“For me it always mattered that my work exists in a public domain and there is a reaction to it”

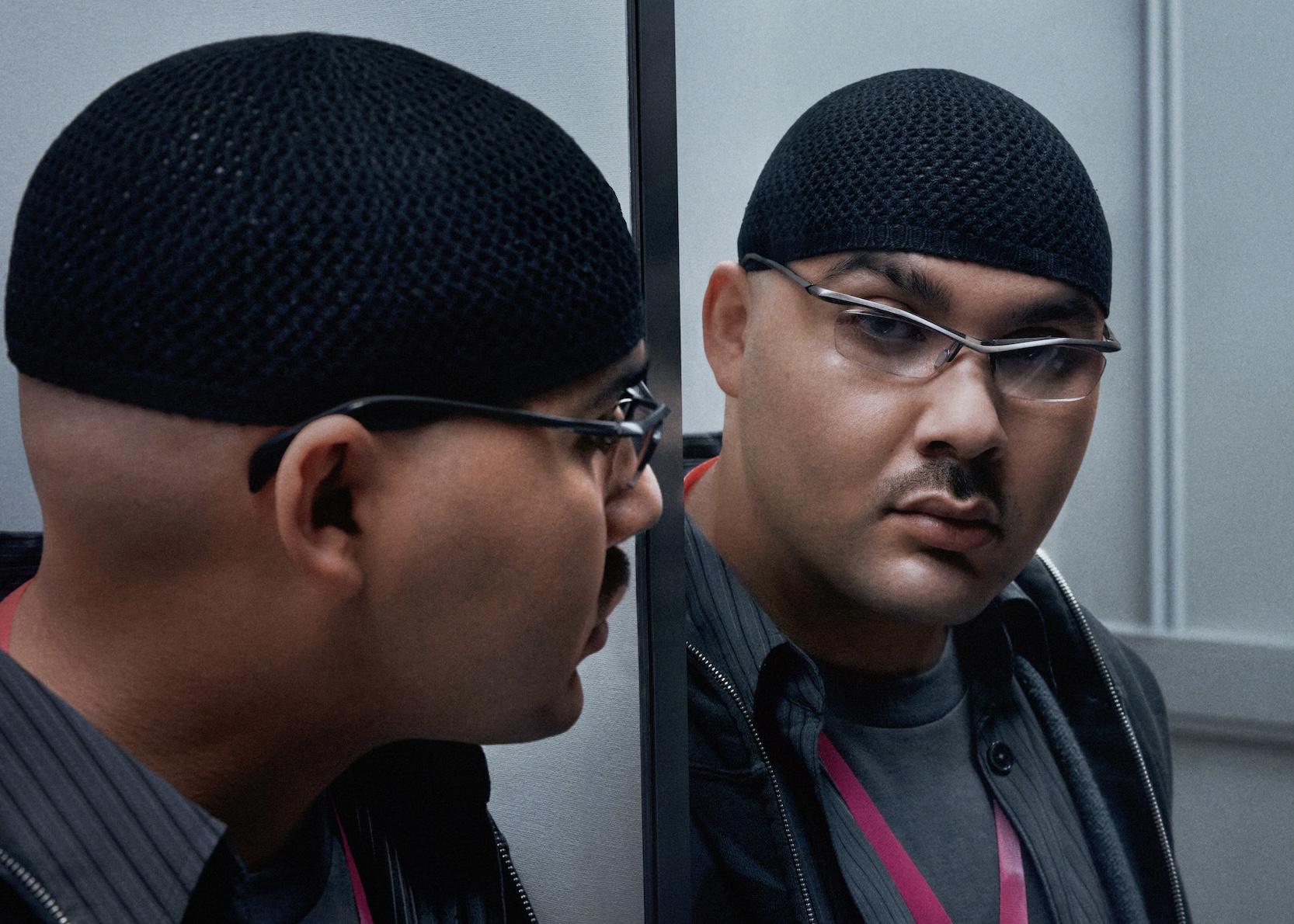

The day before we met Mechatok in Berlin, he played at the Live From Earth Festival, where hundreds of young people came together and celebrated on what was, for this summer, an unusually beautiful Sunday. Mechatok is a producer and released his debut album Wide Awake one month ago, featuring collaborations with Bladee and Ecco2k. I spoke with Timur Tokdemir — orignially from Munich and now based in London — about the importance of creative exchange and his experience in our shared hometown, the differences between producing music in London and Berlin, and his background in design.

Mechatok: Honestly, I think I spent most of my time on my laptop speaking to people on Facebook and SoundCloud. There were a few things quite sporadically that really mattered. For example my friend Alberto Troia, a visual artist, was throwing sort of like after-parties for gallery openings at “Kunstverein” and always brought out really interesting artists. That had a big impact on me in Munich. And then there was a club called “Kong” that closed I think six or seven years ago, that place was really good. And I really like the Public Possession guys, we did a record in 2015. I think that was what Munich really did for me. But it was a lot of just being in your bedroom and being on the laptop, honestly.

The album wasn’t so much about purely being trapped in some online loop, it was more about the contrast of doing that while existing in this now very imperfect and stressful reality. I mean at least that’s my personal experience, you know, like living in some shoebox apartment in London, having very stressful commutes and things just being very hectic and imperfect. And then you look at these glossy things on your phone that look sparkly and perfect.

