FOTOGRAFISKA X LUCAS MEYER-LECLERE

FOTOGRAFISKA X LML Adina Bier, the curator and innovative force behind the museum…

Photography by Sascha Rebrikov Interview by Louise Garier

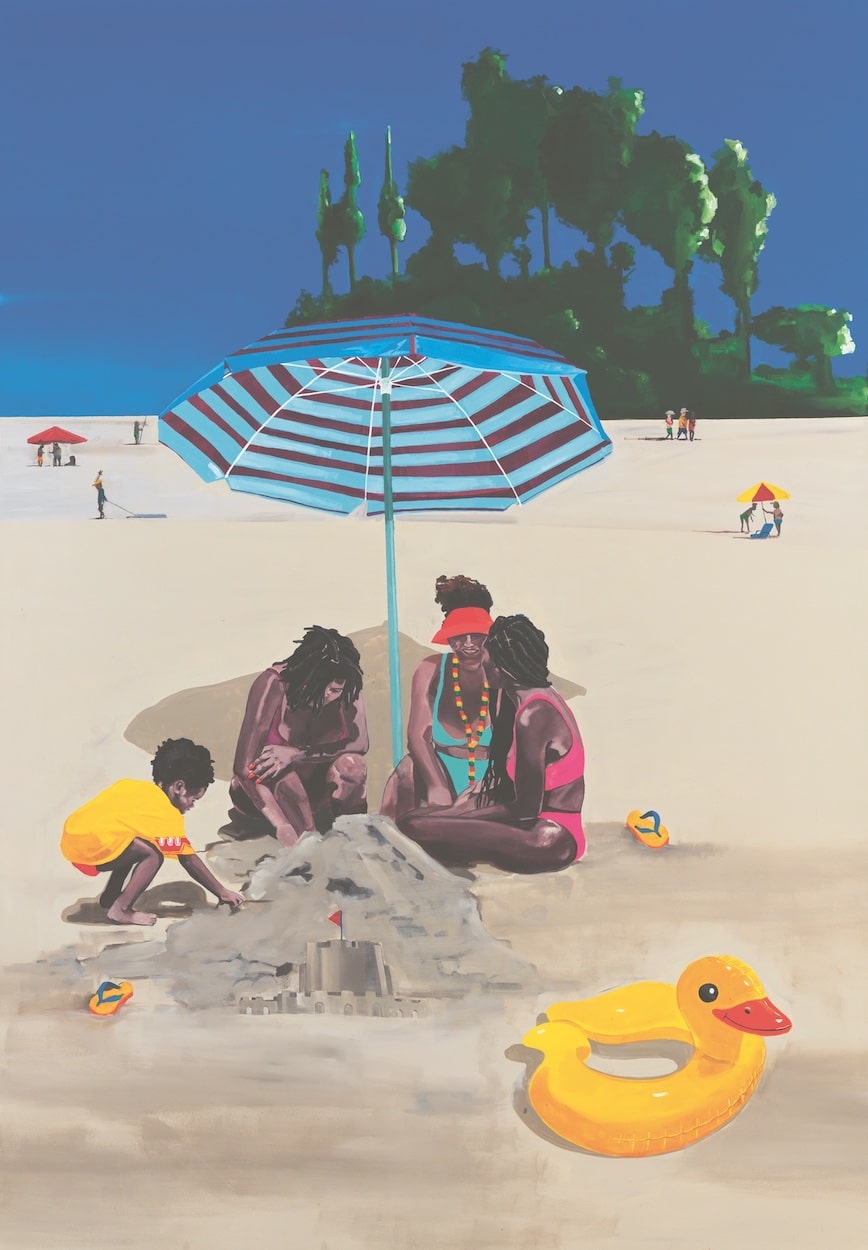

“The paintings reflect the logic that living a moment of love, affection or leisure is a political act.”

Numéro Berlin speaks to the multidisciplinary Brazilian artist taking on issues of identity and politics.

