“I WANT TO ACKNOWLEDGE SOME OF THE WRITERS WHO, THROUGH THE UNAPOLOGETIC POWER OF THE FIRST PERSON, SHAPED THE HUGO I AM TODAY – THE ONE WHO IS SO FAR FROM THE BOY WHO ONCE WROTE HE’D RATHER BE DEAD THAN WHO HE IS, NOW WRITING THESE VERY WORDS.”

The other day, while home for the holidays, I went through my teenage belongings and stumbled upon an old journal. It was almost endearing – bad prose recounting my daily life with an intensity that, at the time, felt like the weight of the world. Pages filled with arguments involving names I no longer recognize, gossip about crushes, betrayals, and parties I wasn’t invited to, complaints about teachers, and defiant scribbles reject-ing my parents’ authority. The usual. I thought my experiences were so singular and unique, and fifteen years later, they read like the script of a coming-of-age drama. All these clichés I once believed were mine alone. At some point, the pages darken. “They locked me in the locker room again,” I wrote in 2011.

“They keep calling me a faggot.” A few pages later, another entry: “Mélanie asked me if I like boys or girls. What kind of question is that? Girls, of course.” More family disputes, more middle school gossip. Then: “I can’t stop thinking about it. I asked people on an internet forum, and they think I might be gay.” (I smiled as I read this, re-membering how I had created a profile on the family computer, navigating niche websites, typing: “Hi, my name is Hugo, I’m 13, and I think I might be gay. Am I gay?” Anonymous users with pixelated avatars would reply: “Yeah, probably :/” And I’d cry.) I’d cry, then turn to my notebook and write sentences that, years later, would cut just as deep: “If I’m gay, I’d rather be dead.” I stopped on that sentence for a while. There was a point in

my life where I thought I just wouldn’t make it out alive. I felt so rejected by the norms around me that it just felt simpler to imagine not being a part of them at all anymore. What stands between myself now, a twenty-some-thing living in Berlin and writing stories for a living, and this teenage self? The End of EddyIn, his 2014 debut novel, Édouard Louis writes about growing up as a gay boy in work-ing-class rural France. He writes about being beaten, humiliated, and ter-rorized – about existing as a “faggot,” the lowest of the low. Nothing equips him to protect himself from the shame and fear that accompany him everywhere, and so he internalizes it. He tries, over and over, to em-body the masculinity expected of him, and each failure convinces him the fault is

“THERE WAS A POINT IN MY LIFE WHERE I THOUGHT I JUST WOULDN’T MAKE IT OUT ALIVE. I FELT SO REJECTED BY THE NORMS AROUND ME THAT IT JUST FELT SIMPLER TO IMAGINE NOT BEING A PART OF THEM AT ALL ANYMORE.”

entirely his. Yet, in turning his life into fiction, in writing his own story, he grants himself the possibility of salvation. He embraces a way out. I first read The End of Eddy in my fourth semester of university, and it felt like someone had written about my very experience. The shame and pain he was describing were mine, the context similar, his trajectory so relatable. It felt almost painful to read. My professor had said that week, as we were analyzing the text and many of us were pointing out our identification with Louis’ prose, that this is what queer storytelling could do to you – it touches on the foundations of your sense of self, even if the story of another person is fundamentally never fully yours.

Queer storytelling is not simply about an LGBTQIA+ individual crafting a narra-tive. It is the assertion of the “I” – fictional or autobiographical – as an act of reclaiming agency. Queerness, at its core, is a story – a narrative his-torically imposed from the outside, shaped, disciplined, and appropriated by heteronormative structures. A queer story exposes the mechanics of storytelling itself by reclaiming both the self and the power to tell one’s own story. As complicated as terms like queer literature and autofiction may be, what matters most is storytelling’s transformative power – not only in shaping narratives, but in articulating identity itself, in allowing it to be explored, understood and reclaimed.

Perhaps this is not an act of transformation so much as an act of articulation, given that queer people have so often served as vessels for stories that are not their own. If we do not tell our own stories, they will be told for us.

This is why The End of Eddy made me resonate with my own shame and development. I had to think of this book as I skimmed through my teenage journal and the violence I was translating in it. Finding it in Edouard Louis’ book made me feel less alone; it made me feel connected.

