Glen’s hurt, connected to a difficult childhood with a fundamental Christian dad and his mother’s mental health issues, found a CATHARSIS in the act of BREAKING and RECONSTRUCTING china.

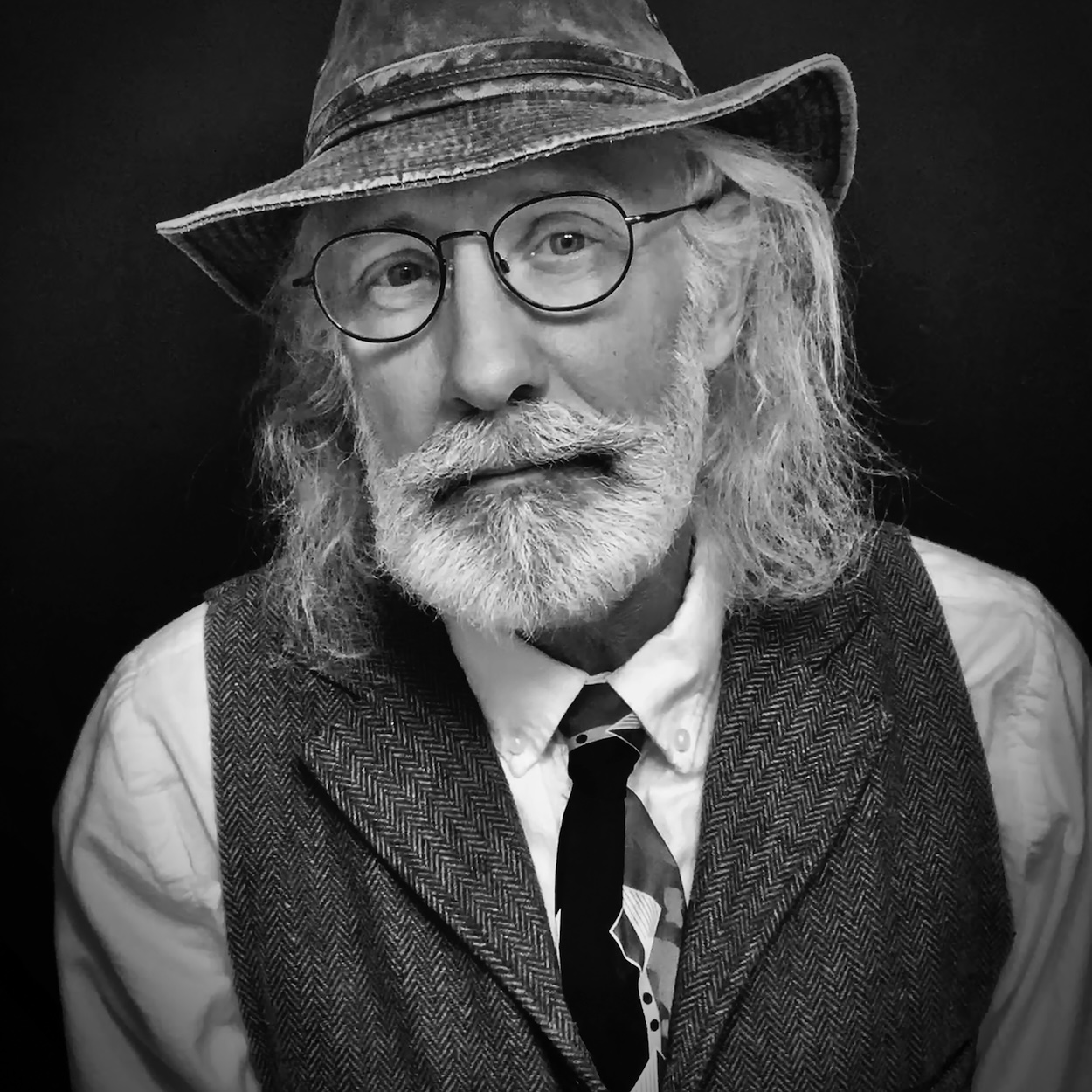

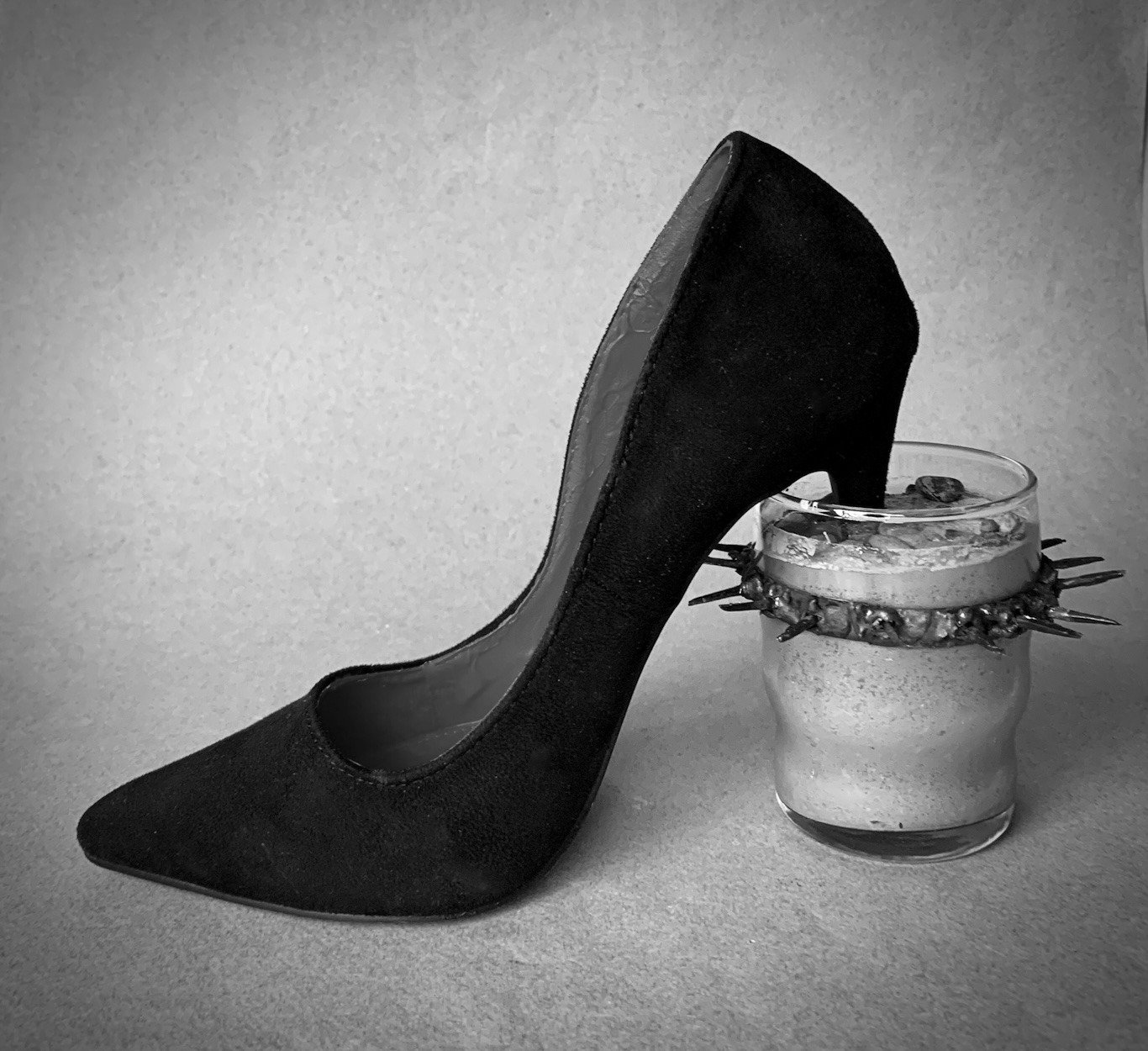

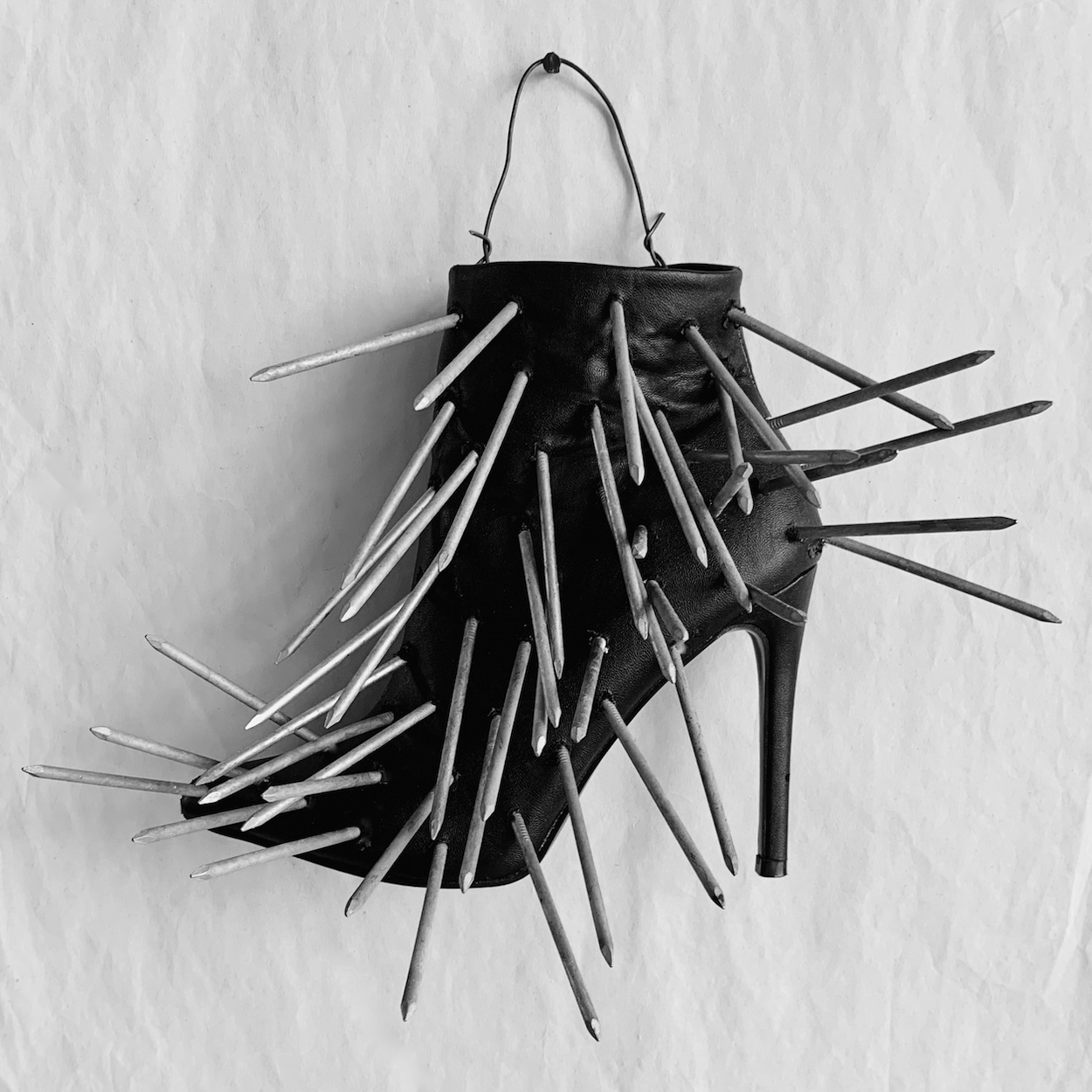

A rusted barbed wire holds a frail piece of porcelain. Worn-out cutlery guards freshly cut edges. We feel a kinship with a toothed tea cup. Glen Martin Taylor’s reimagined tableware hands a bare human heart to the hungry spectators. The kintsugi-inspired, cute-meets cruel artworks call out to our god-shaped holes. At the bottom of them, there’s Glen, transmuting pain. We got the timing mixed up, so I arrived at the digital space of our interview an hour late, apologetic. Glen doesn’t mind: “Waiting is good with me. I’m always creative when I’m waiting.” As in play, the minutes pass but time stops for us as we toss about bits of the sacred and the profane, talk about the art of love and baking bread.

