A PRINTED PAGE DOESN’T DISAPPEAR WHEN YOU SCROLL PAST IT. IT STAYS. IT INSISTS ON BEING SEEN. IT’S A KIND OF RESISTANCE—AGAINST DISAPPEARANCE, AGAINST FORGETTING.

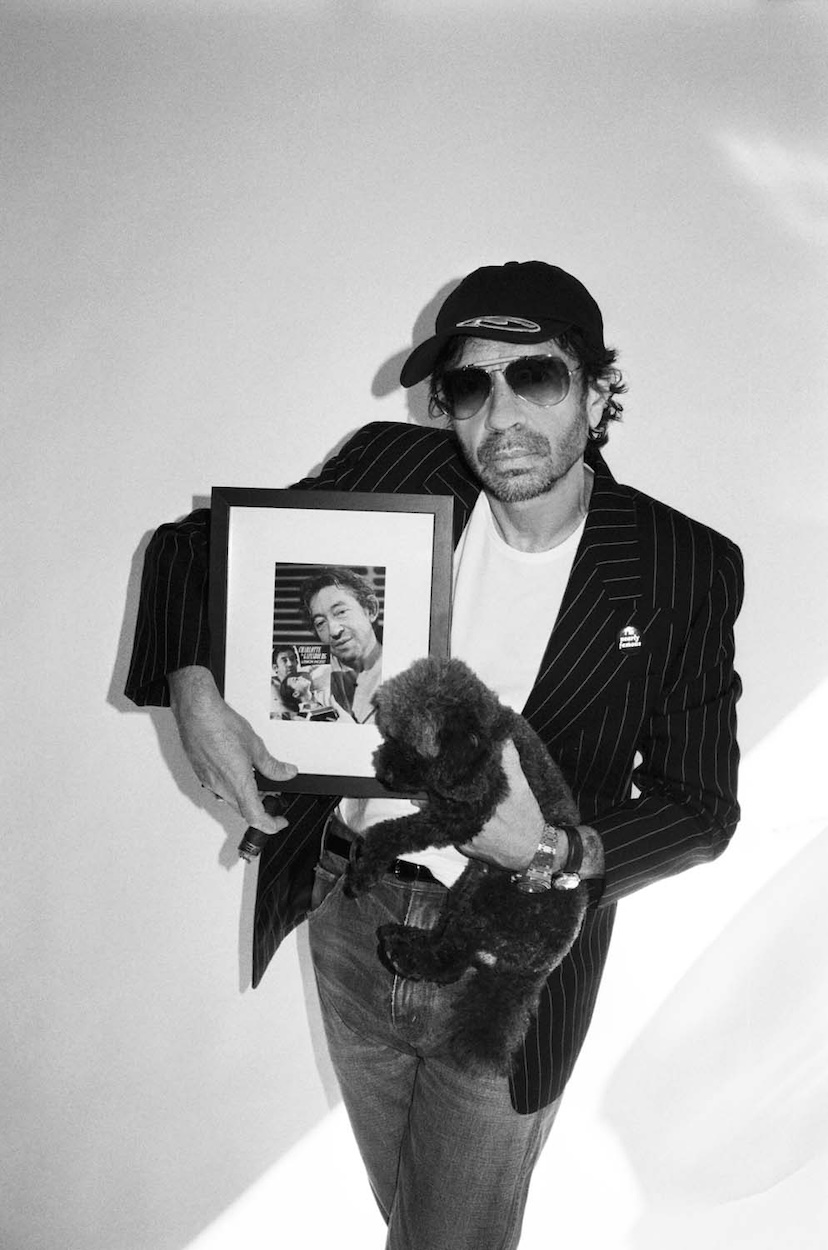

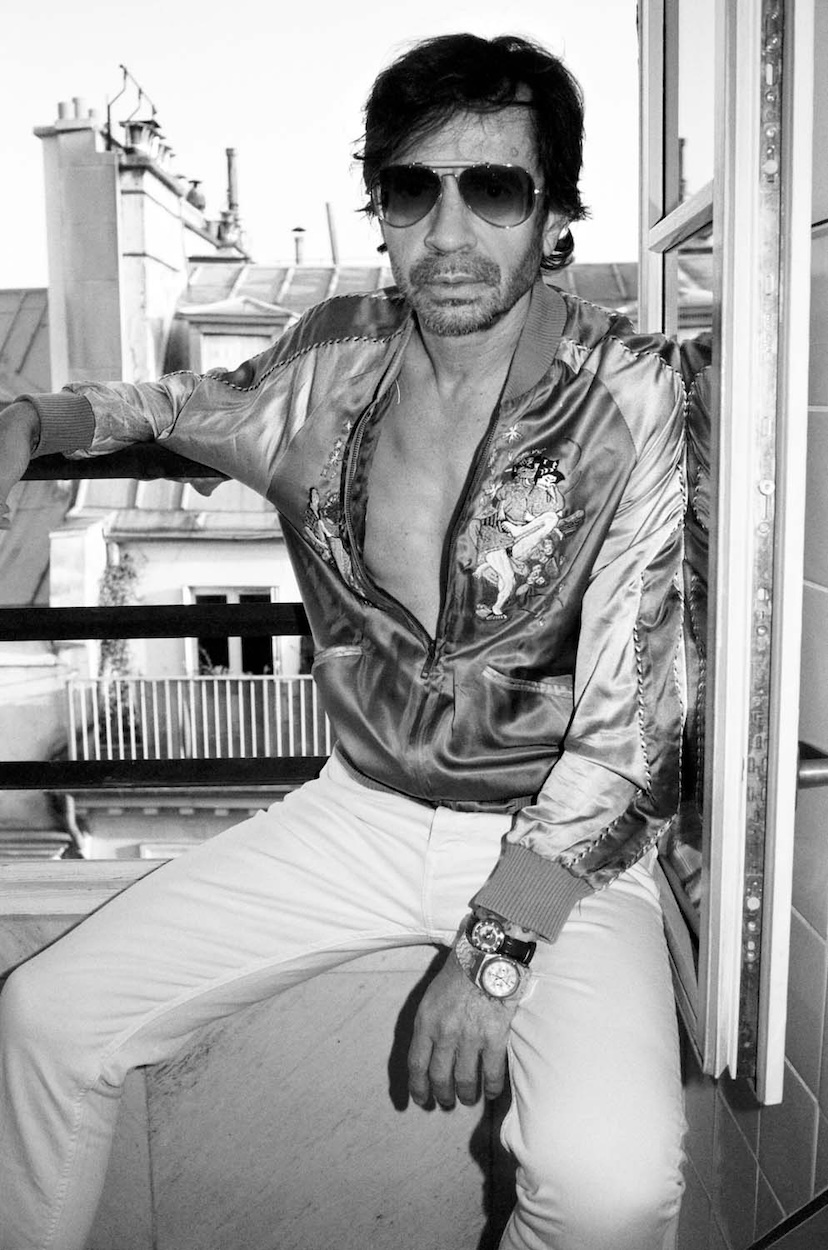

For over three decades, Olivier Zahm has shaped the cultural landscape of independent publishing. As the founder and editor-in-chief of Purple Fashion Magazine, his vision has consistently pushed boundaries – merging art, fashion, photography, and radical thought into a singular voice that feels both avant-garde and intimately personal. In this expansive conversation with Numéro Berlin, Zahm reflects on the legacy of underground publishing, the creative responsibilities of magazine-making, and the challenges of staying true to a vision in an increasingly digitized world. This is a testament to the power of collective creativity, editorial integrity, and the pursuit of beauty as a political act.

TODAY, WE FOLLOW A SCREEN. WE DON’T LOOK AT THE LANDSCAPE ANYMORE. TAXI DRIVERS DON’T KNOW THEIR CITIES. LOVERS DON’T KNOW THEIR BODIES. WE NEED TO RECLAIM SPACE. REAL SPACE.

Olivier Zahm: Absolutely. Doing a magazine was always my main focus. When I was younger, I wanted to be either a photographer, filmmaker, or writer. In the end, making a magazine allowed me to do all of these things at once, without being confined to just one. I was never going to be a successful filmmaker or writer, but with a magazine, I could create a space that brought all of these disciplines together. It became a kind of total artwork for me, a medium where I could experiment freely. And that experimentation still drives me –maybe even more now than when we began.

OZ: Yes, restlessness is essential. You

have to stay uncomfortable. Comfort

is the enemy of creation. That doesn’t mean chaos – it means tension. A desire to question, to push, to remain awake. A good magazine is a form of insomnia. You can’t sleep through it.

OZ: Yes, exactly. It’s a wake-up call.

Culture shouldn’t put you to sleep. That’s the problem with so much media today – it’s about sedation. Distraction. I want Purple to disturb, to inspire, to seduce, but never to numb. Beauty isn’t perfection. It’s something that touches you, that carries a kind of truth. Sometimes it’s elegance, sometimes it’s rawness. But it always makes you stop and feel.

OZ: That tension is important to me.

From the beginning, we were never interested in creating something polished or purely aspirational.

