Interview with Charlie Stein, on painting as a radically contemporary medium at Kunsthalle II, Mallorca

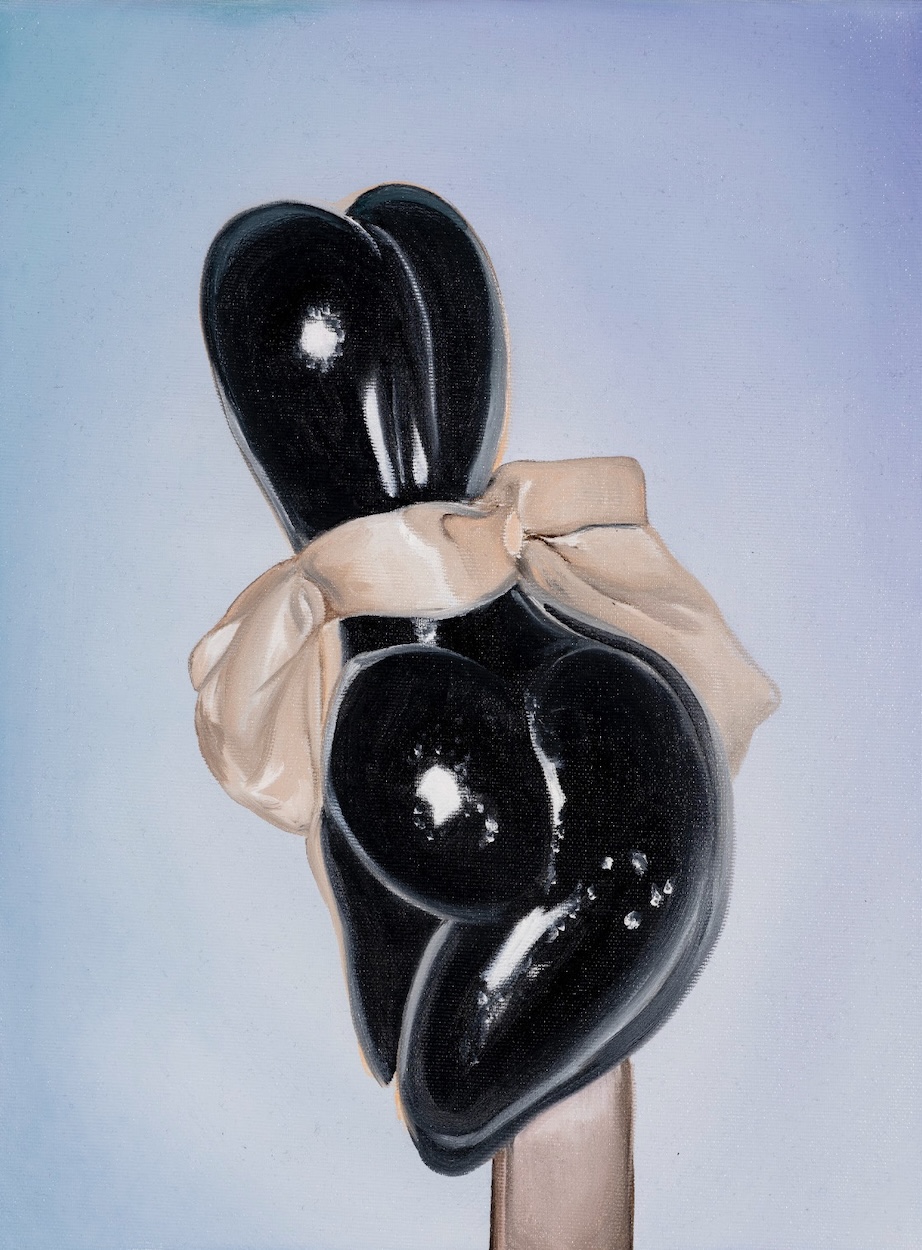

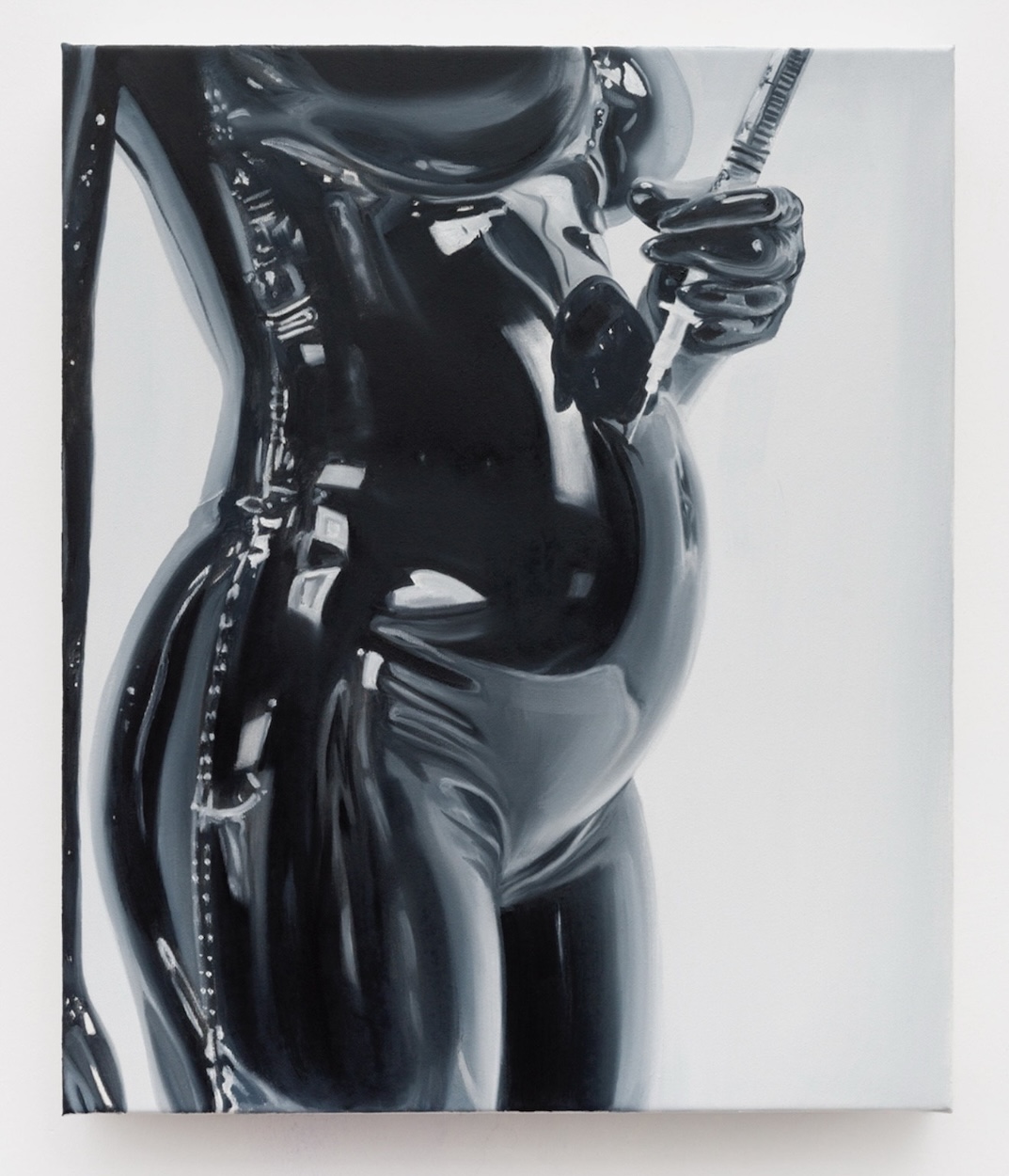

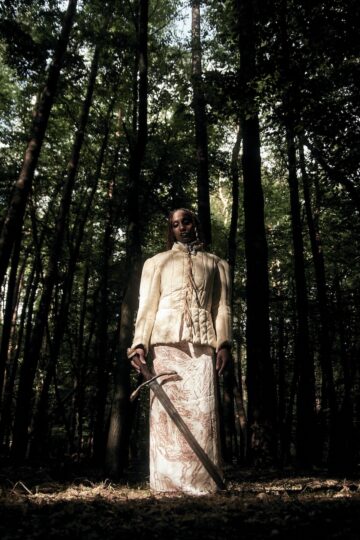

Berlin-based artist Charlie Stein explores the shifting boundaries where intimacy meets mediation and human presence becomes entangled with artifice. Her paintings depict padded, latexed, or otherwise encased figures that serve as metaphors for how desire, vulnerability, and memory are filtered in a digitized world. What first appears familiar, such as an embrace or a protective gesture, is destabilized through subtle distortion: forms become ambiguous, readability is interrupted, and the line between figure and object collapses. The works stage encounters that feel at once tender and estranged, protective and unsettling—reflecting how contemporary intimacy is continuously negotiated through layers of insulation, screen, and code.

Motifs like puffer jackets and synthetic skins heighten this paradox, suggesting both insulation and exposure, intimacy and alienation. These visual strategies mirror how screens and avatars shape our connections today, making the paintings’ surrealism feel fitting for contemporary experience. Despite the artificial qualities of her subjects, Stein emphasizes the persistence of longing, tactility, and memory—qualities that resist the flattening effects of digital culture. Her