Ohio-based, self-taught artist, originally a painter and, rofessionally, carpenter, he turned to ceramics ten years ago. Despite clay’s traditional meditative perks, he got quickly bored at the pottery wheel. “I was still going through that hard time in my life, and I also knew about kintsugi, which is the Japanese art of repairing broken pottery.” Another post-epiphany discovery came with a box of his grandmother’s dishes. “Nobody in the family wanted them, so I began to break them. And, again, just everything opened up. I realized there were no rules. I could make anything I wanted,” he says. It was paradoxically perfect. Glen’s hurt, connected to a difficult childhood with a fundamental Christian dad and his mother’s mental health issues, found a catharsis in the act of breaking and reconstructing china. “There’s a family, generational healing going on when I’m working with that,” he explains.

Despite his use of hammers, nails and knives, Glen’s fight is exclusive to the canvas of his soul. “I’m a pacifist. I don’t fight other human beings, but I think what I have been fighting is what’s inside of me,” he says, “It’s hard to be a human being, and it’s frustrating. It can lead to some anger, and you fight it.” Glen opened the battlefield of his heart, examining what lurks in the shadows. Years in, the landscape has changed. “I’m a little nervous about giving up the fighting when it comes to my artwork, but I’m learning to find that there’s a lot of other emotions that I can put into my artwork now, as far as peace and self, love and healing and being healed,” he shares. Fighting can become an unlikely ally on the path of pain, and the final one to say farewell

to, often with hesitation. “I’m letting go, and I think we can let go of it eventually. I do think there’s a peacefulness that seems to be the last quest. The last dragon to slay is the fighting of our own self.” Glen’s weapon of choice is radical love – the only force to disarm the violence and grow out of the ashes.

When you lose that child’s play, that’s when men start creating wars, because they’ve lost THE FUCKING JOY OF BEING ALIVE, and they lose their humanity when they become a grown-up.

“We can love everybody else, but the last person we end up loving is ourselves. It took me a long time to realize that.” Even if temporary, the peace is worth it. Many of Glen’s artworks refer to love. One straightforwardly states: “Love is the only answer.” “I don’t think there’s anything more important. I don’t know what else there is besides that.” Overwhelmed with the unnecessary complexities of the everyday, Glen decided to reorder his focus. “I have come to that place where I am just letting go of all those other things that don’t matter because I reached a point of: What are the rules? What the fuck matters in this life?” Reexamining the components, like an alchemist at work, he realized that love is the truest element, whatever love is to each of us.

“As an artist, my job is to express whatever I’m feeling,” Glen states. “I have friends right now that live in Beirut. I have friends who are from Ukraine. I have friends here in the United States.” As he tends to himself against the world’s terror, his purpose is to share the love: “My work is turning more and more to: Can we just love each other? Can we mend? Can we hold each other’s pain? What can we give to each other? And, in the end, it’s some version of love.” This mission directed him to a special kind of mending project when a Ukrainian follower offered to send Glen broken pottery from Ukraine. “Last October 5th, there was a little village called Hroza. Hroza had about 300 villagers, and about 60 of the villagers were at a little cafe having a memorial service, a wake, for one of their soldiers. Somebody let the Russians know, and a Russian missile hit that cafe and killed all 60 people in the cafe, as well as the children in there. I got pottery from that cafe,” he shares. Glen felt the weight of missiles of hatred in each tiny piece of the tragic legacy.

“It’s really overwhelming. You never get numb to humans and their inhumanity to other humans, how cruel human beings can be. You never get used to that.” Taking it all in is perhaps Glen’s most important tribute to the villagers of Hroza, transcending the physical realm of art. There are exhibitions in the planning, with the final one in Kyiv. Glen values this communal distribution of love and understanding. Sharing his heart’s contents with over 175k followers on Instagram, Glen built a community on the reciprocity of healing. Whenever the art touches others and lets them know they’re not alone in their fight, it gives Glen an emotional closure. “As a grown-up, you’re not supposed to be vulnerable. You’re supposed to keep all your feelings inside. You’re not supposed to show any emotions. What’s your deepest fear? Oh, no, don’t tell anybody.