IF WE DO NOT TELL OUR OWN STORIES, THEY WILL BE

TOLD FOR US

“THIS IS WHAT QUEER STORYTELLING COULD DO TO YOU – IT TOUCHES ON THE FOUNDATIONS OF YOUR SENSE OF SELF, EVEN IF THE STORY OF ANOTHER PERSON IS FUNDAMENTALLY NEVER FULLY YOURS.”

“THE SHAME AND PAIN HE WAS DESCRIBING WERE MINE, THE CONTEXT SIMILAR, HIS TRAJECTORY SO RELATABLE. IT FELT ALMOST PAINFUL TO READ.”

In The Velvet Rage, Alan Downs writes that growing up queer in a heter-onormative society leaves “a wound caused by exposure to overwhelm-ing shame at an age when you weren’t equipped to cope with it.” If un-processed, this shame lingers – not necessarily as shame about being queer, but as a deeply rooted conviction that one is somehow unworthy, unlovable, or fundamentally flawed. When our identities are repeatedly invalidated by the world around us, our senses of selves become frac-tured. Books and stories have shaped my psyche and identity as a young queer man. They helped me to rebuild this sense of self. I want to acknowledge some of the writers who, through the unapologetic power of the first per-son, shaped the

Hugo I am today – the one who is so far from the boy who once wrote he’d rather be dead than who he is, now writing these very words. Here is a non-exhaustive list of the writers who dared to say “I” and who enabled me to do so, too. I am thinking of Audre Lorde. As a self-described “Black, lesbian, mother, warrior, poet,” she tells us about the women who have shaped her life in Zami: A New Spelling of My Name. Lorde writes about her friends and lovers, about Bea, about Muriel, about Lynn, about Afrekete. She told us about lesbian sex, about care, about the abortion she had to undertake. She curates a life for herself in which networks of care and political organization are, and remain, at the center. I read her words as I joined my first queer activist circle,

and as I learned what it means to organize learned what it means to organize and use the body as a political and social means.

Close to the Knives, David Wojnaworicz recounts his violent childhood, his homelessness, his friends, his sex work, and the AIDS crisis. He finds fragments of beauty in violence without ever romanticizing them. He challenges us to examine our lives – politically, socially, emotionally, aesthetically. He reminds us: “Smell the flowers while you can.” I try to.

