academic and uptight. So I gathered my things – papers falling out of my folder – and left. But even though I was at my lowest, I felt a fire inside. I said to him: “I’ll be back. You’ll see.” That was the beginning of a fight with him. I didn’t give up. I ended up spending two years in Konrad Klapheck’s class instead – which turned out to be a lucky break. It was a more intellectual environment, and the battles fought there were on a different level.

Later, I ran into Immendorff again – by chance, in an elevator. I said, “I’d still really like to be in your class. Could I show you some new work?” And in that elevator, with his deep voice, he said: “Let’s see.” I always photographed my work, so I had some pictures with me. He looked at them and said: “Yeah, the heads are good. I find what you’re doing interesting. Come join my class.”

He acted like he didn’t recognize me – but I think my face is hard to forget. His teaching assistant didn’t like me at all. He claimed I was more interested in women than in painting. But luckily, Immendorff didn’t let that influence him.

“It’s a choice whether or not you see yourself as a victim. I always refused that role.”

AB: Immendorff was always surrounded by beautiful women and some pretty wild guys from Hamburg’s red-light district. Studying with him was controversial – he had a bad reputation. At the academy at that time, there was a very liberal, uninhibited atmosphere. At the same time, students were expected to take responsibility for themselves and take risks. I was searching for something anti-bourgeois and anarchic.

AB: In the beginning, I was very insecure, fragile, and cautious in how I moved through life. I was still recovering and wasn’t ready to make radical decisions. At first, I tried to compromise and enrolled in art history and law. But after one semester, I realized I couldn’t live among normal students. The weed-smoking, the recycling obsession, that eco-collective mindset – it got on my nerves. I felt even more out of place in that academic environment than I had in the small town I came from.

Things changed when I got into the art academy in Düsseldorf. There was this sentence carved in stone: Only the best for our students. I liked that elitist flair. And those huge rooms with the Greek sculptures – that was the atmosphere I wanted to live in. I knew I belonged there, even if I couldn’t explain why.

AB: Right after I left the art academy – without a degree – I had an exhibition in a gallery that was pretty up-and-coming at the time. I also started taking part in art fairs early on. The gallerists told me they thought I was a good artist and wanted to work with me long-term. I felt like I had been welcomed into a family. I thought we were going to fight together for a position in painting. But then I had a year where I just didn’t make good work. I had a crisis. Suddenly, someone said to me, “Hey, look at your gallery’s website—you’re no longer listed as one of their artists.” The gallerists had just dropped me without a word. That’s when I realized what kind of shark tank I was in.

I eventually found another gallery that showed my work. And when a bigger gallery saw my paintings there, they asked if I wanted to exhibit with them. And the whole game started again. The moment you’re no longer interesting, for whatever reason, you’re discarded.

Despite all that, I believe an artist should stay true to their own genetic code – deal with the things that truly grip them, that they feel compelled to pursue. Promises don’t really count for much. One time, a major curator visited my studio and promised me a big solo show in his institution. That was huge. But later, his chief curator worked against me and the show never happened.

Still, I kept working for myself and kept going. For many years now, I’ve had a younger artist working as my assistant – he’s like a brother to me. That’s loyalty. A kind of loyalty I’ve otherwise only experienced in family. That solo show eventually happened – in another city.

AB: Of course not. But if you’re doing something out of passion, if you truly love what you do, then you can endure the pain of the inevitable setbacks. Just keep going. That at least increases your chances of success.

AB: The journey was always the destination. I never had a “strategy.” Since the accident in 1988, I’ve lived like an animal – always in the moment. That’s not meant to sound romantic, but it’s true. I don’t have a goal in the traditional sense – I just work, and then, from that work, a new goal emerges. In painting, you’re also working on a kind of human development. Art, in some way, is tied to becoming human.