I reached a breaking point where I was like, fuck it. I don’t know what the rules are. I’m gonna go ahead and tell you all the things I’m afraid of. I’m gonna tell you what I’m hurting about,” Glen shares, “I found everybody else on this whole planet is feeling the same stuff. They’re just afraid to say it out loud.” Why are we here? What’s the meaning of our lives? Glen also found himself asking those questions. The answer, or rather a way of living with the questions, came partially from Daoism and Buddhism. Though he values the core goodness of religion, Glen is not one to follow the institutions. “I have problems with organized religion. Religion is founded by human beings and, in a lot of ways, the Christian Church was founded by white men who wanted things their way,” he says. He also reflects on it visually in a sculpture, Toy Clown Monkey on a Barbwire Cross, and incorporates rosaries and crochet crucifixes into his artefacts. “I do admire faith, and I have my own faith. Ultimately, whatever I do, I think the essence of it all begins with some nature of love, but then it gets screwed up with greed and a lot of other stuff and thinking that they’re the one right religion. That’s the scary part. My father thought his religion was the only right one. That’s pretty egocentric to think yours is the only right religion.”

Glen accepts drifting in spiritual uncertainty and confusion, grounding himself in a daily wish to be a good human being, who now knows less than ever before. “Maybe that’s the answer – that we don’t have answers,” he says. “And you find out, over time and with more grey hair, that whatever you think you’re certain about, you probably can’t be certain about.”

He chooses to return to the simpler form of himself, nurturing the inner child within. “I’ve read that there are some Buddhist monasteries where the wisest scholars of Buddhism go at the end of their lives, and they go, and they just play.” Surrendering the traditional knowledge, they immerse in the joy of the present. “Life was pretty nice when you were five years old because you didn’t know anything,” Glen admits.

When you lose that child’s play, that’s when men start creating wars, because they’ve lost THE FUCKING JOY OF BEING ALIVE, and they lose their humanity when they become a grown-up.

Nowadays, Glen lets himself play – not in an adult and sophisticated way, but with the innocence stemming from happy moments in childhood. “I remember there was a rainstorm, and I was allowed to go out behind our garage and play in the mud. I made little mud houses and a little mud castle out of sticks and mud. My childhood was painful, but those moments were cathartic and healing and wonderful and creative,” Glen says. His infectious smile suggests that this play is both silly and serious. It’s a decision to push away the ego notion of success and money. “For me, play means no rules because when children play, they don’t have rules. They just play. They don’t have expectations. I assume every time I start a piece of artwork, it will end up probably in the trash can.” Sometimes, it makes him laugh. Sometimes, it does end up in the bin, which he doesn’t mind. “When you lose that child’s play, that’s when men start creating wars, because they’ve lost the fucking joy of being alive, and they lose their humanity when they become a grown-up,” he states.

Growing up is not an idle game but a never-ending survival camp exposing the inner child to dangerous metaphysical poisons. It’s on us to care for them gently. “Being a grown-up, you accumulate all this heavy crap on you,” Glen admits, “Now that I’m at a point in my life where I’ve really cleaned out a lot of that, I’m allowing so much more love to come my way – not only just love for myself, but also love for other people.”

For Glen, art has been a medium to start the cleanse, a process through which he is learning to rewire previous harmful mental pathways. “I haven’t convinced myself I deserve this much happiness. When you’ve lived in unhappiness for long enough, it becomes familiar. You need to convince yourself that you deserve happiness.” It’s never obvious to the individual that neither the painful childhood nor the abusive relationship was deserved. “I still have moments where I’m like, do I really deserve this much happiness? Yes, I do. I’m allowing that to come in because I’ve made space now by letting all the crappy stuff out. I’ve made space to allow

myself to be happy, finally.” As this positive development expands, Glen wants to show it to everyone else. “I don’t think there’s anything

off-limits as far as what I want to feel. I have expressed some very deep stuff,” he says. The key is the format. Glen’s often palm-size pieces with short, haiku-like statements communicate well with his diverse audience that otherwise could shy away from official art spaces. “A lot of modern art is kind of stuffy and arrogant. I don’t want to reach just a small, tiny art audience. I want to reach other human beings,” Glen says. His art’s purpose is to connect with other human beings, not just art critics.

