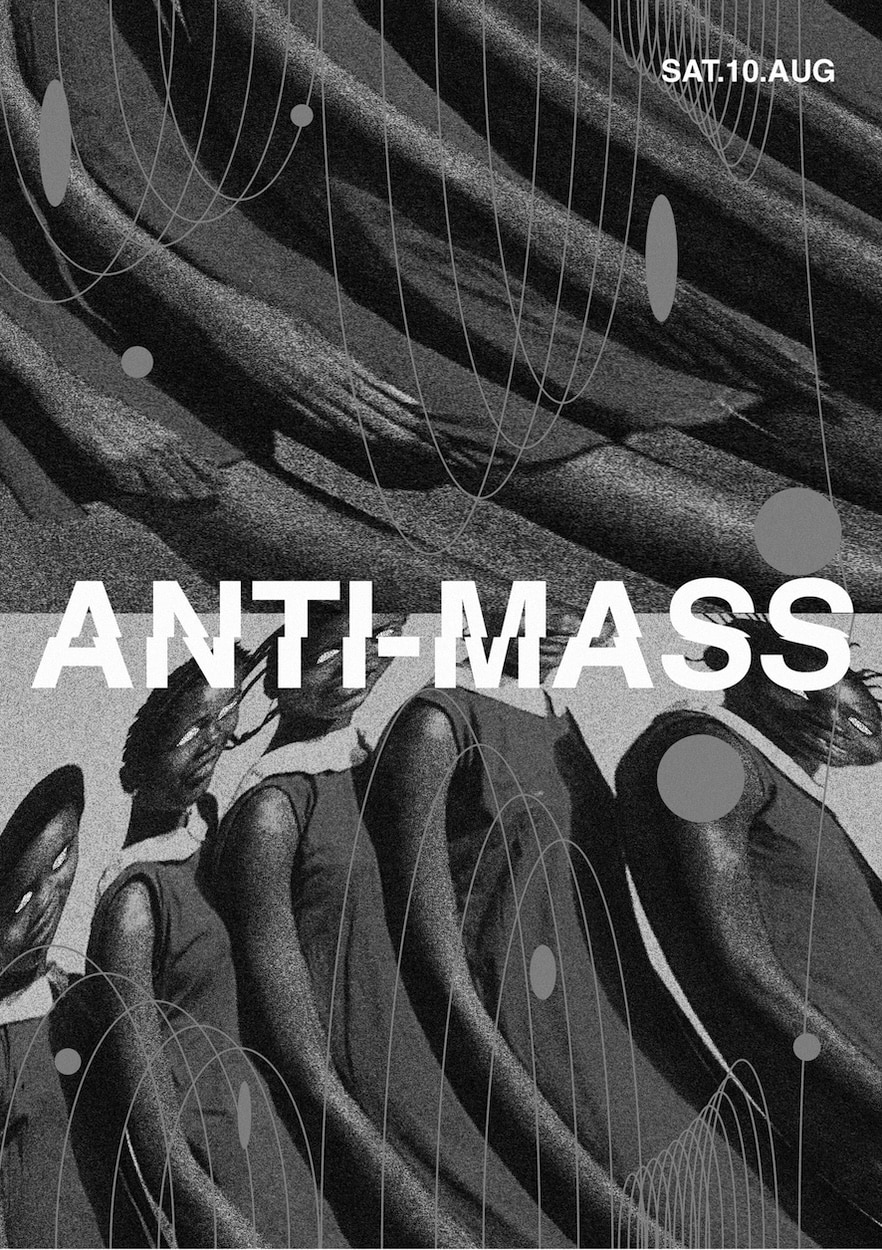

ANTI-MASS is more than a collective – it’s a lifeline, a space where safety, expression, creativity, and community converge. Born out of Kampala’s nightlife, it began as small house parties among friends, later spilling into rooftops, abandoned bars, and makeshift venues. What started as a way to escape Kampala’s rigid and homogeneous club culture evolved into a movement: a refuge for queer bodies, a celebration of joy as resistance, and a platform for experimentation. In a recent conversation with three of the collective’s founding members – producer and DJ Authentically Plastic, multidisciplinary artist Gerald Odell, and producer and DJ Nsasi – they reflected on the origins and growth of ANTI-MASS. Each brings their own perspective, shaped by experiences of navigating queer life in Kampala and beyond. They describe a nightlife scene constrained by class and gender, where genuine connection and freedom of movement were rare. ANTI-MASS emerged as a response to the void of being otherwise; it created spaces where queer people could feel safe, visible, and free to express themselves. But safety is fragile. The passage of Uganda’s Anti-Homosexuality Act in 2023 has made it nearly impossible for queer communities to gather. Raids, evictions and violence have forced the collective to shift its focus from hosting events to mere survival and mutual support. Resistance now takes the form of care – fundraising for those displaced by violence, providing aid within their networks, and finding ways to endure. Yet this survival hasn’t stifled creativity. Art and music remain vital tools for processing, resisting, and imagining a future. For the members of ANTI-MASS, the club and its music remain deeply transformative. It is a place where the body is liberated and individual self-expression is emphasized, while the dance floor simultaneously becomes a space of both collective release and defiance; it is where guards are dropped and the shared energy fosters joy. But their art is also a tool to navigate displacement and a way to sustain the relationships that hold their community together. ANTI-MASS stands as a testament to the beauty and joy that creativity can bring to our life, and also the resilience of queer existence under rigorous oppression. It’s a story of finding refuge in movement, sound and connection – a reminder that even in the harshest conditions, community and expression can survive and flourish.

