A NON-EXHAUSTIVE APPRECIATION OF THE I’S THAT HAVE SHAPED MINE

“I WANT TO ACKNOWLEDGE SOME OF THE WRITERS …

Martin Mai: My first real interaction with image-making that went beyond hobby photography happened during a family get-together. I was tasked with documenting the whole thing on Super-8 Film, and it somehow turned out very experimental. I think I was about sixteen at the time. Despite the footage not being very usable as documentation, everyone was fascinated by the result. “You’ve got something there. You have to make something out of it,” is what they told me back then.

So, after graduating from high school, I applied to the University of Essen (Folkwang School). My studies in communication design were actually quite broad, with art history, philosophy, and semantics as theoretical subjects, and painting, drawing, graphic-design and photography in practice. It quickly became clear that my talent lay primarily in photography.

After two years I changed to Istituto Europeo di Design in Milan to finish my studies and started working primarily as a fashion and portrait photographer. However, this desire for classification and categorization of my work always came from outside; I never liked setting those boundaries. Of course, Fashion and Portrait need a different approach and focus, but I’ve always believed that featuring the model’s personality is just as important in fashion photography as a fashion statement is important in portrait photography. But yes, my focus is truly on people – even though architecture and interiors have always played a big role, too. Of course, there are many other reasons why one would choose photography as a career: traveling, meeting people, and seeing places you wouldn’t normally have access to, but my driving force is ultimately the feeling that there are still pictures I have to take.” I think my biggest theme though, which lies at the core of everything – and I don’t want to sound dramatic – is beauty and transience. Perhaps this theme keeps coming up because I lost my sister when I was 16. She was 18. In that moment, I realized how quickly life—even in its most beautiful and vibrant moments—can end. Perhaps that’s why my fascination with beauty is so strong. At the same time, I always feel this sense of impending danger. Beauty is always threatened, be it by time, by fate, or simply by changing circumstances. I’m not just talking about obvious, visual, and certainly not superficial beauty, but beauty in a very comprehensive and, of course, very subjective sense. And there’s this unstoppable urge to document and capture it in my own way. That’s why, for example, I would have difficulty, directing a play.

Exactly, at least no physically tangible one.

Sure. And of course, things and situations that aren’t beautiful also pass away. But then you’re perhaps more willing to accept that.

What you call “after” is actually my “before.” When I want to photograph a person, I spend a lot of time studying their face beforehand, discovering facial features that perhaps haven’t been discovered before, even in people who may have been photographed many times. In this process, my relationship with the person changes, even before I’ve photographed them. Sometimes strangers become familiar to me, or I discover something strange in familiar faces. That’s why, for example, I don’t have a standard light; instead, I always model the light in the moment, trying to figure out what it needs. The challenge then is to capture these aspects on “film”.