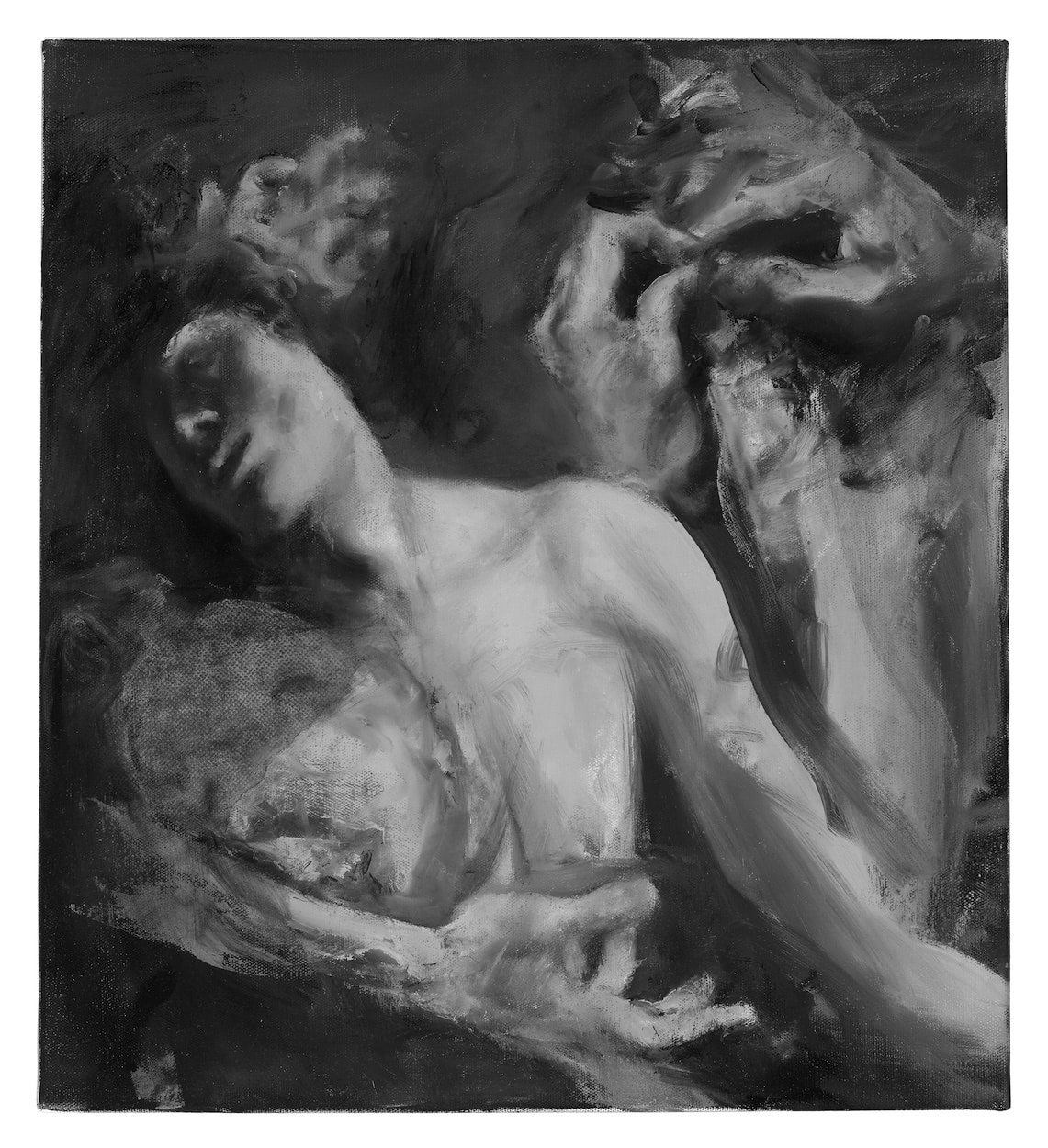

This image immediately evokes the vivid intensity of Carmen Maria Machado’s short stories. In Her Body and Other Parties, she translates into words what it

“WHEN OUR IDENTITIES ARE REPEATEDLY INVALIDATED BY THE WORLD AROUND US, OUR SENSES OF SELVES BECOME FRACTURED.”

means to embody the violence of queerness – how desire, power and fear intertwine beneath the skin. In “The Husband Stitch,” her narrator recounts the stories of women in a patriarchal society, lacking agency and becoming nothing more than objects or, if they go against the system, monsters. Parallelly, the woman narrator of the story details her relationship with her husband, how she knew from the moment she saw him she would marry him, to the birth of their son and to their son leaving for college, leaving the wom-an and her husband in the house alone. Her husband eventually unties the ribbon that is constantly around her neck, and her head falls off. Constance Debré tackles this vio-lence differently – more directly, more confrontationally.

Her prose is a razor-sharp declaration of fuck you and I love you in the same breath. She abandoned her legal career, severed ties with the expectations of motherhood, shaved her head, and in Love Me Tender, rewrote the narrative of queerness – not as a revelation, but as a rupture. She let go of posses-sions, people, and imposed values. It was through sex with women that she discovered she could write – realizing, in the process, that most of what she had once held sacred was meaningless. What matters is to live as freely as possible – and to write.

Notes of a Crocodial With, Qiu Mia- join shows how difficult it is to learn how to love properly – in the realm of authenticity. She tells us about a crocodile

who has lived its whole life wearing a human suit, trying to fit into a human-normative society. Despite its desperate longing to connect with its own kind, because all other crocodiles also wear human suits, the crocodile can’t be sure that it’s ever met another one for real. She tries, throughout the entire book, to unlearn being a crocodile. This is done through a difficult sen-timentality.

Quite the opposite, and yet dealing with the same unease, in Detransition, Baby, Torry Peters made me laugh. It is clear that Peters has composed the story of her book first and fore-most for the people around her – for her friends, and her community: to show them she loves and understands them by

making fun of them. She depicts transsexuality without pathos and with so much humor and sharpness, for showing the difference between being trans and doing trans, between being gay and being queer, between calling yourself queer and actually embodying queerness. She shows how no intellectu-al take is worth considering if it cannot reach the people it is describing.

STORIES THAT GUIDE US OUT OF SHAME

Who else? Maggie Nelson, perhaps. She opened up the field of possibil-ities of the body and of relationship through the complexities of care, desire and devotion she described in The Argonauts. Documenting the changes operating within herself through her pregnancy in

parallel with the gender transition of her partner, Harry, she embraced a fluidity in-herent use of the “I” that I still live by today.

Derek Jarman, James Baldwin, Guillaume Dustan… The list could go on.

