IN CONVERSATION WITH SOPHIE THATCHER

Sophie Thatcher, best known for her role in the critically acclaimed series…

Photography by Jason Renaud; Interview by Louise Garier

This year, Berlin experienced a special kind of fusion: Club culture merging with denim couture.

With this in mind, Sven Marquardt opened a unique exhibition with G-Star Raw entitled “11-1”.

Sven gave Numéro Berlin an insight into the thoughts behind the exhibition and special campaign.

“The camera became a means of expressing our collective and my personal sensibilities.”

That was such a long time ago—four decades by now. It was in the early 1980s. I underwent training as a photographer, which was a dual education at the time, including working as a camera assistant for East German television. After that, I mostly had odd jobs at the theater. I wanted a profession that would give me a certain degree of freedom, as I didn’t enjoy it much after completing my apprenticeship. So, in the early 1980s, I began immersing myself in the subculture of Prenzlauer Berg, using my camera to capture portraits of people in my surroundings whom I found intriguing. These were individuals whose experiences resonated closely with my own. This gave rise to a zone, a community of creative young people. The camera became a means of expressing our collective and my personal sensibilities. I believe that this essence has endured over time. This sentiment is also somewhat embedded in the G-Star campaign, drawing from the club culture and the many years I’ve spent working in Berlin’s nightlife. And now, in recent years, my priorities have shifted more towards photography again.

I attended an art exhibition opening in Mitte last Friday, at the location where the King Size Bar used to be. In the backyard, there is now a new exhibition space, and that was actually the entrance. You had to walk through the backyard, and I couldn’t help but notice that nothing had been done to the buildings in that area for 30 years. It truly looked like a relic from a different time, much like how the entire Prenzlauer Berg used to be. There was a lot of vacant space, and people didn’t really want to live with coal stoves, although most did. We loved the apartments because they were incredibly spacious and had old wooden floors and doors. Dealing with the coal stoves could be a bit cumbersome, but you could live in these huge apartments for very little money. It was kind of cool in a way. It was during a time of dictatorship and extreme confinement, but there were these niches if you could discover them. For instance, if an apartment had been vacant for more than three months, you could claim it. Or you could move in by reporting the vacancy, and you’d get the lease because they were just glad to have someone in there. So, in a way, we all lived in these grand estates hidden away in the courtyards. I think it was quite a small circle; there were no clubs, just a few concert venues. But even those were often influenced or controlled by the Stasi and the state. So, you had to set things up illegally sometimes. That was Prenzlauer Berg back then—raw and very honest. A bit of the opposite of what it is today.

“I didn’t want to sell my photography for peanuts, like taking photos of shopping carts, but rather to make enough to pay my rent.”

Of course a huge happening: the fall of the Berlin Wall. Berlin Mitte was somewhat like a no-man’s land back then. The entire area around the old Neue Schönhauser Straße was quite vibrant, with occupied buildings and temporary clubs that sprang up. I found this to be a profound transformation for the city, particularly in Mitte. In the 1980s, I lived in a punk and new wave scene, surrounded by various artists. This marked the birth of club culture in this no-man’s land, in places that used to be on the former border strip, such as Tresor and E-Werk. It became a new hub for me—autonomous, a bit chaotic, and somewhat underground. This was something entirely new for a reunited city, as club culture only really emerged in the early ’90s. I started working in that scene at the time and actually took a break from photography for a few years. Perhaps I was searching for my own identity, and photography didn’t play a significant role during that period. I even thought it might have been more of an “Eastern” thing. However, my passion for photography resurfaced in the late ’90s. I’ve been taking photos for so long now, and in recent years, it has been an incredibly intense period for my photography. It’s almost three times the duration of the East German time, but it has certainly left a lasting impact on me. That is correct. There are two things that are quite interesting about it. One is the journey into working with the beginnings of club culture. It’s a way of finding oneself again.

I didn’t want to sell my photography for peanuts, like taking photos of shopping carts, but rather to make enough to pay my rent. The cost of living had gone up, and it was no longer sustainable with just a few marks a week. So, I thought, why not find a job where I’m already spending my time partying and connect the two in some way.