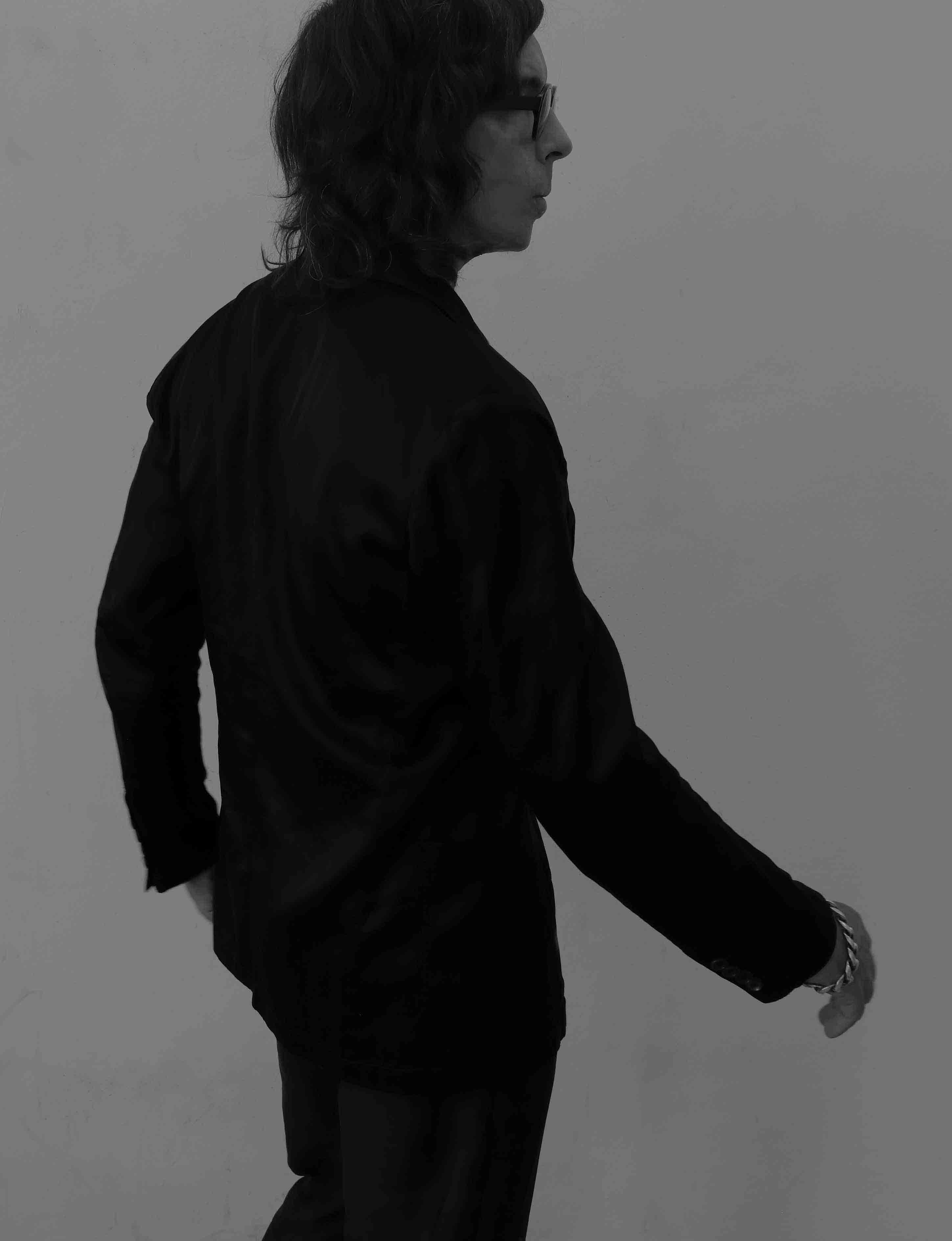

AB: Quite the opposite. The most important thing I’ve learned from my battles is how vulnerable I am. I don’t like “coolness.” To me, it’s more a sign of insecurity. Experiencing defeat, rejection and pain – and growing through it – that’s the real secret of struggle. It’s a choice whether or not you see yourself as a victim. I always refused that role. I never wanted to be a victim. Of course, you should always expect that something might happen, but you shouldn’t live in fear. I take care of my health. I try to stay in shape – mentally and physically.

AB: Maybe also out of vanity. I like when my suits fit well, so I eat healthy to stay slim. I don’t drink alcohol because I paint much better when I’m sober and well rested. When I’ve had alcohol, I can’t make good decisions the next day – like how to combine colors.

AB: Sure, I know that. When Johann König recently offered me my first solo show at his large gallery in Kreuzberg, I agreed. But secretly, I doubted whether I could handle the space – especially with my dense, politically charged paintings. I wasn’t sure if they would work on those walls. I was terrified of failing. In the middle of preparing for the show, I was also dealing with very painful private issues. Naturally, I thought about relocating the exhibition to smaller rooms. But I transformed the weight of that personal crisis into something else through painting. I used the negative energy to create something positive – like in judo, where you use your opponent’s force to your own advantage.

“The most important thing I’ve learned from my battles is how vulnerable I am. I don’t like “coolness.” To me, it’s more a sign of insecurity. Experiencing defeat, rejection and pain – and growing through it – that’s the real secret of struggle.”