We wanted to reflect life, culture, and art as they happen – imperfect, spontaneous sometimes contradictory. It was always about mixing theory and

practice. High ideas with everyday life. It might sound abstract, but it has to do with honesty. And that kind of honesty can survive the commercial aspects if you treat your advertisers and collaborators with the same sense of dialogue. Commerce is not the enemy – it just needs boundaries.

OZ: Definitely.

Especially with the rise of influencer culture and algorithmic thinking. There’s pressure to conform, to optimize. But I believe in the long game. In building something with depth. That’s why I still print. A printed page doesn’t disappear when you scroll past it. It stays. It insists on being seen. It’s a kind of resistance –against disappearance, against forgetting.

OZ: Yes, and memory is part of identity. You can’t build cultural memory through disappearing stories or trending topics. You need continuity. You need archives. That’s why a magazine is not just a product.

It’s a document. A trace. A witness.

OZ: It is. Japan’s post-war decision to

renounce war, to literally put peace into their constitution, is extraordinary. Especially when you look at the world today, where conflict and aggression are normalized, even celebrated. For me, that became a starting point to explore the deeper layers of Japanese culture. The art, the food, the fashion – all of it somehow

comes from that foundational principle of restraint, of reflection. It’s a culture of sensitivity. Of poetics. And it’s something we need to be reminded of in the West.

OZ: Exactly. I’m not interested in cultural tourism. We don’t need another travel guide to Tokyo. What

I wanted was a mirror. A way to

understand ourselves – in Berlin,

in Paris, wherever – through Japan.

What does their quiet say about our noise? What does their elegance say about our speed? That kind of reflection is essential in today’s world. Japan allows you to slow down your gaze. It’s a gift.