But it doesn’t matter. This isn’t about a list of writers dealing with queerness. This is about understand-ing that the books of others have helped me to go from wanting to disap-pear, to inhabiting the world on my own terms. It isn’t about getting rid of the shame – one probably never does. It is about understanding its extent, its subtlety, and understanding it is felt and seen and understood by oth-ers through words that wield language as a weapon, a salve, and a map. Our identities and bodies are

shaped by the stories that are told about ourselves, and that we tell in Our identities and bodies are shaped by the stories that are told about ourselves, and that we tell in return. We don’t get to decide which ones to live by, but we can try. It is the extent of our fight.

As I write this, right-wing cam-paigns and tech billionaires seek to deny and erase trans lives. The fight is far from over. Let it be informed by words and images. Let’s turn to Paul B. Preciado, Elliott Page, Andrea Lawlor, Akwaeke Emezi. Let’s take to the streets, organize in our communities, and care for each other.

The narratives coming out of it will

guide us inward, forward, and out of shame.

WORDS HUGO SCHEUBLE

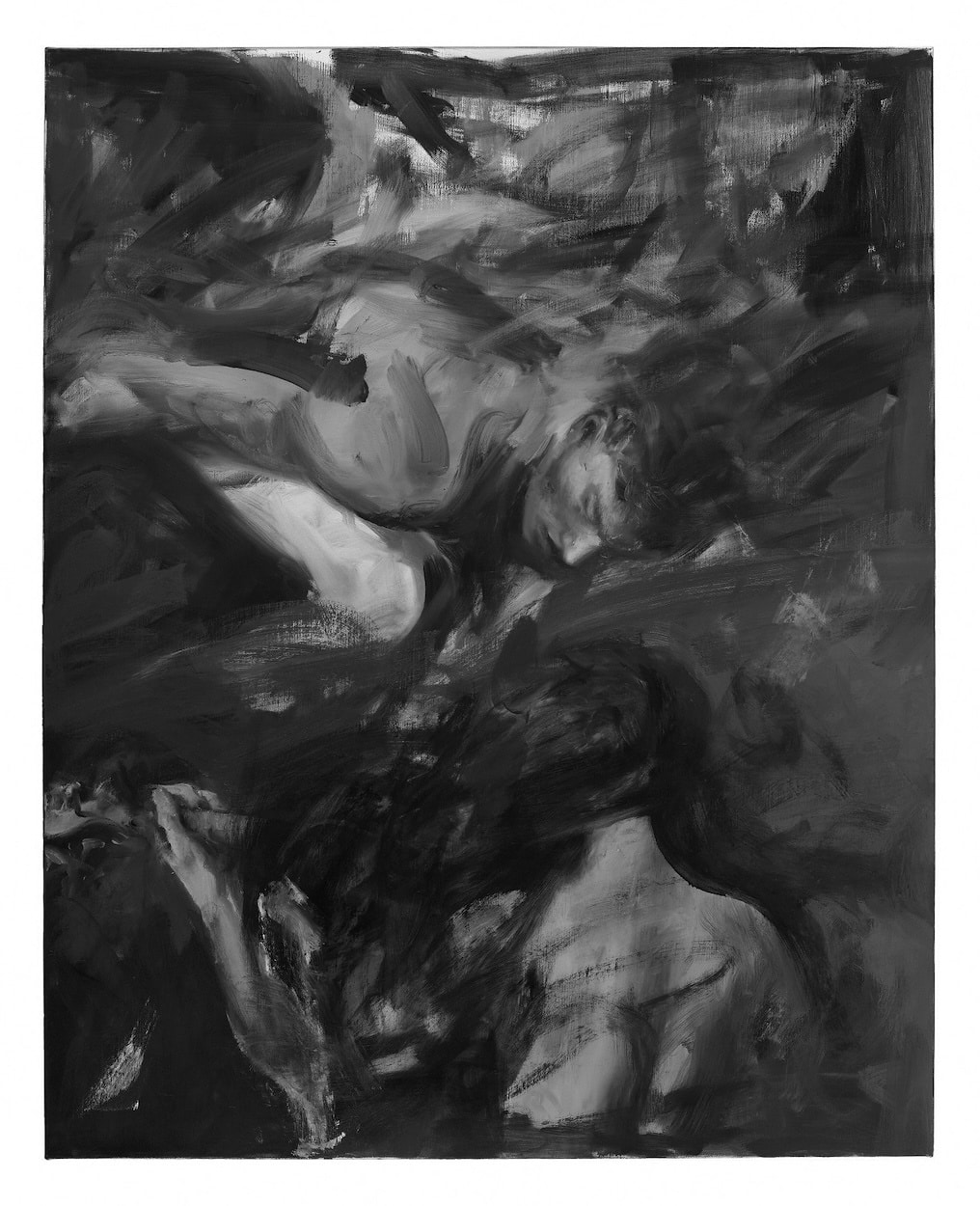

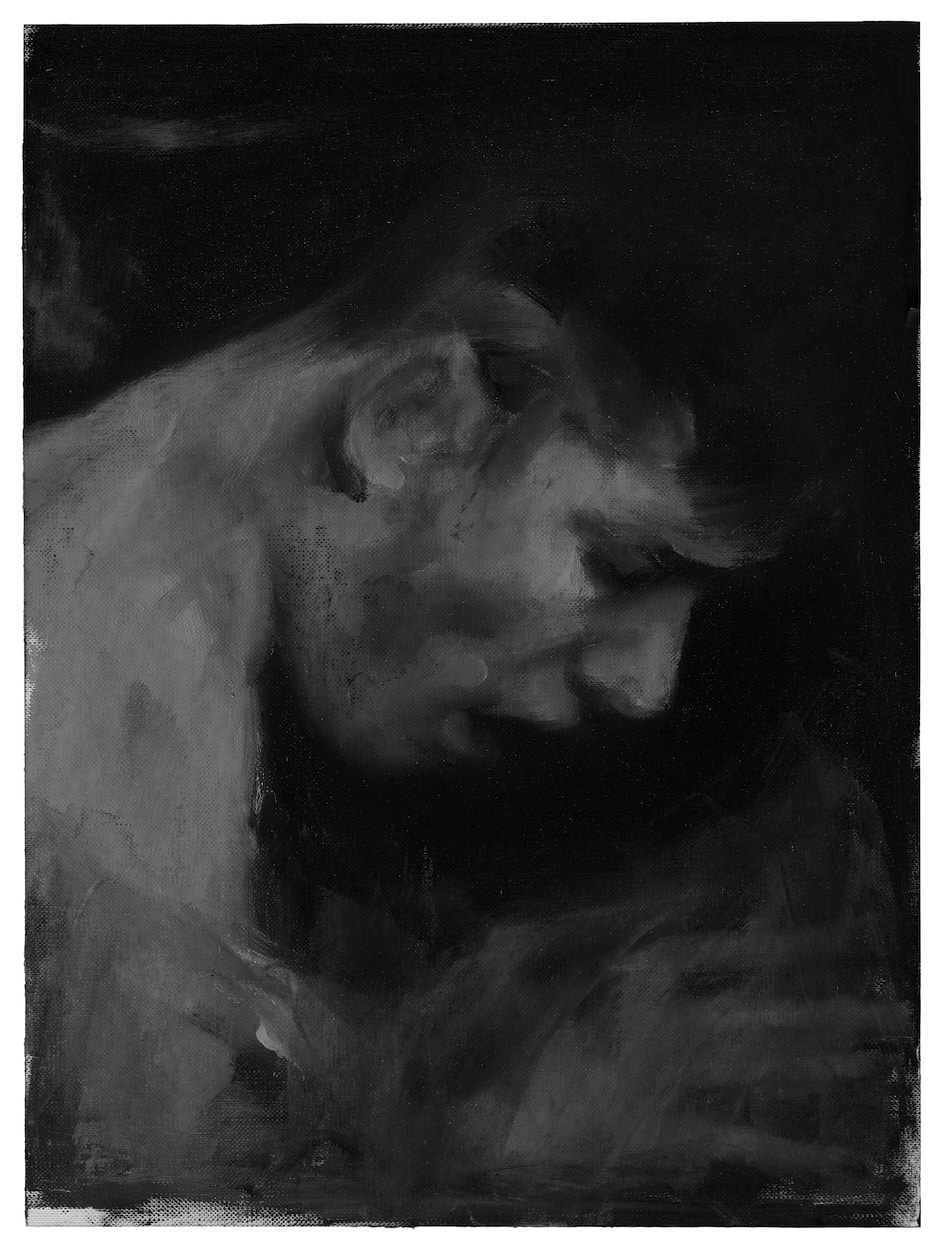

ALL IMAGES COURTSY OF CORNEL BRUDASCU