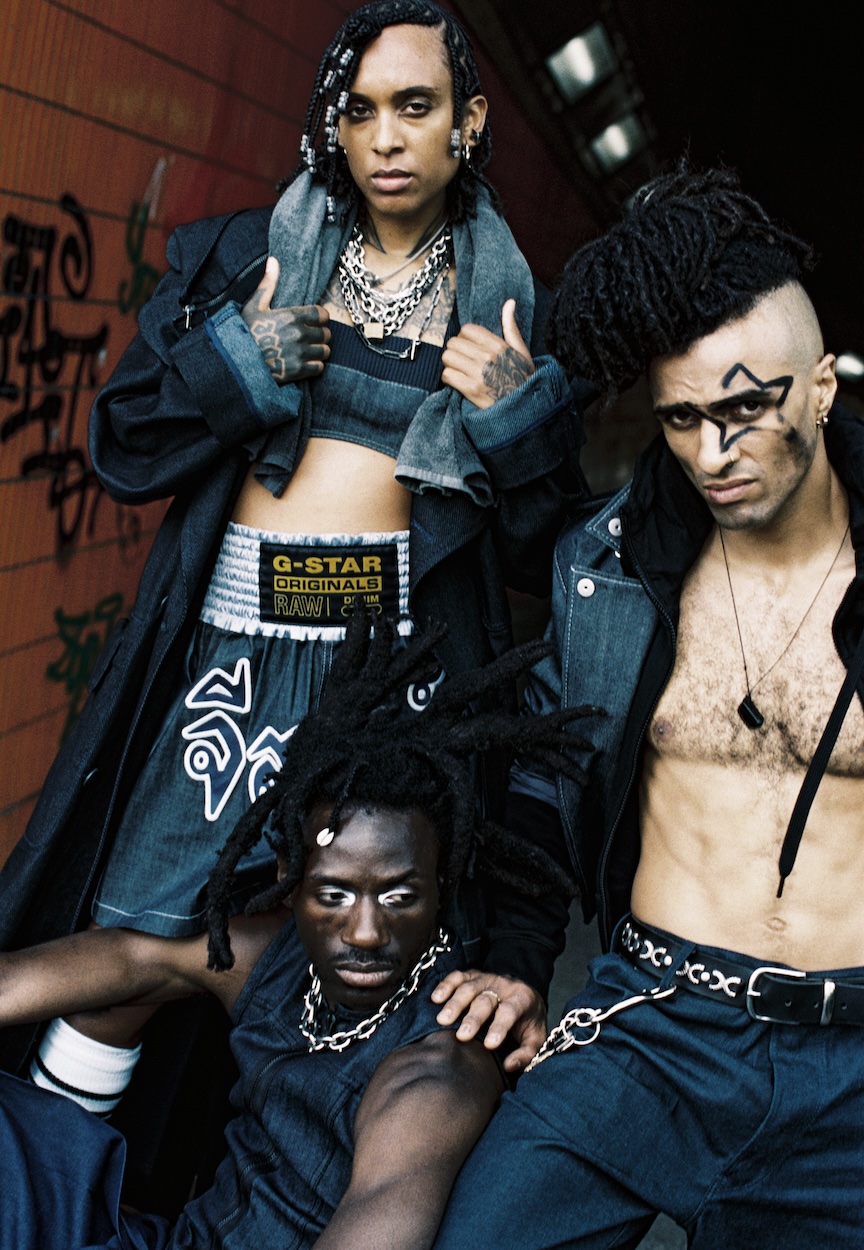

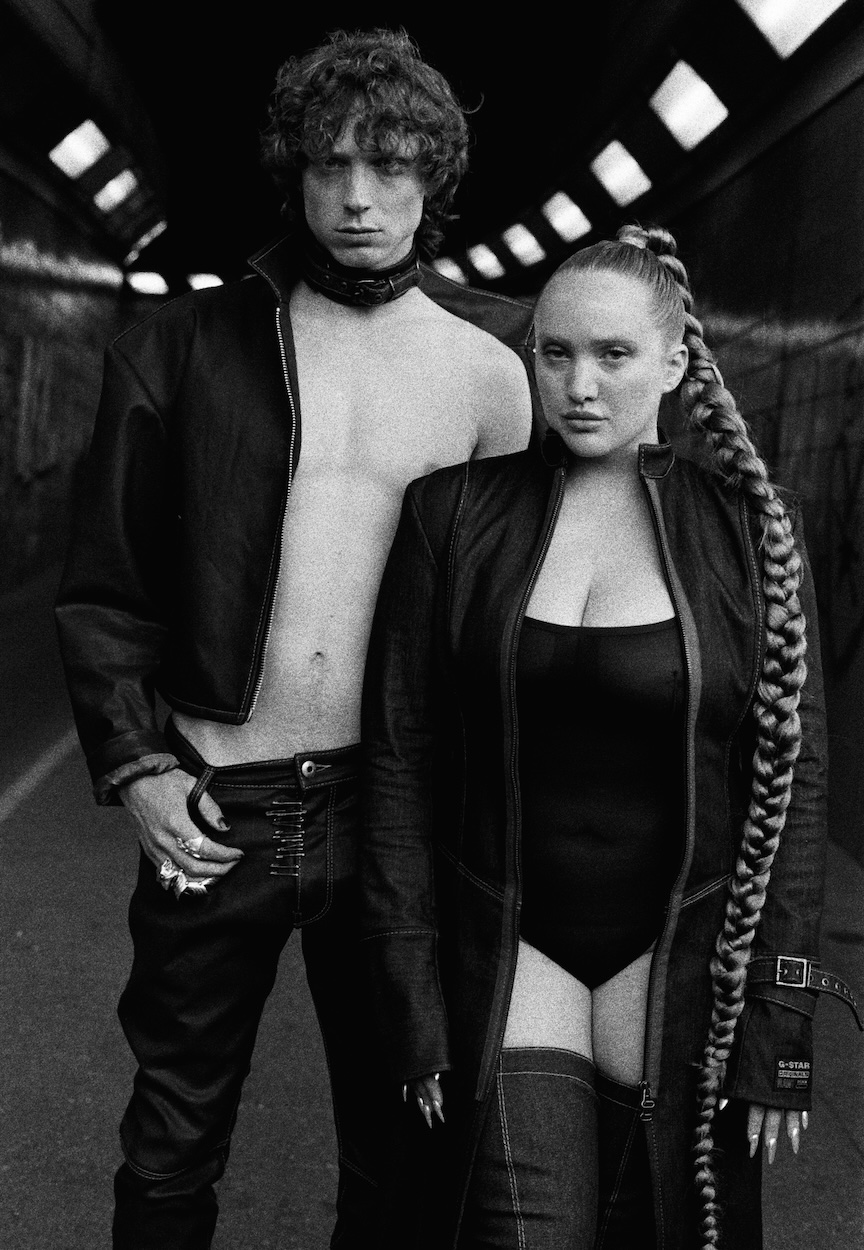

“The entire campaign was conceived within the context of the club scene, a sort of homage to a much younger generation.”

