IN CONVERSATION WITH SOPHIE THATCHER

Sophie Thatcher, best known for her role in the critically acclaimed series…

Photography by Jason Renaud; Interview by Louise Garier

When you enter the Belvedere in Vienna, you don’t expect a lower floor at all, which is so intimate and almost confining.

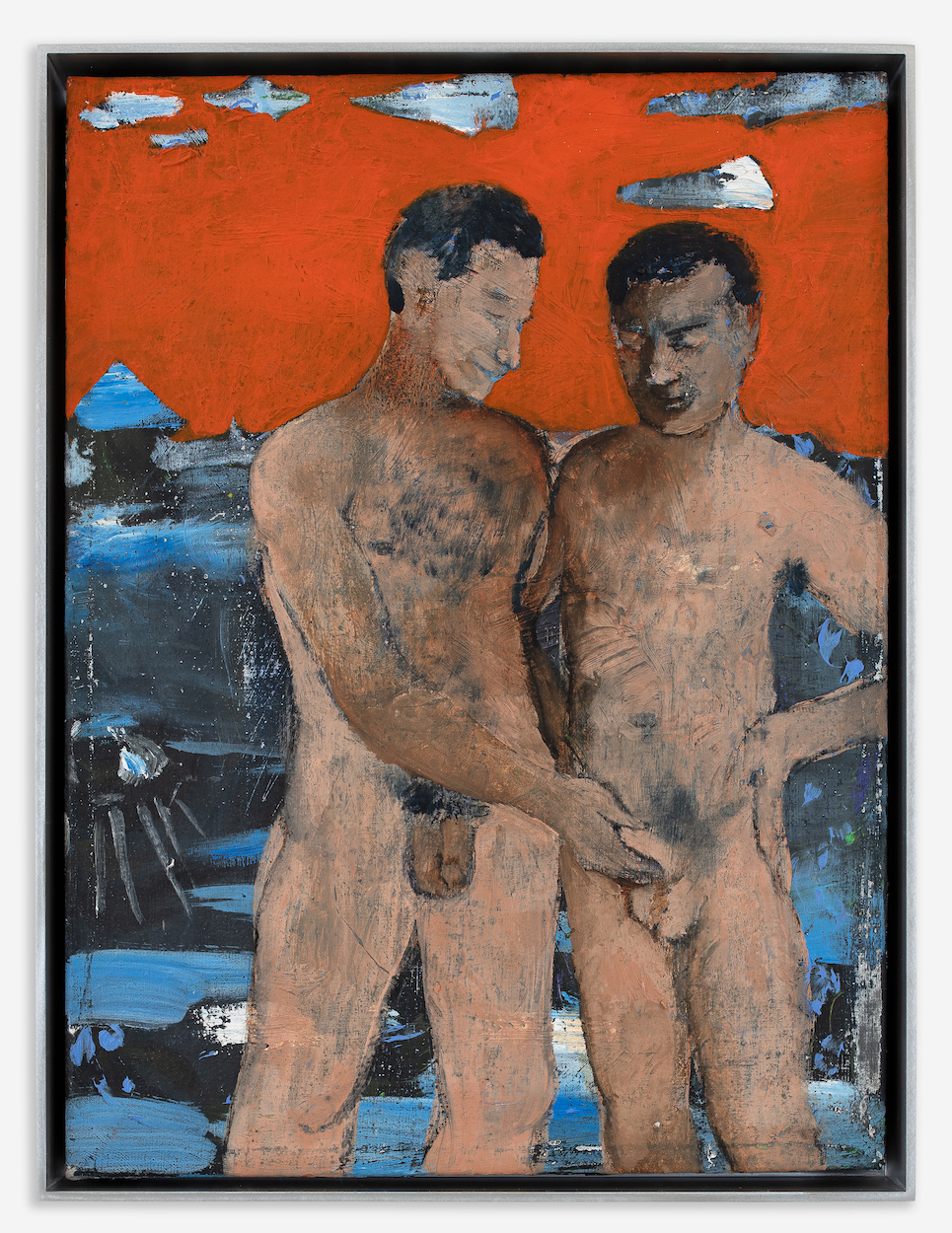

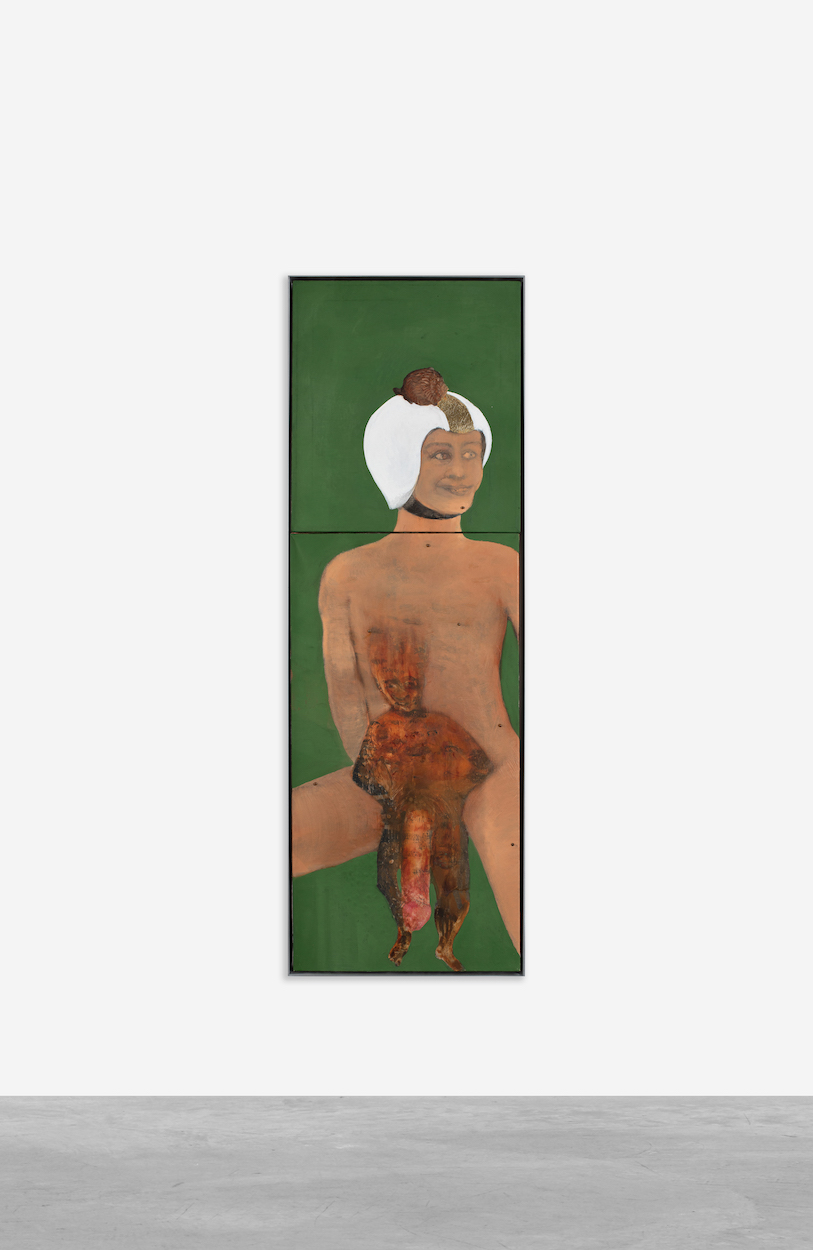

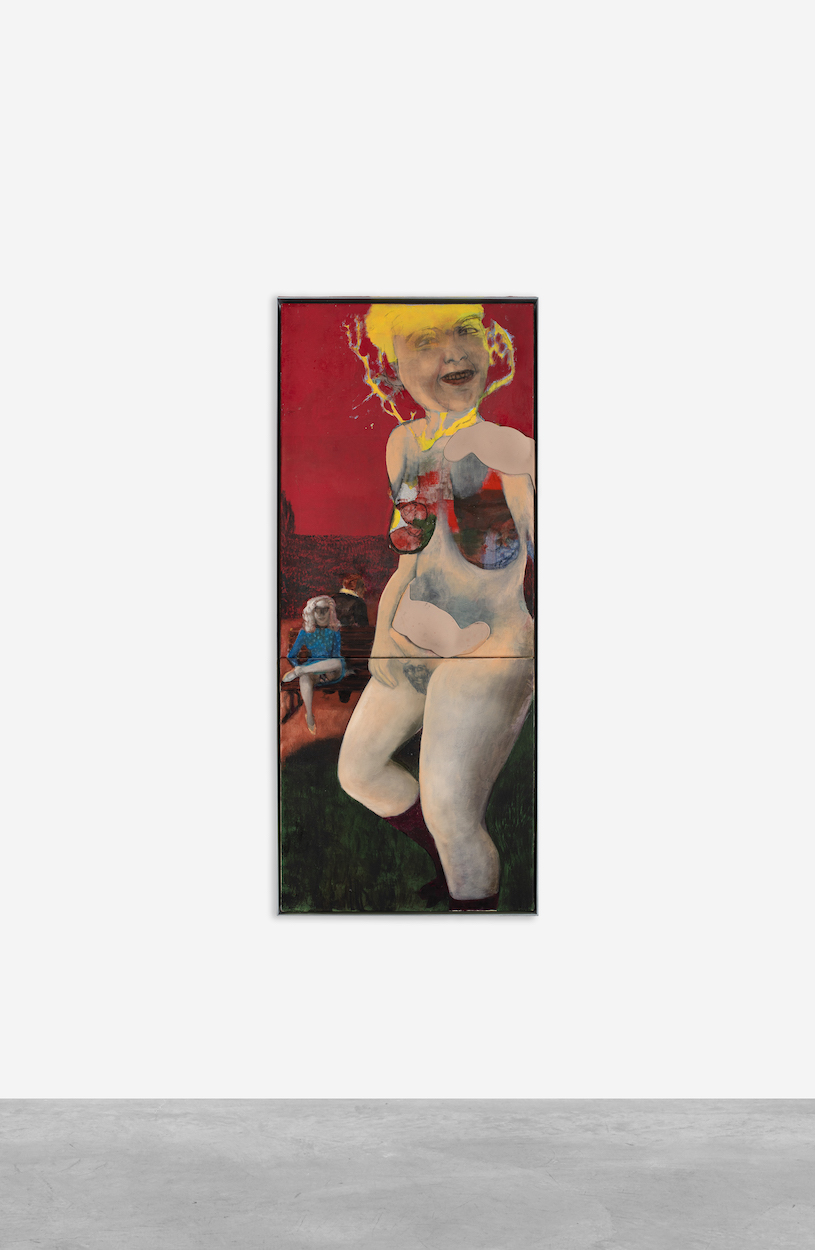

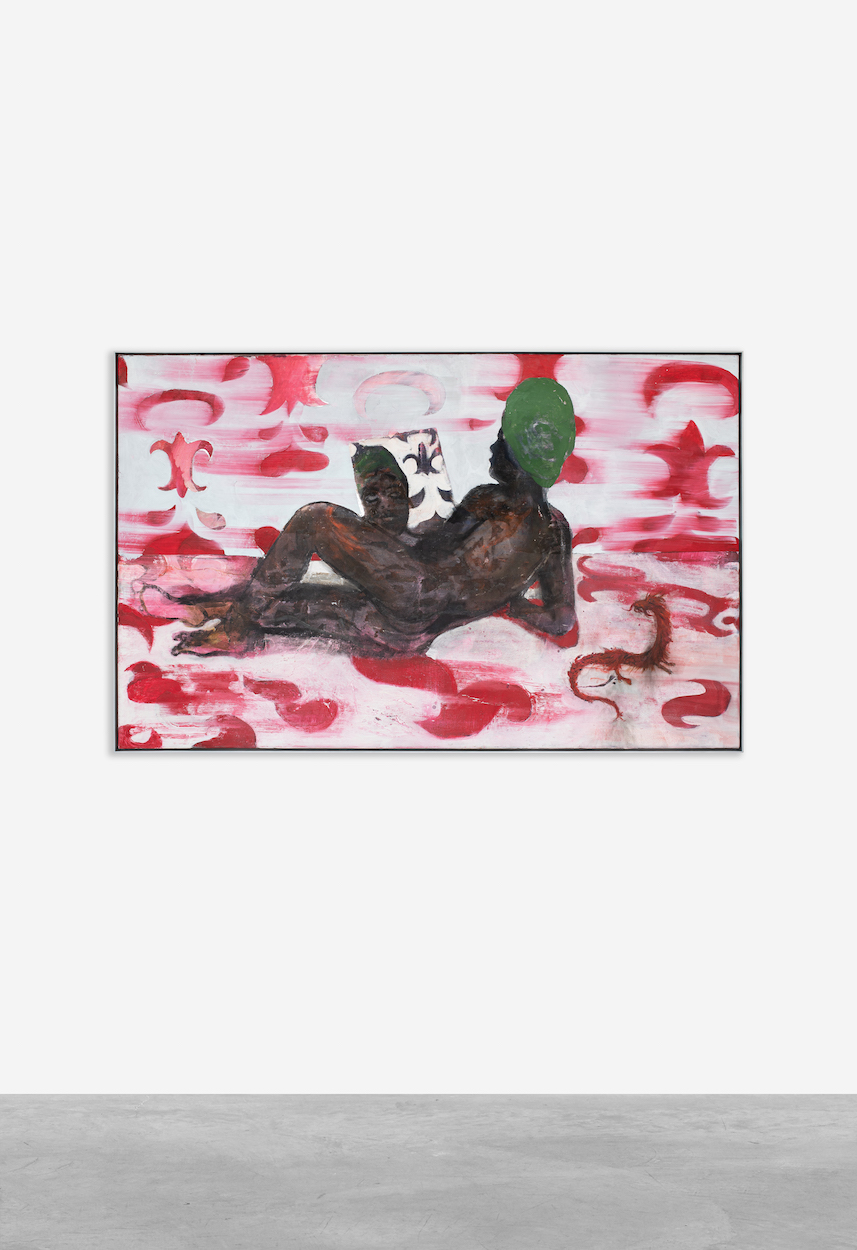

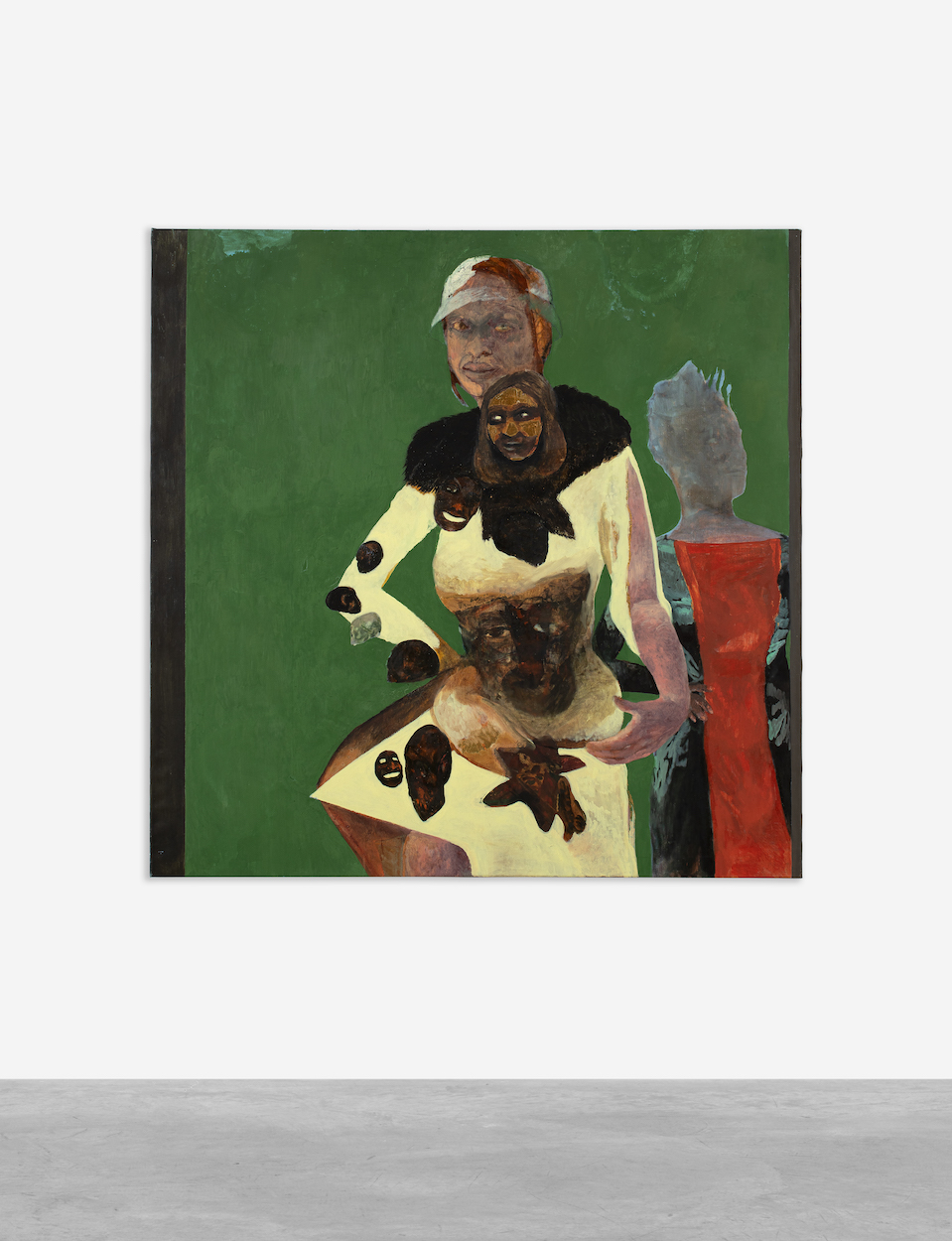

I worked on the paintings for years and most of them left my studio years ago. I saw them as fixed signs, each image selected had to feel rooted for the exhibition. The challenge was to create a grotesque space where each permanent image had its place and its sovereignty. But through this sovereignty, the space became a sort of gathering (of spirits). I call it my little Stonehenge. The