AB: I find the blend of art and activism problematic because you’re not really centered in yourself when you join a collective movement. My temperament doesn’t suit that. As I’ve said before, I’m pretty stubborn and not exactly group-compatible. I’d constantly have to compromise within an activist movement, and that’s not my thing. I think activism in the art world often is little more than virtue signaling. Marketing, really. I’m tired of people who parade their good intentions “on behalf of others.” Usually, it’s just about their own egos – or money. I prefer to look at actions, not words. I’ve had bad experiences with well-meaning talk.

AB: Pain is just a state of being, like exhaustion or ecstasy, joy or lust, fear or boldness. As I’ve said, I can use all these states for my painting. But a painting can also cause pain – every painting demands something from me. I have to devote myself to it and sometimes put my own feelings aside for the sake of the work.

AB: I think pain has something isolating about it. Everything inside me contracts when I’m in pain – and that sometimes helps me focus better on painting. I might even see different colors or choose more extreme tones because of that pain. Of course, it depends on the kind of pain. Emotional pain – grief, despair, depression, heartbreak – has often led to intense works of art. It isolates you, draws you away from people and society. Personally, I’ve often started new chapters in my painting after painful moments in my life.

Sometimes, a painting can feel like an opponent – when I’m stuck. A painting has its own logic. I’ve often learned that I can’t simply impose my will on it. I have to understand where the painting wants to go. If that doesn’t work, it becomes the classic battle with the canvas. That happens. I’ve had to cancel exhibitions – even during peak times – because I just wasn’t getting anywhere. I couldn’t access the work, and that was painful. It can be paralyzing.

AB: I often compare paintings to children. You can control them up to a point, but at some stage, you have to let go and follow them – they develop a will of their own. And if you don’t let them go where they want, it causes problems. If, for whatever reason, I can’t engage fully with the painting, it becomes really agonizing. Then I start to see it as an opponent.

AB: Yes, there are times when I give up and say, “I’m stuck.” But it’s more like a break in the battle. I’ll put the painting somewhere out of sight, and eventually, I’ll have an idea – it starts speaking to me again. Paintings hold time within them, like it’s been preserved. Years later, I can still see which parts gave me trouble – where I scrubbed things out or kept layering paint over and over.

AB: I don’t like explaining my paintings, because my explanation is just one of many. That would only narrow their meaning. I can only tell you what I see when I look at them. In my political, social paintings, I see types of people I recognize today – though they’ve probably always existed in different forms. The double faces and grotesque exaggerations are just my sober observations of contemporaries. The digital masquerade we take part in today is not so different from the hierarchical masquerades at 17th-century courts – or the moral masquerades painted by Hieronymus Bosch. I try to depict reality without aestheticizing it, and without relying on drugs or substances like the Expressionists or New Objectivity painters did. But I do use a kind of gesture that might recall those times. Maybe we’re fighting similar social battles again today.

AB: I like the role of the observer because it suits my nature. I enjoy painting cats – they’re observant animals, too. As I mentioned, ever since that failed youth, I’ve had this feeling of being a guest. I never really wanted to participate fully. Once, my music teacher asked me, his face flushed red, whether I actually felt like just a guest in this world. I paused briefly and then said, “Yes. You’ve nailed it!”

AB: No, I wouldn’t say that. Painting shouldn’t be used as a kind of therapy. In art, everything is just material. Including myself – I’m just material, too. A substance, something I can process through painting. If I’m lucky, maybe I’ll manage to add something to the history of painting. But that’s not for us contemporaries to decide – that’s up to the generations after us.

AB: But none of this is new. These experiments with personal emotional states already happened in the 60s and 70s – with well-known results. Simply repeating all that today is the opposite of progressive art. Why should I bother with it? What interests me are radical artistic positions that communicate with me across time. A compelling artistic idea can be sent out in a century long past – like a letter – and you receive it, sometimes centuries later, and continue the work. A painter like Maria Lassnig, for example, really engaged deeply with her own physicality, despair and emotional state – and created radical painting from that. That’s the kind of thing I find compelling.

“Courage is the sexiest thing there is. I love people who are brave. And in everything I do, I always try to be a little braver than I actually am.”

AB: I know I’m a rather analytical person. That can actually get in the way of my painting. So I make a point of allowing foolishness and spontaneity. I let go of control and give chance more room in order to arrive at different images. I pick up things spontaneously – fragments from conversations, the internet, films, books, words, slogans, memes – anything. The result takes on something collage-like, playful. I often paint best when I’m on the phone or have people over and we’re talking. Because then I can’t overthink the painting as I’m making it.

AB: Both can help me. In the end, they’re just dismissive terms that suggest the painting has failed. But failure always involves risk and a sense of falling. As I said, I’m not a strategic painter. I don’t care for art that always plays it safe, that tries too hard to look like postmodern, international, glittery, design-like art – with no local character. That kind of art ends up being sleek and stylish, but it disturbs no one.