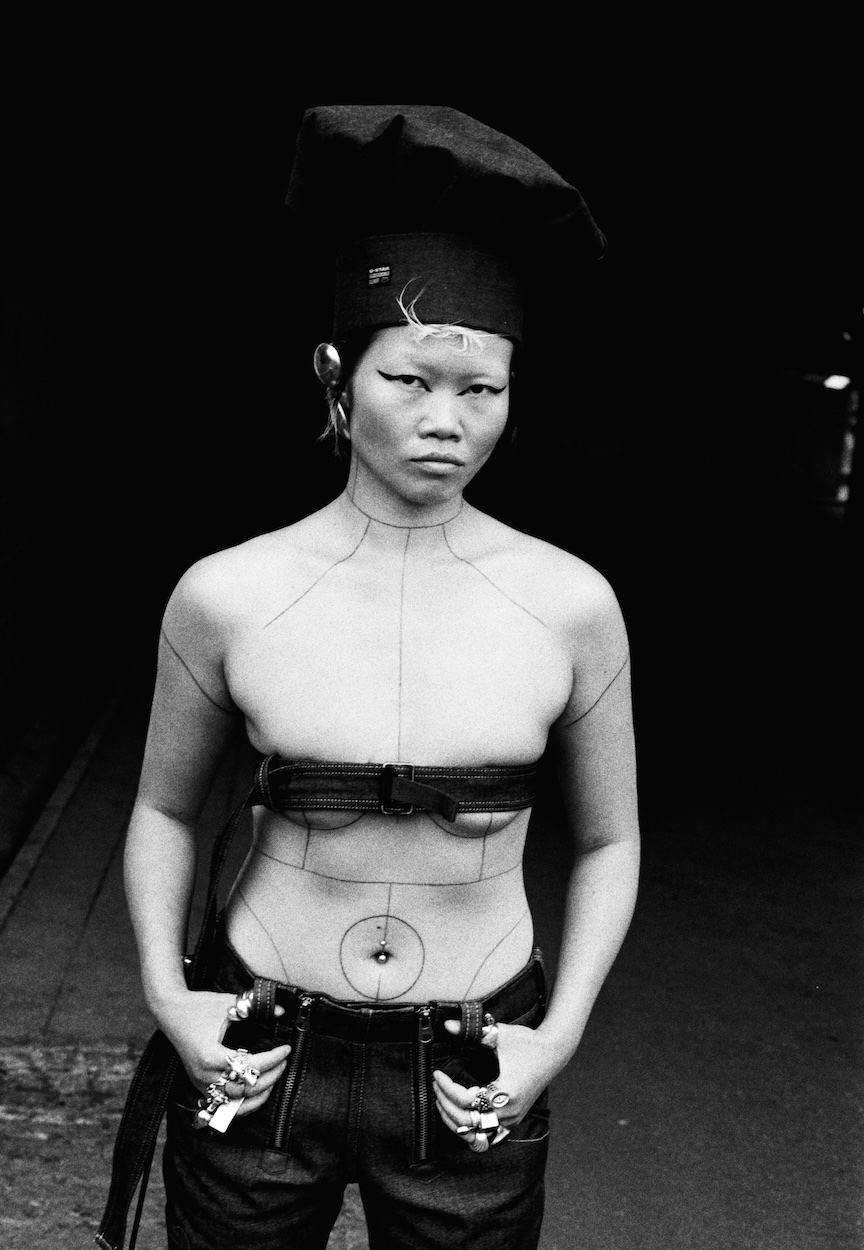

I don’t think I can put a specific label on it, but there was something about the style, appearance, and overall atmosphere in my surroundings that felt somehow similar to my own. I have an appreciation for contrasts and disruptions. I also find the allure of model-like beauty quite intriguing and interesting. However, I also find it quite satisfying when you can deconstruct and reassemble these opposites within the realm of styling.