practice positions painting as a counter-archive, a medium that preserves sensations too fleeting for technological life and a space where the affective weight of presence endures, even when refracted through layers of simulation.

This autumn, Stein will introduce new paintings in two major solo exhibitions in Mallorca: The Real Thing at Centro Cultural Misericordia, Palma, and Everything Not Saved Will Be Lost at Kunsthalle CCA Andratx.

Having previously met Charlie in her ISCP studio in New York and her studio loft in Berlin, this time the conversation took place in the non-physical space of the internet — in the very space her paintings love to haunt.

Charlie Stein: I like the friction between the two titles. The Real Thing is taken from an obscure Australian pop song. Everything Not Saved Will Be Lost is a corrupted Nintendo meme but functions as a reminder that nothing is permanent. I want audiences to sense both at once: the desire for authenticity and the awareness that it can slip away at any moment.

Both titles trace back to corporate language. The Real Thing first struck me in Australia through Russell Morris’s cult psychedelic track, written during the Vietnam War as a sly riff on Coca-Cola’s famous slogan. The song folds protest and romance into one, weaving in even jarring WWII samples, which makes it political, magical, enigmatic, and subversively romantic all at once.

Everything Not Saved Will Be Lost originated in ’90s pop culture, as a variation of the Nintendo quit screen. The original “Anything not saved…” was remixed through Reddit and meme culture into the more poetic, aphoristic phrase “Everything not saved will be lost”. I asked myself why this incorrect version became more widely shared than the original quit-screen message, and I think it’s because we feel a desperate need to find meaning in an increasingly technologized world. We want deeper meaning in the magical devices that surround and haunt us; otherwise, we have to accept that we are just nodes in a ginormous internet brain that spans the planet which we feed into—and which feeds off us.

CS: The imagery of puffer jackets in Virtually Yours grew out of a deeply personal experience: visiting my partner on what would become his death bed in the ICU, where every attempt at contact was mediated through protective layers of latex gloves and glossy clothing. Those barriers made touch at once tender and distant, and I began to see the padded surface as a kind of interface — protective yet suffocating, intimate yet estranging.

I don’t see Virtually Yours — or the “puffer jacket series,” as you called it — as only about personal experience, though this is present in the work. I began the series a year or two after my partner’s passing, and over time I’ve come to see that it resonates with many kinds of relationships I navigate — personal, professional, and even metaphysical.