small chambers with the windows are oriented towards the architecture of a hive. I did not pursue singular interests. It was always about transfiguration and transformation.

The grotesque puts you off, repels you and disgusts you, perhaps because it is so unfamiliar. It is a pure novelty. With familiar elements in it. But on the other hand, it’s a very good metaphor for painting because it becomes something that seems new but it’s composed of older, other things. The spectrum between things such as fakeness and lies and originality and truth and the recurring theme of being conceived artificially, like Frankenstein, would describe it as I perceive it.

However in painting it makes sense to show these states “stress, mental health, fluid sexualities” since words mostly fail in these situations.

Grotto suggests a cave used for intimate entertainment and loosening morals. Grotesque on the other side is something wrong or odd to a shocking degree. The word was first used of paintings found on the walls of subterranean vaults of ruins in Rome that were called “le grotte”- meaning the caves – which have become buried and overgrown until they were broken into again from above. Grotesques retrospectively depict types of decorative patterns using curving foliage elements and later half-human thumbnail vignettes drawn in the margins. People knew how they looked but didn’t quite know what they were depicting. Rémi Astruc has argued that the three main tropes of the grotesque are doubleness, hybridity and metamorphosis. In my personal world the submerged “bacchanal” atmosphere of grotto seemed like an terace to let these weird flowers of modern duality and fluidity grow. It’s an old method to use historical reference, parabolas, or past events to point out something about the present. I work with these anachronisms in a targeted way to indirectly make aspects of the present more apparent.