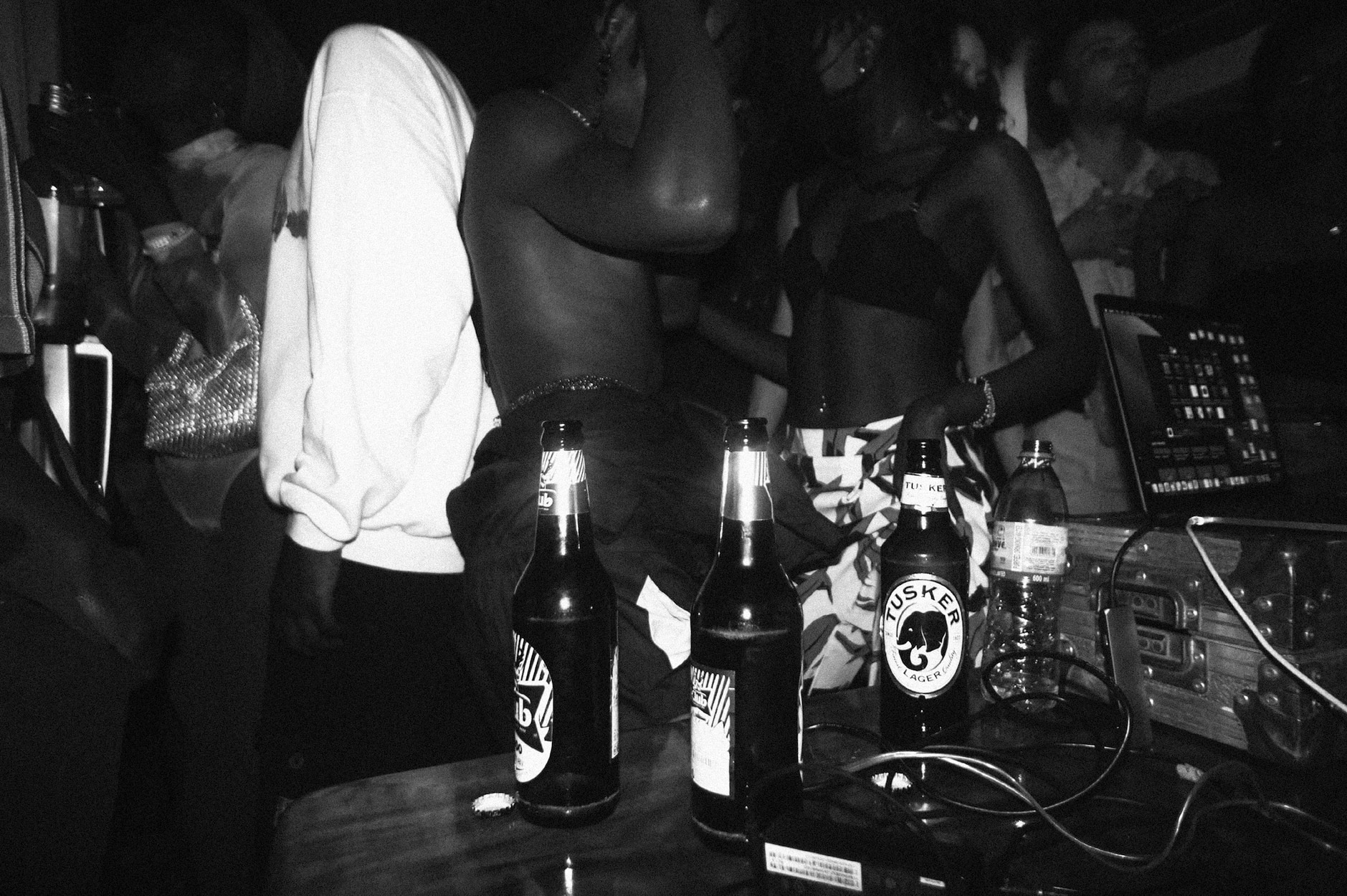

AUTHENTICALLY PLASTIC The collective started with us going to parties and festivals in Kampala. Out of that, we decided to start curating our own nights, which initially began as house parties at friends’ homes – like Gerald’s. But we eventually got tired of being restricted to house parties in domestic spaces. We wanted to extend ourselves and our experiences into the world, not just huddle in houses.

So we started moving to venues run by friends. Our first events were on a rooftop in Nsambya, which is on the edge of Kampala. It was close to the city but still quiet and not very active, which was perfect. One of our main considerations when choosing spaces was privacy – we wanted locations where people could enter discreetly. We had two events there before moving on to other spaces, including a run-down former Congolese bar in the suburbs. Over time, the events kept moving to different locations.

I think part of the reason we kept moving was a subconscious response to safety concerns. Many of us had experienced the raid on Rumba, the oldest gay bar in Kampala, and without consciously planning it, we started adopting security measures – like not staying in one spot too long.

GERALD ODELL We also had this shared vision of what we wanted in a party space. We were always going out in Kampala, looking for enjoyment, but we’d come back feeling like something was missing. The nightlife in Kampala is often dictated by class and gender dynamics. Men sit and buy the drinks while women dance to please them. It’s very much a lounge culture – people aren’t really dancing. The music is mellow, and everyone’s just lounging, like they’ve all taken a gummy and decided to relax. We wanted something with more energy.

AP Exactly. The spaces felt very performative. Tables were arranged so everyone could see who was walking in, like it was all about being observed rather than enjoying yourself. It wasn’t like a real club experience where you’re bumping into people at the bar or on the dance floor.

GO Right, it’s all about being seen. While it can be enjoyable to observe, it becomes monotonous. It felt like such a waste of potential. We wanted to create something dynamic, with interactions that felt unexpected and alive.

NSASI We also wanted a space where we had control – over the music, the safety, and the vibe. Safety was our primary concern, but musical experimentation quickly became a focus. We could control the lineups and who came into the space. Being queer in Kampala, we often felt out of place in other venues, even those marketed as inclusive. We wanted to create a space for ourselves and our community – one that felt safe but also joyful and celebratory.