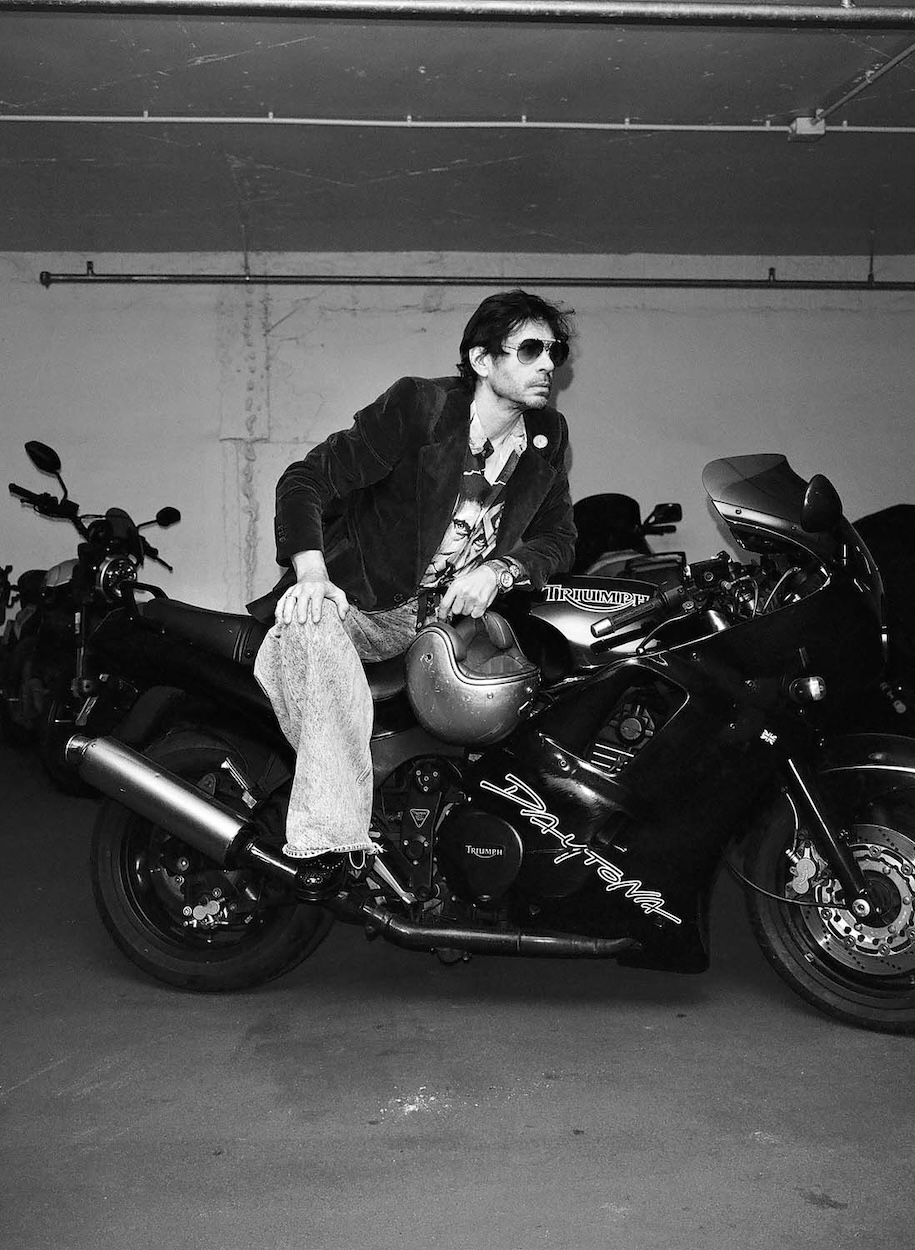

OZ: It is. There’s a return happening.

Young people are buying vinyl again. Film cameras. Printed books. There’s a suspicion toward digital life, and rightly so. So I want to make an issue that says: Here is why analog still matters. It’s not nostalgia. It’s a defense of presence. Of texture. Of slowness. All the things that make us human. There is an intimacy to analog.

You can’t fake it.

BEAUTY ISN’T PERFECTION. IT’S SOMETHING THAT TOUCHES YOU, THAT CARRIES A KIND OF TRUTH. SOMETIMES IT’S ELEGANCE, SOMETIMES IT’S RAWNESS. BUT IT ALWAYS MAKES YOU STOP AND FEEL.

OZ: It came from La Carte du Tendre, this poetic map from the 17th century that charted love as a landscape. I thought, why not reimagine that today? Could we map our sexuality – not as something functional or digital, but as

an emotional, poetic territory? A terrain of desire, indifference, mystery. It’s an artistic idea, but also a political one. In an era where sex is commodified, surveilled, and reduced to data, a map like this could reclaim its depth, its freedom. We are more than our profiles. We are more than our swipes.

OZ: Yes, exactly. A map. A real object.

Something you unfold, touch, get lost in. Like we used to with road maps. Today, we follow a screen. We don’t look at the landscape anymore. Taxi drivers don’t know their cities. Lovers don’t know their bodies. We need to reclaim space. Real space. The map is also a metaphor for attention. For care.