AB: I find it fascinating – this willingness to do something foolish. I think we do it far too rarely in life. Foolishness can be refreshing, especially for someone like me who tends to overthink. So, I often just start doing something first and think about it later. In my painting, I like to experiment with “stupid” subjects. Even if I end up discarding them, maybe a line or a bit of color remains – something that disrupts the image. It leaves a kind of crease, a kind of wound.

I’ve noticed there’s a growing need to control how one’s biography, work and persona are presented to the outside world. Less and less is left to chance. AI filters remove facial and bodily flaws. Maybe one day this will be called the Botox era. Personally, I’m drawn to the imperfections in people, and the awkward or illogical parts of a painting – those are what spark my interest. That’s how I find a way into a work, or connect with a person. I like the overlooked images, the fringe figures – both in painting and in life.

AB: I tend to be drawn to the villains, too. Like in the James Bond films – the one with the eye patch and the cat. The villains are often portrayed with much more psychological complexity. The Joker in Batman is another example – he seems so heartbreakingly real. Film noir, or the characters created by David Lynch or John Ford, always remain morally ambiguous – just like people in real life. I don’t have much hope when it comes to humanity. But I do believe that art holds the potential for growth and becoming truly human, if one dedicates themselves to it.

AB: I had pretty strict parents and was a terrible student. My teachers didn’t like me, and my parents usually sided with them. I remember that drawing and my imagination already helped me as a child to be liked. Later, when I fought my way back into life, I had to fight for acceptance – to avoid being seen only as a victim. My accident happened right when I hit puberty, so on top of the usual identity crisis, I also had an existential one.

Wanting to be unconditionally loved through your art can be dangerous in this era of influencers and likes. There are so many temptations through market strategies – it can interfere with the work just as much as political activism can.

I think, contrary to Joseph Beuys, we need to re-enter art. Bazon Brock wrote beautifully about this. As I said before, I live in my own cosmos, a world that requires effort to enter and ultimately offers no promise of happiness. On the contrary – painting often leads to disappointment. You spend a lot of time alone, often unseen and even less understood. I don’t believe in reflecting on what makes you happy or what happiness even is. You work, you stall, you work some more – and then you die.

“I like the overlooked images, the fringe figures – both in painting and in life.”

AB: It’s actually the opposite. I used to just want to be left alone. So many people messed with me – doctors, teachers. I wanted to get as far away from all of that as I could through art. Into a space where no one could interfere. I do enjoy being around people, but I rarely attend openings and avoid big events in the cultural scene. But the people I’ve met there who became my friends – I have very deep and intense relationships with them.

All I can do is encourage people: Just do your thing. Don’t orient yourself by what others expect of you. Courage is the sexiest thing there is. I love people who are brave. And in everything I do, I always try to be a little braver than I actually am.

AB: It’s much easier when you don’t take yourself too seriously and learn to play with your own identity. Who are we, really? For a few years, we wander around thinking we’re something special. Then we just vanish. Nietzsche had this fantastic metaphor in Zarathustra:

First, you are a camel – you load yourself up with knowledge.

Then you become a lion – you free yourself from rules, from duties, from all that you’ve learned.

Finally, you become a child again – who plays freely with all the broken pieces and reassembles them.

When I feel that almost childlike freedom in me to play – with what’s inside me and around me – through painting, that’s when I can work best. Having gone through defeat and pain is part of it. I even have to destroy my own certainties again – revolt against myself. That’s the most beautiful kind of fight.

FIGHT ISSUE VOL. B – Glen Martin Taylor

Glen Martin Taylor: TENDERING THE FIGHT

“VISION MEANS TRUSTING THE UNKNOWN”— A CONVERSATION WITH HANNAH HERZSPRUNGBY ANN-KATHRIN RIEDL

"CREATIVITY OFTEN…

Celebrating the launch of “Vanille Caviar”: In Conversation with bdk

Last month, for the launch of their new scent "Vanille Caviar", Paris-based perfume house…

WEEKEND MUSIC PT. 72: IN CONVERSATION WITH BARAN KOK

Inspired by artists like Kurdo and Haftbefehl, German rapper Baran Kok set out to make a…

STRAIGHT TO THE HEART – GUERLAIN CELEBRATES A CENTURY OF LOVE

Guerlain celebrates 100 years of Shalimar with a special exhibition in Paris that explores…

By Ann-Kathrin Riedl

“IMAGINE” at Kunstraum Heilig Geist: Make it simple but significant

Stravoula Coulianidis in conversation with artist Yves Scherer