Often themes are circulating around mental tension and stress, taken from the “real modern life”. We don’t talk about it, thus it being so common.

Everything changes, is put on display, and pretends to be something it may not be. I found out that that’s what interests me, this element of travesty. People often perceive it as fluid, but I cross boundaries with these images that don’t feel safe to me layer after layer to decipher them. Often themes are circulating around mental tension and stress, taken fromthe “real modern life”. We don’t talk about it, thus it being so common. However in painting it makes sense to show these states since words mostly fail in these situations. It’s not a criticism, it’s just an observation. It’s so hard to sharethis closed system that each of us is.

It’s a very overstimulated time that I find myself in, so it’s good to be spiritual, putting more attention to whatever that means. I’m not trying to use it in an esoteric way, but focusing on the things of the spirit gives me hope, because the numbing is just everywhere.

I wouldn’t say I practice it, but I try to think and feel about things in a manner disattached to the dreams we get sold through consuming, apps, modern politics,journalism and medical management. Often there is decay and rotting parts of the body in my paintings. That decay and the debris I’ve worked through the years becomes spiritual to me because it was not produced in a preconceived method. I wouldn’t say I’m a spiritual painter, but I try to paint spiritual matters. I don’t believe the machine age gives full satisfaction in a spiritual way, if the term may be allowed.