AP House parties were restrictive because, at the end of the day, it’s someone’s home. While they were hosted by friends who were allies, there was always this pressure to only invite people who felt 100% safe. We wanted to be more adventurous and create a space where we could meet new people—people we don’t know yet. It was about finding a balance between safety and openness. That kind of anonymity – where you’re not specifically known but still feel welcome – is essential to creating a vibrant queer space. It allows for chance encounters that can be truly magical.

GO It also gave us a chance to meet people outside of apps, which is rare for queer folks in Kampala.

AP Yes, exactly.

GO Meeting people at a bar and feeling sexual as a queer person in Kampala is difficult. These events created an opportunity to feel sexy, dress differently, and present yourself in a new way. The music was sexy, too. It created this atmosphere that was liberating and exciting

JBL I think we can all agree that meeting someone in person allows you to experience and understand them in a way that’s much bigger than what happens on an app. Apps erase something essential. I remember the first time I encountered you – it was at Hull Festival in 2022. I had just randomly walked up to this little

AP Even before the Anti-Homosexuality Bill was introduced in 2023, being queer was essentially illegal. The new law just tightened those controls. For me, resistance used to mean existing openly in society as an LGBTQ person, and extending that presence beyond house parties into public spaces. That was resistance – occupying space in the world. But now it feels different. Society feels saturated with contempt for queer identity.

Currently, my focus is on survival and looking out for our immediate community. Every week, we hear about friends being attacked or evicted. The most urgent need is creating a support system of care—helping each other through crises. When the bill was passed, we raised about £70,000 through donations in Europe and the UK. This money helped people relocate, either internally within Uganda or to places like Kenya or Zimbabwe, and supported trans women with essentials. While it helped some, we can’t evacuate an entire queer population. Violence continues, and we do what we can, working with grassroots organizations like HRAAP, a human rights law group. Resistance now means survival and care more than creating spaces for enjoyment.