“That discrepancy, that tangent between those two spaces is what the record tried to capture”

So you probably hear it with these very crystalline and almost clinical synth sounds and then all these samples and quite rough voice notes and stuff. That’s kind of the picture I was trying to paint I think.

It was super formative when I was a young teenager but it’s funny because in the recent couple of years music has become a lot more real life based. I think going to London really changed that because making music there is a lot more of a social thing, because there’s a studio culture where everyone’s in the same basement meeting each other. Whereas in Berlin for me the social aspect of music was always very much going out and partying. That’s where you meet people, but making music was something everyone does at home on their own. So the internet stopped being the main place to exchange everything, which is cool. I’m glad it became a bit more physical in a way.

Honestly, it feels really good because I think the numbers thing can make you really insecure. Because there’s so many factors that affect how these numbers look, you know? It might be like the time of day that you post something or whatever, so what’s really good about real-life shows is that people pulled up and they clearly have a very immediate reaction to the music so it’s definitely reassuring.

Probably around like 16, 17 or something. It’s not that I didn’t enjoy doing that, it was more that the reality of how that would look is so different. It’s not like violin where you can just be in a big orchestra. Classical guitar is a quite particular thing and that world felt very conservative. It almost reminded me of sports, where people train 10 hours a day and then the rest of their interest is actually super basic. It’s almost like they’re not into art. It just doesn’t feel like there’s a larger interest in culture. It’s more, just sort of athletic, getting really good at doing this one thing.

I think in Munich I was really like that typical teenage bedroom producer, where everything is in your head and you just dream up a world for yourself and communicate it online, but it’s all very imaginary you know. And Berlin really made me rooted in the club, I mean that’s to be expected haha. I was deejaying at OHM like literally every other Friday before it was so popular, now it’s so hard to ever have a party there. In Amsterdam I did my masters in design and fine arts. There things became very conceptual and theoretical and I was reading a lot and thinking a lot. Rather than making original music all the time, I was more working on sound installations and producing other people’s records. Then London was like laser focus on music, just being locked into the studio sitting there all night long writing an album.

Absolutely. I mean, it is so competitive. Obviously it’s an expensive city and you have to make things work so you just have to grind. But also if you see people coming up with new micro-genres left and right and new asthetics for their party flyers like every other week, you just feel a little competitive and you’re like, I want to be contributing something that feels as fresh or as absurd or whatever. So yes, I would agree with that.

I have to find out how to deal with that, to be honest, because I haven’t taken a break in… the entire process of making the record, and now I’m touring and promoting the record. It’s just sort of snowballing, the more you do the more doors open so it’s just more work. And I’m still probably used to the times where anything you can get, you should grab and do it. But yeah, I’m just finding out how to do that.

So I studied at the Berlin University of the Arts, UdK, and I graduated in Spatial Design actually in the end. So it was sort of like architecture, but less applied architecture. And afterwards, I studied what was called Design at Sandberg Institute in Amsterdam, which is like the master’s department of Rietveld. It was a double degree in fine arts and design and it was basically very research-based. I always thought that was obviously cool and interesting but also a little pretentious.

I have been producing electronic music since I was 16. Throughout the whole university path, I was making music and that was always a bit of an issue. I was definitely not someone that attended every class, I always was a little bit absent from school. I made it work somehow, but I don’t think my teachers really liked me that much. I still feel good about having done it though.

Yeah, working in university followed this sort of assignment-based structure.

“For me it always mattered that my work exists in a public domain and there is a reaction to it. I feel like I always learn the most by just making something and putting it out, exhibiting it, releasing it and seeing how it does and then drawing my conclusions from that”

I don’t like the idea of having one person tell me what they think about it, like that’s just one person’s opinion whereas if you put it out that feels like a way more educational process. I’m kind of a stubborn and annoying student I think, so I did learn a lot but I just love to argue with my teachers.

The project, Mechatok, I mean it is pretty much like an audio-visual project. I have a lot of visual collaborators, but I still do the art direction of all the visuals and a lot of the graphic design is my own. I always view it as a visual project as much as a musical one, I mean for the new record we did five music videos. Both things emerge at the same time so I’ll make the music while I make the visuals. And there’s always movies running on screens while I’m making music. So it really goes hand in hand.

BUFF MECDICAL RESORT: WHERE MEDICINE, INNOVATION AND LUXURY MEET

A New Vision of Health: On a mission to set new standards in preventive and regenerative…

In Conversation with Martin Mai

Numéro Berlin sat down with photographer and film maker Martin Mai to talk about his path…

DESIGUAL STUDIO UNVEILS A NEW ERA OF PREMIUM DESIGN

Desigual Studio transforms the brand’s DNA with premium materials, craftsmanship, and…

PUMA x NO/FAITH STUDIOS: In Conversation with Leon & Luis Dobbelgarten

"You don't really see that kind of hype anymore"

FLY WITH IM MEN at Andreas Murkudis

During Berlin Art Week, Andreas Murkudis presents in his concept store FLY WITH IM MEN, an…

WEEKEND MUSIC PT. 65: IN CONVERSATION WITH NILS KEPPEL

For their “Weekend Music Tip”, Número Berlin (Ellie & Cosima) spoke to Nils about his…