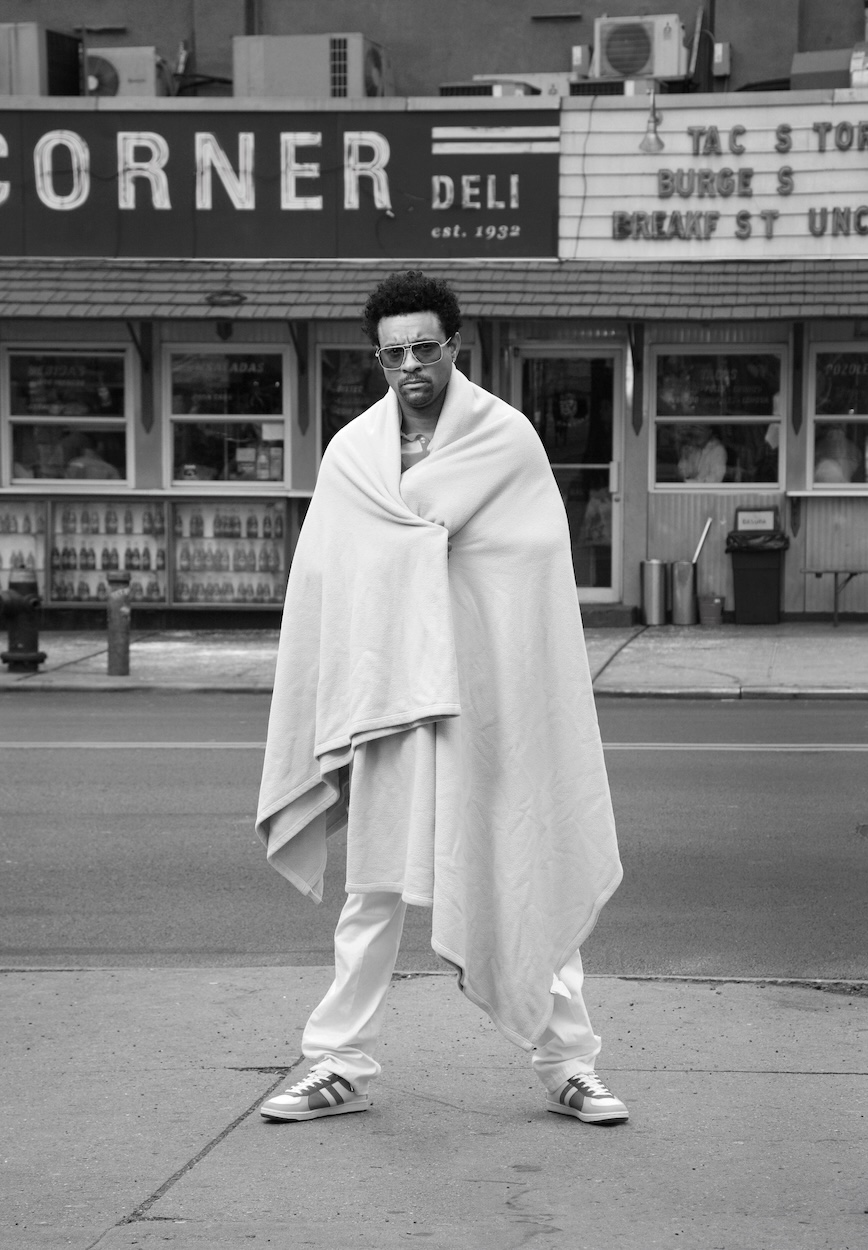

I met Armin last year when I photographed him for another design magazine. We immediately sensed a special connection between us. We met a few times, became friends, and the idea of making a film portrait of him was born, which we’re still working on. We were just finishing a day of filming in his studio when Numéro asked me to portray him for the Fight issue. There was no briefing, only that it had to be black and white. So Armin and I decided to simply throw away all boundaries and sense of caution. I think that only worked because we already knew and trusted each other. This trust enabled us to be very radical. The traces of his injuries are, of course, very obvious on Armin. The question is how to deal with them as a photographer. Armin already explained his perspective on this in the interview. For me it was important not to have a voyeuristic view, nor did I want it to appear exhibitionistic. We ended up taking almost 30 pictures, and in the end, we only removed two. One because it was too banal, and the other because there wasn’t enough justification for showing it. I think there are already many intelligent interpretations and classifications of Armin’s work, and I don’t want to join in on that now. What has changed for me though after these days is that I feel I intuitively understood his paintings and driving force much better. What connects us, I think, is a sense of urgency that underlies our work.

Right – and if that’s the case, then every image, every photo has its justification. Whether you say you like it or not. Because if that’s your motivation, if it comes from you, then you’re in a sense unassailable. That doesn’t mean you’re incorrigible. But you can stand by what you do, no matter what others say.

Yes, but honesty not in the sense of being fact-based; that would be too much of a limit in creating art. I would perhaps rather speak of truthfulness regarding one’s own concerns and intentions.

Fantastic. I never felt the need to add color to these photos.

Taking a picture is always about that “magical moment.” Everything comes together in that one moment, regardless of whether it’s “caught” or staged.

At some point, I felt the need to tell my stories in a different way. But film, of course, requires a completely different approach. You can photograph alone or in a small team if necessary. But in filmmaking, I had to learn to redistribute tasks. I had to learn to trust others.

Yes, it starts with an idea that becomes a script. At some point, the actress or actor reads the script aloud, and it comes to life. On set, lighting, costumes, location, acting, and staging come together; in the postproduction the music and editing—it’s an incredibly beautiful process, how things come together, how the individual layers create something amazing, to which so many people contribute.

In 2021, I shot my first feature film in Ireland—not as a director, but as a DOP. I had no experience with the processes on such a large film set. But the director just told me, “Don’t worry. On set, I actually had complete freedom to do it my way, and the director ultimately got the images he wanted. The film, by the way, won many awards at international festivals.

I would describe it more as a vague feeling. It’s not like I have a stack of images I’m working through. Nevertheless, there are of course specific topics that interest me and that I’m working on. A long-term project of mine is photographing crying women. In a moment of fragility, a face has so many facets, it’s very fascinating. It’s not that I am striving to create a documentation of women in distress—quite the opposite. I think allowing and showing vulnerability is a great strength. And for me, it’s also about showing this incredible strength. The process often exhausts me as much as it exhausts them. But it holds the potential of creating very iconic Portraits.

“I WANT TO ACKNOWLEDGE SOME OF THE WRITERS …

A day after he played at the Live From Earth Festival in Berlin, we met German producer…

Desigual Studio transforms the brand’s DNA with premium materials, craftsmanship, and…