In the past, resistance meant daring acts like throwing parties where people dressed up and celebrated freely. There was a time when society’s reaction was more indifferent – people might laugh or judge, but wouldn’t necessarily report you or attack you. That window has closed.

N For me, resistance is about resilience. It’s important to show up for the community, but relocating has been a personal struggle. Leaving behind a lifetime support system and adapting to a new environment is challenging. Resistance right now means building a new life—finding networks, continuing my music, and setting up in a new place. While we’re not organizing massive parties, we collaborate with other queer collectives in Europe. That’s what resistance looks like for me now.

AP I’m tempted to say resistance includes working on my art and music. While creating music helps me survive personally, I’m reluctant to call it resistance when it exists in isolation. For me, music becomes resistance when it’s tied to events and spaces where queer bodies can move freely and express themselves. Right now, music helps us survive, and we’re still producing together, but it feels disconnected from larger acts of resistance.

GO For me, resistance right now includes surviving my first winter in Germany! On a more serious note, being here has given me a moment of respite, but it’s also made me confront the trauma I’ve been carrying. I didn’t realize how much PTSD I had until I left Uganda and had the space to process it.

I hold onto the belief that change is inevitable, even if it doesn’t happen in our lifetime. It’s like a pendulum – it swings one way, then the other. This isn’t the first time Uganda has enacted policies like this, but it’s the most intense we’ve experienced. Despite the physical separation from each other, our community remains strong. Many have left Kampala, and we’ve had to adjust to living apart, but there’s still a sense of belonging. That connection persists in different ways – through sharing work, helping each other in times of need, and thinking about each other.

For me, resistance is keeping those relationships alive, even when physical communion is impossible. It’s about showing up for each other, continuing to care, and holding onto our sense of community. That’s what keeps us going

GO In Uganda, queer people pose a societal threat because we challenge the rigid image of what a Ugandan man or woman is supposed to be. There’s a heavy investment in this image: Men are supposed to marry women, have children, and uphold traditional roles. There’s no room in that narrative for trans or queer identities. By existing, we disrupt the status quo.

This makes us an easy scapegoat for politicians, who channel societal frustration and anger toward us. They claim we’re the cause of broken families or societal decay, echoing the same talking points used by

performance stage where you were playing and I thought, “Oh my God, this is amazing.” I had such a good dance and was blown away. It was absolutely brilliant. That moment made me think about the political and social importance of club culture for queer communities worldwide. It’s such a privilege to have spaces like Hull Festival and other venues where queer identities can be displayed so openly and celebrated. What do you think it is about the club or nightlife in general that makes it such a safe haven for queer people? Why do so many queer people feel at home in these spaces?

GO I think it’s about the shedding of inhibitions that is possible in club spaces. People tend to let their guard down because they’re focused on enjoyment. That creates an atmosphere where you can feel like part of a community, especially for those of us who are often pushed to the margins of society. In these spaces, there’s a collective energy – whether it’s from the adrenaline, the endorphins, or just the shared sense of joy – that allows people to feel less guarded.

But, unfortunately, these spaces are becoming harder to find, especially in places like Kampala. Politics and social pressures are making it more difficult to maintain these safe havens. For example, one of the oldest queer-friendly bars in Kampala was raided and shut down. That bar was only open on certain nights, like Sunday nights, which everyone knew was “queer night.” After it was raided, people had to find new spaces, but nothing was ever permanent. As soon as the police or property owners found out that queer people were gathering, the space would be shut down. These clubs weren’t just places to dance. They were spaces for respite and community, where we could come together, escape our problems for a while, and be with people who understood what we were going through. Now, even those moments of refuge are shrinking.

AP Yeah, I think the club also provides an opportunity to escape surveillance. Nighttime offers a kind of shield. It allows for anonymity and privacy. That said, it depends on the club. Some clubs in Kampala still feel very surveilled, almost performative, like we mentioned earlier. But when you find the right space – especially one with experimental music – it can be transformative.