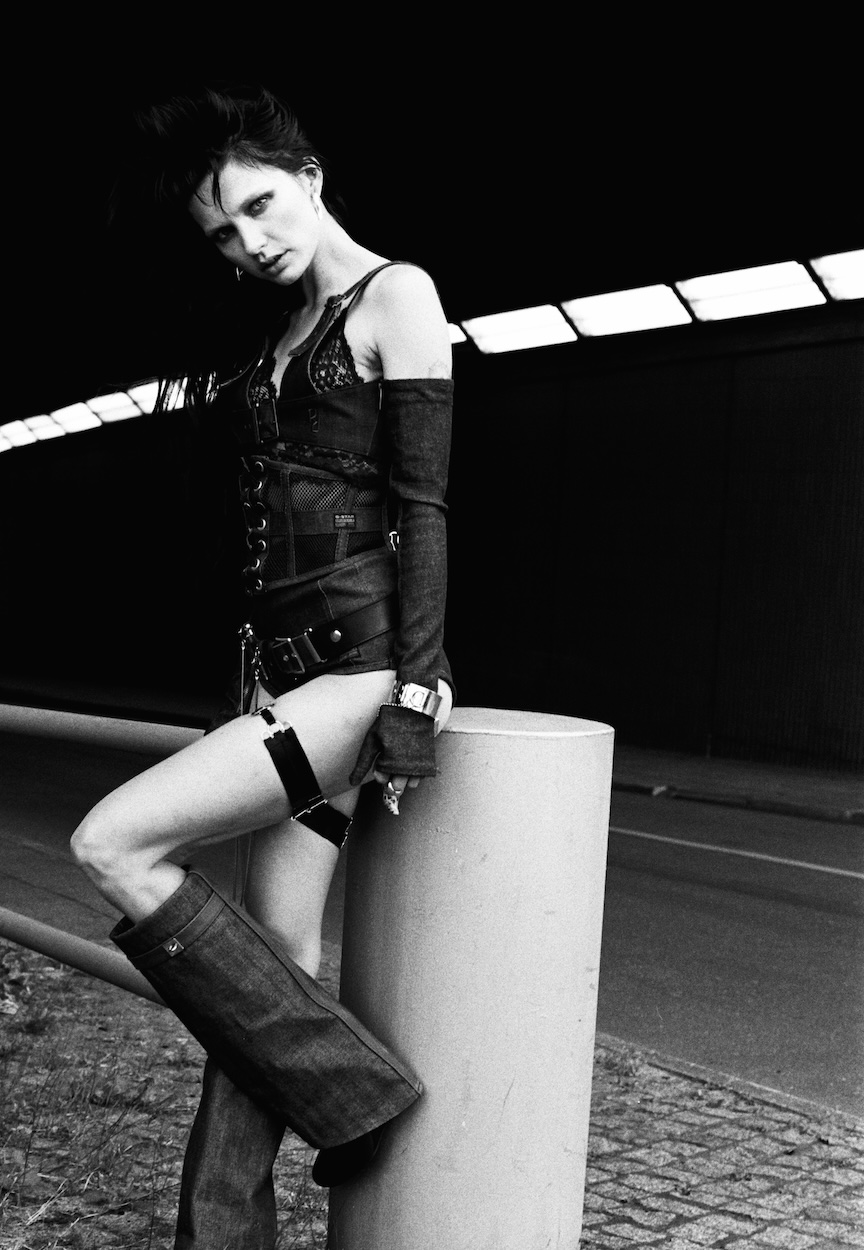

Well, Hella Schneider for example has a fantastic personal style. That, of course, was a bit of the approach in the G-Star campaign. They had the idea to draw inspiration from the private looks of the models, the outfits they wore when they went out partying, and then recreate those looks. I found this to be an intriguing concept, as it gave off a sense of jeans couture. So, the models came to the casting in their favorite outfits, which were then measured, documented with a few Polaroids, and off they went. For example, Hella was given a skin-tight coat and over-the-knee boots that required three people to help her put on. This highlighted and showcased her femininity beautifully. Everyone is unique in their own way, after all. The entire campaign was conceived within the context of the club scene, a sort of homage to a much younger generation. I work at the door myself, and I think it’s great to see and hear what defines and impacts the new generation, how they go out, and how they perceive me. It’s a source of inspiration because it’s a generation with which I wouldn’t typically have much in common.

Especially with G-Star Denim, it’s associated with that dark, clear, and almost purist material. G- Star Denim, in my mind, isn’t like some other brands that often look overly embellished, or their items are deliberately designed to sell well. Denim, for me, is a timeless classic that continually reinterprets the spirit of the times. What inspired me about G-Star is that most of the models came wearing an old pair of jeans. These were then reimagined and given a new life. They gifted me a pair of pants that’s quite baggy and looks incredibly cool. It’s a bit heavy and has a tough texture, but it still looks cool. And there are other pieces like that too. Somehow, each piece carries its own memories.

“It seemed like fashion and art had intertwined and merged a bit, which I believe is a beautiful narrative.”

I’m often associated with black and white photography, but I also enjoy working with color photography. I work in analog. I always tell my clients that it will be 2/3 black and white and 1/3 color. For the campaign, there was a great mix of both, and I believe that it doesn’t create a contradiction but rather maintains a unified look.

Perhaps black and white is more melancholic and dramatic? I learned photography that way, perhaps influenced by the school of East German photography, which boasts remarkable photographers. Many of my role models from that time also primarily worked in black and white. But, in reality, I do both, black and white as well as color photography.

The Art Week went quite well with all the events that were happening. There was a high level of interest, and you could have attended three fantastic events every day. It was bustling with activity, and there were so many exciting things going on. I believe Fotografiska also opened during that week. I found the entire week to be very eventful and significant for the city. It seemed like fashion and art had intertwined and merged a bit, which I believe is a beautiful narrative. Large brands supporting artists – that’s a great story.