I’m generally interested in all forms of sexuality as a way to lend my paintings agency. I think people quickly jump to associating my work with the gender/racially/age fluid manifesting because they sense that it might be in line with the kind of “style” contemporary painters of my generation often demonstrate, which is very much about empowering the body. In a way what I do is drilling closer to the inside than trying to empower the viewer. At best, my paintings are epiphanies. It’s always brewing for me. Layer after layer images start to appear.

I wouldn’t say I’m a spiritual painter, but I try to paint spiritual matters.

I’m trying to deal with the real, but the real can’t be truly expressed in a unified way. Even with paintings, it’s a difficult thing. So let’s say sexuality is real.

Everyone has it. But it’s not visible. And the task of the painter is to reveal whatever it is. It’s not revealing the truth, it’s revealing something that we share in hiding.

What I look for is something that I can’t explain. It has to be so everyday. Often, these “talismans“ have an organic life. Like the very crispy, freshly fried egg or the hair that grew up on the head of someone I loved or the flowers I collected. By using these materials, I’m trying to remind myself of memories and the fleetingness of life because the paintings I do, are the most important things in my life. I fill my paintings with very personal objects. Anyhow, anyway I remain very detached and observe them on the canvas. It’s reminds me of a Petri dish. Then there are the tricks I observed other painters to use, dead or alive. Then there are things that are stuck in my head that I reproduce. From movies, photos, my observations. Everything I do is painting. Painting is everything I do.

I fill my paintings with very personal objects.

Not all of them take years; most of them do. I wait so long until they’re finished because this feeling that there’s another presence looking back at me is what I’m primarily expressing. And when I reach this point, it’s finished because it’s not my work anymore. It becomes an independent object, image or illusion.

I think painting is such an old medium, but what still works for me in it is that it’s a spiritual photograph of life. I’ve developed a sense of when to push the button in my brain and hands and belly. And that happens sometimes in years, sometimes in hours. The moment is quick, and I have to focus to forget everything else. To feel when it comes alive. Then it’s no longer “my” work, even if it’s 2000% me.

The ritual is to do it every day, I barely take a day off. I think that painters – or anyone doing anything creative – should sacrifice everything for their work.

You have to search for that thing. I don’t see painting as a profession. It is a vocation, like being a doctor or a teacher.I must get as much as I witness in life back to painting or to the studio.

What interests me when I look at paintings is when I feel that the author is showing me life.

Yes. What interests me when I look at paintings is when I feel that the author is showing me life.

Right now I’m working on my show for Antenna Space in Shanghai. It’s the first time I’m showing to viewers that I dont have an image for. Whatever I said before, I analyze everything all the time and I have control issues that I creatively use in my work. It’s a balancing act, like walking a thin rope into the shadow.

Furthermore, I’m interested in painting animals right now. When I was a teenager, Rosa Bonheur used to be an idol of mine. She was this lesbian, aristocratic girl from a good house in France. She painted animals, traveled in times when there were no trains and coaches, and was a best-selling painter of the 19th century. I think about her a lot when I’m creating my works for Shanghai because of her fierceness.

I like to observe people. And not to judge but rather to get possessed by entities that I don’t know.

I don’t worry too much about it, but I have intuitions or instances. And I am concerned. Not that people will hate it or like it or be scared by it. But the viewer is the artist’s best friend and best enemy. To sense that it works inside of others is very exciting. I like to observe people. And not to judge but rather to get possessed by entities that I don’t know. I’malso looking forward to going to China in these weird times post Covid.

The show will open in May and right now, it’s just finishing the very big and very small works. Some of them I had in the studio for years. It’s like everything is dying and coming into life at the same second. Incredible.

The exhibition is open until February 5th, 2023.

All photos Courtesy of Peres Projects

Photographer: Installs by Johannes Stol / portraits by Marina Faust

Sophie Thatcher, best known for her role in the critically acclaimed series…

Photography by Jason Renaud; Interview by Louise Garier

FOTOGRAFISKA X LML Adina Bier, the curator and innovative force behind the museum…

Photography by Sascha Rebrikov Interview by Louise Garier

"We have to create something that has a purpose and is useful. And not forced by the…

Interview Carolin Desiree Becker