Brazil has a unique experience with racism. Although not often represented in ads and media, Black people are not a minority in the country, with mixed- and Black-identifying people making up more than 50% of the population. There are more than 100 million Black people living in Brazil — the largest Black population outside of Africa and roughly double that of the United States. Because of these demographics, many in Brazil — including its right-wing president Jair Bolsonaro — argue that racism isn’t really an issue for the country. Nevertheless, similar to other countries with a history of slavery, the Brazilian Black community faces disproportionate struggles when it comes to murders, police violence and exclusion from social mobility. São Paulo-born artist No Martins is a sculptor, painter and performance artist exploring these experiences and struggles of Brazil’s Black community as a central focus of his work.

The artist’s name, No Martins, is a pseudonym adopted during his teenage years when he started doing graffiti and pixação on the streets of São Paulo. Similar to graffiti, pixação is a specific Brazilian style of tagging buildings with thin letters that originated as a response to political billboards of the 1940s and 50s. According to the artist, the name is a rejection of the various oppressions imposed on the population by the State, followed by his maternal surname, Martins.

“My mother was part of a political movement fighting for housing and as a child, I would accompany her to meetings,” Martins says in an email interview. “Since I was young, I hung out with boys older than me and attended cultural and political movements close to my neighborhood. This helped to form my ethical and political conscience, as well as arouse my interest in trying to understand and discuss the structures of the society I live in and am a part of.”

A feature of Martin’s work, which includes painting, sculpture, performance and tapestry, are the bright colors and scenery that instantly place his work in his home. These places are filled with Black characters at the center of his narratives. Some of his pieces use symbolism to convey a message, like in his sculpture “Rules of the Game” (2021), which consists of a custom chess board with mostly black pieces on the outside and only white pieces on the inside. Other works, like his ongoing “Political Encounters” series, — which is currently on display at the Museu de Arte Moderna de São Paulo — use common everyday scenarios as a jumping off point for deeper discussions.

“In this series, I discuss how important coexistence with our peers is,” Martins says. “I portray meetings that seem futile and banal and elevate them to a much more important level; these everyday scenes become moments of transforming discussions, exchanges, teachings and learning. The paintings reflect the logic that living a moment of love, affection or leisure is a political act.”

Still, a large part of Martin’s work centers around police violence and over-incarceration in Brazil, which has the third largest prison population in the world. This year marks the 30th anniversary of one of the country’s largest massacres, Massacre do Carandiru, where police came into the Carandiru detention center and brutally killed 111 inmates following a prison riot. Although 74 police officers were originally tried and sentenced for their roles in the massacre, a Brazilian court decision in 2016 declared the trials null. Many of the problems, such as overcrowding and poor living conditions, are ongoing in the Brazilian prison system. Martins is currently working on a series of installations, objects and paintings related to the massacre.

“A large part of my work analyzes daily life in Brazil, especially for Black people, their interpersonal relationships and the problems they face, issues that are consequences of racism and the colonial formation of Brazil, which to this day unfold in the lack of the most basic rights, such as access to health, education and justice,” Martins says.

While Black equality leaders and movements have influenced Brazilian Black communities, the nuances of Brazil’s history with slavery and use of money and class to segregate society rather than legal codes, make many areas of the fight distinct from the Black Lives Matter Movement. Although the streets of Brazil saw demonstrators after the death of George Floyd, the killing of 14-year-old João Pedro in Rio De Janeiro sparked its own protests with slogans like #jábasta, meaning enough is enough.

“There are many differences between the fights for racial equality in Brazil and the United States,” Martins says. “One of the main distinctions is that Brazil was the last country to abolish slavery and the place where the largest number of enslaved Africans in the world were trafficked. Brazil is still crawling towards some achievements, even being the largest black population outside the African continent. But like Black Lives Matter, Black movements in Brazil have great importance, potency and transformational power for the whole world.”

For Martins, Brazilian culture is key to addressing the problems of his country.

“I believe that the unique identity that I have been consolidating in my work is a mirror of this culture,” he says.

FOTOGRAFISKA X LML Adina Bier, the curator and innovative force behind the museum…

Photography by Sascha Rebrikov Interview by Louise Garier

Electronic beats Prague, As part of its extended "Summer of Youth" campaign, German…

Words by Marcus Boxler

IN CONVERSATION WITH RAFA SILVARES, Brazilian born and Berlin-based artist Rafa…