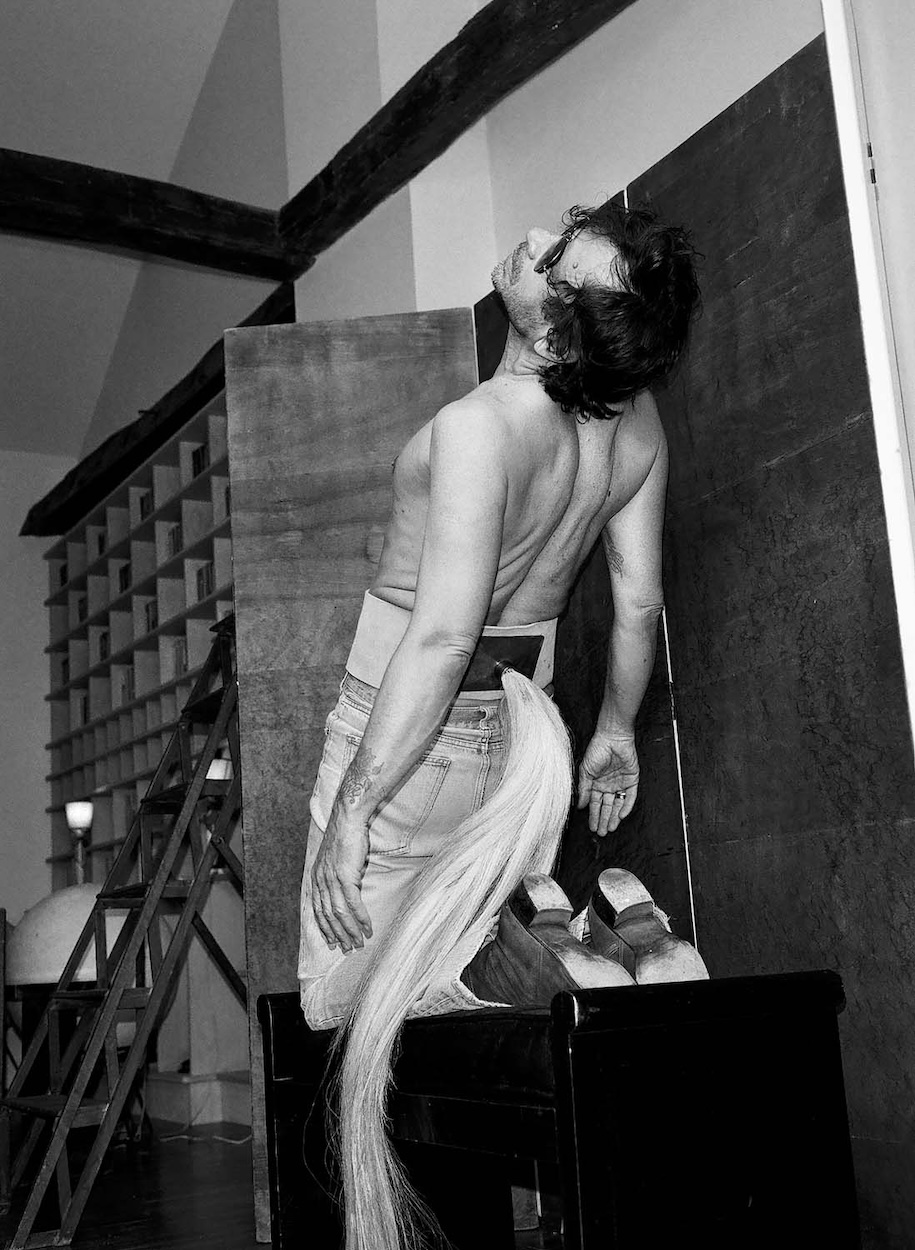

OZ: Absolutely. Creativity, desire, even

politics – they all begin with the body. And we are losing that. We’re being reduced to avatars, screens, profiles. It’s a disembodiment. That’s why analog is radical. It’s sensual. It’s real. It insists on human presence.

OZ: Very. I don’t do the layouts myself,

but I work closely with my designer,

Gianni. He’s a true artist. The layout, the typography, the rhythm of the pages – that’s where the magic is. It’s not decoration. It’s storytelling. Some magazines look nice but feel empty. I want Purple to feel alive. Every page is part of the narrative. It’s like composing a score. The silence matters as much as the sound.

OZ: Yes, if you count everyone – writers, photographers, stylists, assistants, printers. It’s a village. But even with all these voices, the magazine needs a vision. It needs a conductor. That’s my role. To orchestrate it without controlling it.

To let it breathe, but keep it honest. To say no when needed. To protect the magazine’s soul.

OZ: Yes, I’m 60 now. I still love what I

do, and I want to keep doing it. But I also know I won’t be here forever. So I think about transmission. How do I pass on the spirit of Purple? Not just the brand, but the method, the attitude. That’s the challenge. I want Purple to outlive me. So I hope someone will pick it up and continue, not by imitation, but by transformation.

OZ: I know, and that’s the paradox. I had to become visible – especially with social media. If I didn’t put my face out there, people wouldn’t understand what Purple was. But now it’s a bit of a trap. I don’t want to be the brand. I want the magazine to be the message. I want to disappear into the pages.

OZ: More than ever. Because print forces you to be intentional. Every page costs something. Every image has weight. There’s no infinite scroll. No algorithm. Just presence. I think people are hungry for that again. For something they can trust. A magazine is a commitment – not just of money, but of time, of attention. That’s sacred.

OZ: Exactly. That’s the real mission. To

awaken. To provoke. To inspire. And maybe even to create a little beauty along the way. That’s enough for me.

THERE IS AN INTIMACY TO ANALOG. YOU CAN’T FAKE IT.

YOU HAVE TO STAY UNCOMFORTABLE. COMFORT IS THE ENEMY OF CREATION.

TO WATCH: “MARTY SUPREME BY JOSH SAFDIE

"I have a purpose. And if you think that's some sort of blessing, it's not. It means I…

TO WATCH: “SOULEYMAN’S STORY” BY BORIS LOJKINE

A man trapped in a system that only values humanity when it can be used

TO WATCH: “NO OTHER CHOICE” BY PARK CHAN-WOOK

No Other Choice is not about losing a job, but about losing the self in a system that…

“I’VE MISSED OUR CONVERSATIONS” AT SCHLACHTER 151

I’ve Missed Our Conversations examines how artificial intelligence is reshaping emotion…

TO WATCH: “IMPATIENCE OF THE HEART” BY LAURO CRESS

The more Isaac tries to help, the clearer it becomes how thin the line is between care,…

TO WATCH: “A WORLD GONE MAD. THE WAR DIARIES OF ASTRID LINDGREN.” BY WILFRIED HAUKE

"If happiness is to last, it must come from within, not from someone else."