CS: They do a couple of things I really appreciate. The figures are all Trojan horses: an actual person is never shown. They remain mysterious, even to me, because they are portraits that deflect their own readability. They refuse to be easily decoded through gender, race, or class. That ambiguity allows me to work in an investigative mode.

At the same time, these figures connect to how we experience bodies through screens today. Time and again, I paint glossy black surfaces that evoke a smartphone display—smooth, light-emitting, touch-sensitive. When you touch your phone, nothing really physical happens: a tiny electrical signal registers, is translated, and becomes an action. On canvas, I turn that into an image of dissolution: touch without object, intimacy between skin and surface. We stroke our phones thousands of times a day—far more than we touch our loved ones, or even ourselves. That strange redistribution of tenderness fascinates me.

So the figures hover in this in-between space: half-human, half-object, intimate yet untouchable. They mirror contemporary identity as something mediated, constantly translated through layers—of fabric, of screen, of code. But they also insist on mystery, on resisting total capture. For me, that’s the paradox of being alive right now: we are more visible than ever, yet our true presence still flickers between surfaces.

CS: That’s a good observation. I would argue that painting is still one of the most successful storage media for images that we have. We know how to preserve oil on canvas for centuries. Every major museum employs teams of conservators who specialize in stabilizing pigments, repairing canvases, and slowing down the aging of oil paint. Compare that with the fragility of digital images: formats become obsolete, hardware breaks, and even when stored carefully, files can vanish because the infrastructure that supports them collapses. Rhizome and similar organizations are working on digital preservation, but the knowledge of how to keep a JPG alive for the next half-millennium is far less secure than the knowledge of how to preserve an altarpiece from the fifteenth century.

Painting to me is not nostalgic at all, it’s radically contemporary. As a medium, it guarantees visibility and longevity in a way digital storage still struggles to achieve. Think of VHS tapes: they’ve degraded, the players have disappeared, and whole archives are lost. By comparison, a painting, even when cracked or darkened, remains legible, restorable, and transmissible across generations. So when I paint, I’m not just making an image; I’m choosing a medium that resists disappearance.

CS: Living in different countries has made me acutely aware of how identity is not fixed but constantly dissolving and reforming. You carry fragments of language, gesture, and intimacy from one place to the next, shedding and accumulating layers like skins. This fluidity is mirrored in my paintings, where figures often appear padded or encased, melting or half-dissolved, suspended between categories.

When I lived in Beijing, I became hyper-aware of my own body as a marker of difference. During my daily bus rides and errands I didn’t experience myself as different until I caught my reflection in the window and saw an alien staring back. Blond hair, pale eyes, light skin. That estrangement came with its own contradictions. There was comfort in difference, but also the undeniable recognition of privilege: I could drift through that space with a kind of immunity, while others – the larger part of the world population – carried the daily weight of structural racism. Whiteness represents only a minority of the global population; it is neither a norm nor a standard for others to live by. Becoming aware of one’s own privilege—and the traces of racism within one’s own thinking—is a necessary beginning. To inhabit that contradiction can be unsettling, but it matters. I feel this body of work largely takes skin colour out of the equation and allows me to speak to more universal topics that may be relevant to anyone at some stage.

CS: I don’t try to separate the personal from the universal. My paintings often begin from lived experience, but I treat those moments as material that can shift and expand into broader conditions. In the Virtually Yours series, for example, the padded and encased figures carry traces of grief and intimacy, yet they also speak to how all of us navigate mediation, distance, and vulnerability today. I think the balance lies in letting the work remain open: it is never only about me, and never only about the universal, but always suspended in between.

CS: Yes and No. In Berlin the puffer jacket is what the baseball cap is in America: a uniform, not a fetish. Everyone wears those big black glossy coats through the endless winters. Straps, latex, vinyl belong to the city too, but what stayed with me was the sheen itself, that glossy black that always recalls the surface of the iPhone — cold, omnipresent, the portal through which so much of life now passes.