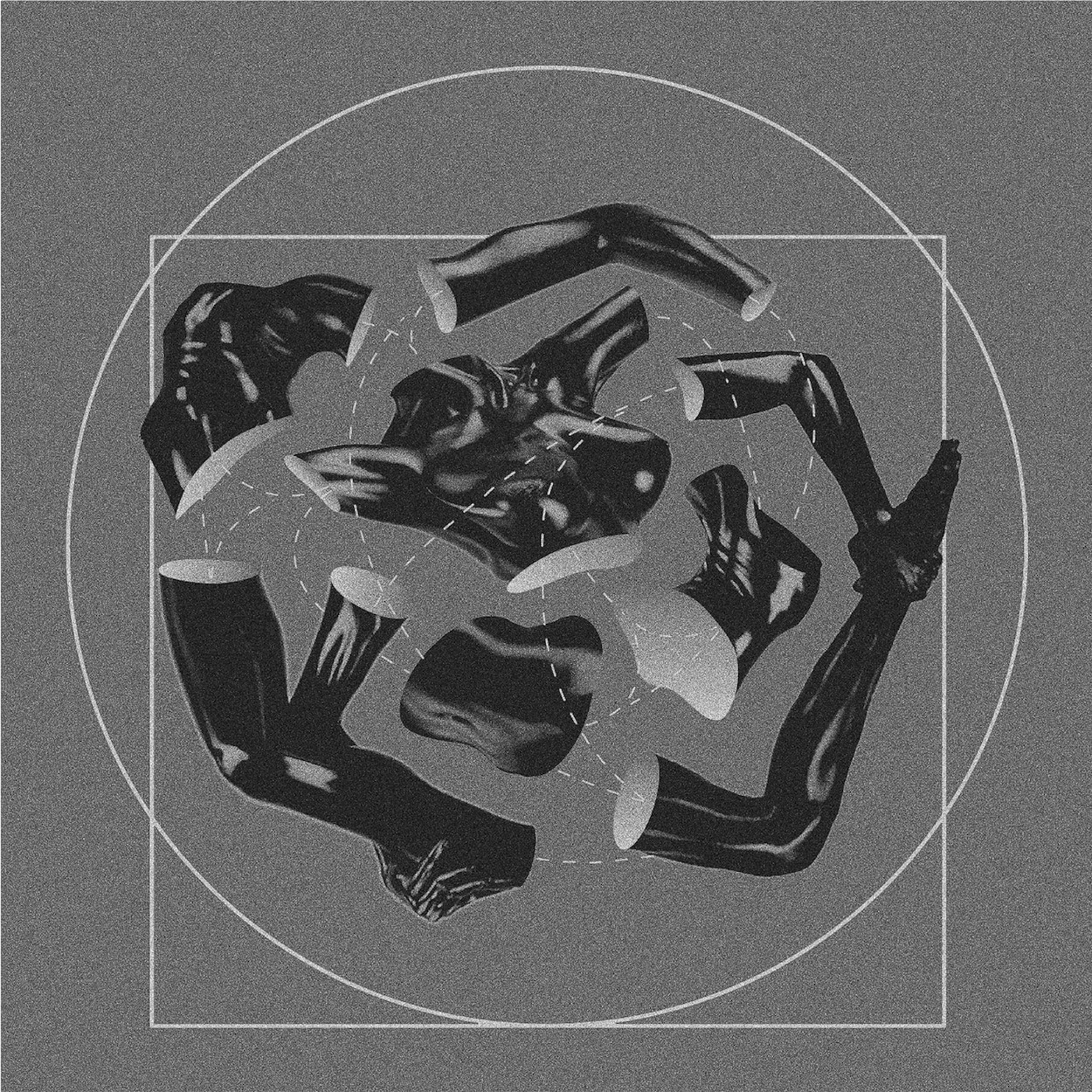

There’s something about weird or unconventional music that feels liberating. When the music is strange or unexpected, it gives people permission to be strange and expressive, too. There’s this unspoken pact between the music and the dancers – an energy exchange that allows for freedom in movement and identity.

N For me, club spaces are about the dance floor. Dance floors bring together people from all kinds of backgrounds and experiences. They allow everyone to connect, revolt, release, and just be. Clubs still offer that sense of freedom, and it’s incredibly important to have those spaces. That’s what I think about when I relate to clubs—they’re spaces for collective expression and joy.

N The law has definitely affected us. It has shrunk the possibilities of gathering as a community. People are trying to stay safe, avoid being seen, and not get into trouble. So, we can’t organize events or parties the way we used to—it’s too much of a security risk, not just for us, but for our community as well.

That said, our collective has shifted its focus. We’re now working to establish relationships beyond Kampala. While we still have an active community back home, we’re not throwing full-on queer parties anymore. Instead, we’re collaborating with other communities and finding new ways to connect and create together. But organizing a big queer event in Kampala right now is just not safe.