Recently, Glen found new routes of connection to his family’s past. This time, it’s not about the intricate relations at the dinner table, but the fabric of history of his female ancestors. Glen shows me a wall filled with human-size warrior dresses, vaguely inspired by antique Chinese armor, made from ceramic tiles, leather, and textiles held together by a tangerine wire. Even through FaceTime, they’re breathtaking. It’s a celebration of Glen’s female forebears, extending a few generations down the family tree. The dresses emanate tender strength passed down with the feminine: his grandmother was a beloved woman with 11 children who got up every morning at 5 am to bake bread; his great-grandmother had six children, and her husband died when she was about 40. She carried on, just like many others post-war, raising the next generation on her own. “She did it all with love and tenderness, but incredible strength, when you think about it,” Glen says.

“I especially think that nowadays, we really need to try to appreciate the strength of women. We could certainly use more of that tender strength,” Glen admits. The warrior dresses project honors the past female figures and the modern women in Glen’s life – his daughters and granddaughters.

It’s natural to mythologize artists and even easier with 24/7 access to their curated media feeds. In between the ceramics, Glen allows visitors glimpses of his private life, sharing snapshots of youth, travels and food. “I’m also Glen, and I’m a grandpa, and I’m a father, and I’m a friend. I am a lot of other things. In some ways, showing a little insight into baking bread, a pizza, or something like that is just a way of saying: I’m just Glen. I’m a person.”

With the aid of corroded metal and engraved words, Glen puts the pieces of himself into place. As every part is in flux, the rituals repeat daily. By removing a piece, he peeks inside, and if the inside peeks back – so be it. “The Austrian writer, Rilke, said: Feel everything. I’m paraphrasing, but go ahead and feel all of it. And nothing’s final.” Living with ourselves and others in this ordained madness that we enter with our first breath is tricky. The funny part is that understanding its basic mechanisms requires years of graft, burning away presumptions, and maneuvering away from self-set traps to arrive, scorched, at humanity.

“About five years ago, my older sister got cancer, and it was terminal. She had had a very difficult life, and it wore her out. She wasn’t into fighting the cancer, she was letting go. In one of our last conversations, she told me: ‘All I ever wanted was to be loved.’ She had been married four times. As I carry that, I realize that it’s true for 8 billion people on the planet. We all just want to be loved.”

The allure of Glen’s art is quite simple, actually. Those are everyday objects, a cup, a plate, a knife, that Glen the person poured bits of his soul on, and since our souls are made from the same matter, we see ourselves in them. At first, we might not recognize the image as it’s not what we see in a mirror. This is us from beneath the silver layer, stripped back. The image might be distorted, rusted, and a little strange, but what matters is that it’s true. Love it. Love yourself.

Everything opened up. I realized there were NO RULES. I could make anything I wanted.

I do think there’s a peacefulness that seems to be the last quest. The last dragon to slay is the fighting of our OWN SELF.

I’ve made space to ALLOW MYSELF to be happy, finally.

TO WATCH: “MARTY SUPREME BY JOSH SAFDIE

"I have a purpose. And if you think that's some sort of blessing, it's not. It means I…

TO WATCH: “SOULEYMAN’S STORY” BY BORIS LOJKINE

A man trapped in a system that only values humanity when it can be used

TO WATCH: “NO OTHER CHOICE” BY PARK CHAN-WOOK

No Other Choice is not about losing a job, but about losing the self in a system that…

“I’VE MISSED OUR CONVERSATIONS” AT SCHLACHTER 151

I’ve Missed Our Conversations examines how artificial intelligence is reshaping emotion…

TO WATCH: “IMPATIENCE OF THE HEART” BY LAURO CRESS

The more Isaac tries to help, the clearer it becomes how thin the line is between care,…

TO WATCH: “A WORLD GONE MAD. THE WAR DIARIES OF ASTRID LINDGREN.” BY WILFRIED HAUKE

"If happiness is to last, it must come from within, not from someone else."