“Berlin is still very attractive to the outside world, and I believe we should make the most of it, however that may be done.”

I think it’s all about club culture and the people themselves. We photographed at the ICC, in the back, where there are bicycle lanes and strange tunnels in that still-vacant property. Even though the building itself isn’t prominently visible in the campaign, it’s always about that tunnel situation with the tiles. It could have been an entrance or exit, but it’s the atmosphere that the building exudes. That’s why I find the locations where we shoot the pictures to be quite important. Even if it ends up being a close-up shot, there’s something about the overall atmosphere that I believe influences it. I used to drive there beforehand, checked the lighting situation, and hoped for good weather. The inspiration for it all was the city, the people with their stories, and the city itself in combination with the production.

You can’t force something like that by creating a location. It requires interest and investors. We saw that with the Fashion Week and its excursion to Frankfurt. I understood that as well. These are things where I think it doesn’t benefit the city because something like this needs to grow and emerge, and sometimes it might take a few years, but you have to maintain your vision. Of course, money always plays a role in this. Berlin is still very attractive to the outside world, and I believe we should make the most of it, however that may be done. But, as we’ve discussed, the Art Week was actually an excellent example of what happens when art and fashion merge. However, the Fashion Week still seems a bit rough around the edges.

We have some highlights that are really cool. I always enjoy events like these. It’s a concentrated burst of attention, and when you see glimpses on the internet and think, “Wow, what elegance,” or witness a fantastic new trend. I always look forward to events.

Yes. It would be terrible if we didn’t have it. I mean, Berlin is a big city. We have such a massive tourism scene. I also believe that consuming the brand, on which brands depend, comes from people both within and outside the city. Some may visit the city and enhance their stay by buying a couple of new items from someone who represents this city.

Sophie Thatcher, best known for her role in the critically acclaimed series…

Photography by Jason Renaud; Interview by Louise Garier

"We have to create something that has a purpose and is useful. And not forced by the…

Interview Carolin Desiree Becker

Supporting Sydney’s cultural scene: This month’s collaboration reminds us of happy…

Interview by Sina Braetz