Even if those cultural markers do not always translate, I try to make work that unfolds on multiple levels. At first glance you might see figures embracing or fighting, then notice textures, contrasts, titles, the meaning I try to inscribe into each canvas. I want to make works I could live with for the rest of my life. Paintings that contain something I cannot fully grasp, that will mean something different to me ten or fifteen years from now. Like the box the pilot draws for the Little Prince, they withhold clarity so the imagination can keep moving.

The objects I depict are vessels. I try not to seal them shut, so that I can always ask: if this painting were real in another realm, what would I encounter if I skinned these forms? That question keeps me excited and a little anxious, as if I am afraid to discover what they truly hold.

CS: That is a difficult question, because what I see right now is a strong current of nostalgia in art, and that troubles me. By nostalgia I mean the insistence that art must look handmade in order to be authentic, as if visible brushstrokes or artisanal labor were guarantees of value. It is a romantic idea, but one that reproduces a very narrow model: the solitary genius in the studio, detached from questions of economy, infrastructure, or technological change. Historically, this model has been available only to those with security and privilege. For everyone else — women, minorities, artists without resources — it becomes exclusion disguised as purity.

My own practice pushes against that. I want painting to remain a valid contemporary medium, not because of its nostalgic aura, but because of its unique capacity to store and transmit sensations across time. At the same time, I engage with writing, installation, and digital media, because these forms expand the conversation and allow new ways of thinking about intimacy, mediation, and presence.

CS: I would say both. Technology alienates and connects at the same time. There are sparks of intimacy when you catch a friend mid-meme in a chat, or when FaceTime makes it possible for my mother and me to sustain a close relationship across distance. At the same time, so much of life is outsourced to us as end-users — travel apps, booking systems, endless contracts — that our hours are consumed by tasks disguised as efficiency.

Philosophically, though, I think technology is not just a tool we use, but part of what defines us as a species. Aside from our ability to cry tears, the drive to invent and advance technologies is the one thing that sets us apart from other animals. It is both our curse and our gift: the source of alienation, but also of entirely new forms of intimacy worth embracing.

Phillip Edward Spradley is an American writer, organizer, and producer, and the latest addition to Numero’s circle of contributors. He grew up wanting to be a dark wizard, but ditched the dream when he realized magic was officially dead.

Technically a bit internet-illiterate, Phillip is nonetheless obsessed with the collision of art, technology, and the messy brilliance of interdisciplinary collaboration. He’s organized a dozen exhibitions, produced thousands of cultural events, and has a soft spot for hardcore music and omakase dinners.

Phillip has worked his own programming magic for institutions such as Hauser & Wirth, the Smithsonian Institution, Yale University, and the National Arts Club, just to name a few.

For Numero, he caught up with artist Charlie Stein on the occasion of her recent exhibitions in Mallorca: The Real Thing at Centro Cultural Misericordia, Palma, and Everything Not Saved Will Be Lost at Kunsthalle CCA Andratx.

Credits

Interview by Phillip Edward Spradley

All Images courtesy of Charlie Stein

CAMPAIGN – Alliance of the Epic II

CAMPAIGN – Alliance of the Epic II

FIGHT ISSUE VOL. B – MURDER ON THE DANCE FLOOR

FIGHT ISSUE VOL. B – MURDER ON THE DANCE FLOOR

TO WATCH: HELGA PARIS – FOTOGRAFIN BY HELKE MISSELWITZ

"I always just wanted to photograph what I love."

A NON-EXHAUSTIVE APPRECIATION OF THE I’S THAT HAVE SHAPED MINE

“I WANT TO ACKNOWLEDGE SOME OF THE WRITERS …

BUFF MEDICAL RESORT: WHERE MEDICINE, INNOVATION AND LUXURY MEET

A New Vision of Health: On a mission to set new standards in preventive and regenerative…

In Conversation with Martin Mai

Numéro Berlin sat down with photographer and film maker Martin Mai to talk about his path…