GO It’s very layered and complicated. In Uganda, queer people are displaced within their own society. You’re in your home country, but you’re treated as if you don’t belong. Fighting back in that context isn’t straightforward.

American evangelical conservatives. These colonial narratives have been transplanted into the African context. Being a small, unprotected minority without political power makes us an even easier target in a frustrated, corrupt country.

N Yes, we’re a distraction from real issues like corruption, broken systems, and mismanagement. It’s convenient for the government to shift public attention to “the gays” instead of addressing pressing problems. Elections are coming up, and of course, we’re going to be made into a problem again.

AP Yes, I’ve noticed a shift in my work. This year, while creating new material, I found myself drawn to softer, more reflective sounds. It’s likely a response to where I am emotionally – focused on care for myself, my friends, and my community. My earlier work was more aggressive and disorienting, but now I’m exploring stability and repetition, even in dance tracks. It feels like a way to engage with the politics indirectly, rather than opposing it head-on, which can be so exhausting.

N For me, it’s been hard to find the stillness of mind to create freely. I miss the openness of Uganda’s outdoors, the beauty of the landscape and the chaos of Kampala, which used to inspire me. Now, there’s a constant feeling of needing to be safe, even when I’m out. I’m always aware of who’s watching or judging me. That underlying fear makes it difficult to tap into the inspiration I once had. While my sound hasn’t changed much, the sense of safety that used to surround my creative process has.

GO The challenges started before the bill – with the pandemic and its aftermath. COVID-19 created a gap where we couldn’t gather physically, and the economy worsened. Queer people were already being scapegoated when the bill was introduced. For me, these compounding difficulties forced me to pivot multiple times – from a 9-to-5 job to curating and eventually committing to my art practice.

While the bill propelled me further into exploring my artistic process, my inspirations remain the same. As queer people in Uganda, we’ve always been displaced. That sense of displacement, the mythologies we create to survive and galvanize ourselves, continues to inspire my work.

GO It’s both. It depends on the context and the questions that need to be addressed. For us, it’s been less about reclaiming space and more about creating refuge. We’ve always built something from scraps in a society that doesn’t want us, and that in itself is powerful.

AP I agree. Music, for me, can create a sense of connection and belonging. On the dance floor, when the music is playing, we become vibrating, shaking bodies, moving together. Even people who might otherwise judge or oppose us can’t help but join in. I’ve found kinship and familiarity on dance floors, even with people outside the queer community. Our presence has made some parts of the artist community in Kampala more open to queer identities, which feels like progress.

N Yes, dance floors are places where different people come together. Music has a way of creating a shared energy that unites everyone, even if they come with different intentions. I’ve played sets for very straight audiences, and I’ve seen them lose themselves to the music, asking for more. Even in spaces where people come with preconceived notions, music breaks down barriers and fosters understanding. For me, music is definitely a tool for claiming space and resisting.

GO On a fundamental level, art and music are how we live. They’re tools we use to exist in this world in the way we want. Creating with others naturally fosters hope. Someone once told me, “Hope is in the doing.” That resonates with me. Art is essential—not just for survival, but also as a means of building careers and sustaining ourselves.

“IN THE PAST, RESISTANCE MEANT DARING ACTS LIKE THROWING PARTIES WHERE PEOPLE DRESSED UP AND CELEBRATED FREELY. RESISTANCE NOW MEANS SURVIVAL AND CARE MORE THAN CREATING SPACES FOR ENJOYMENT.”

“I HOLD ONTO THE BELIEF THAT CHANGE IS INEVITABLE, EVEN IF IT DOESN’T HAPPEN IN OUR LIFETIME. IT’S LIKE A PENDULUM – IT SWINGS ONE WAY, THEN THE OTHER.”

“DANCE FLOORS BRING TOGETHER PEOPLE FROM ALL KINDS OF BACKGROUNDS AND EXPERIENCES. THEY ALLOW EVERYONE TO CONNECT, REVOLT, RELEASE, AND JUST BE.”

“WE’VE ALWAYS BUILT SOMETHING FROM SCRAPS IN A SOCIETY THAT DOESN’T WANT US, AND THAT IN ITSELF IS POWERFUL.”

“ANTI-MASS STANDS AS A TESTAMENT TO THE BEAUTY AND JOY THAT CREATIVITY CAN BRING TO OUR LIFE, AND ALSO THE RESILIENCE OF QUEER EXISTENCE UNDER RIGOROUS OPPRESSION.”